MRI radiomics could have a tremendous impact on the lives of patients with brain tumors, with advances bringing the concept of virtual biopsies closer to practice, according to a presentation at the annual meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM).

In a plenary session May 11 that included a tribute in memoriam of Richard Ernst, PhD, Dr. Marion Smits, chief of neuroradiology at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, discussed the promise of MRI radiomics in improving the diagnosis of brain tumors before patients undergo surgery.

"If you look at it, we're still in the 17th century -- we still need to open the skull, we still need to open the body, we need to be invasive to make a diagnosis and to continue with our treatments," Smits said.

The ISMRM held last week's meeting in conjunction with the European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology and the International Society for MR Radiographers and Technologists.

A new revolution in patient care?

Radiomics is a quantitative technique that boosts what clinicians can learn from existing clinical MRI scans using artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. Through mathematical extraction of the spatial distribution of signal intensities and pixel interrelationships, radiomics quantifies textural information.

When combined with existing clinical data on brain MRI scans, radiomics thus can provide diagnostic information on tumors on a level that researchers suggest may one day replace invasive tissue biopsies, Smits said.

"[Virtual biopsies] would give us, because it's noninvasive, the opportunity to sample the tumor not just once when we do the surgery, but at any given time point during the disease course," she said.

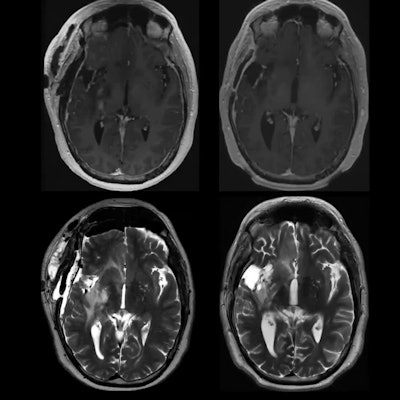

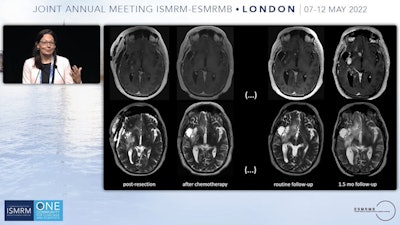

Smits provided an example of the type of patient who could benefit. She showed brain MRI scans of a patient whose tumor was resected, with no significant findings after chemotherapy. However, on a routine follow-up T2-weighted abnormalities appeared to increase, and a month later, another exam revealed the tumor had fully returned. Something happened to the tumor that made it nonresponsive to treatment, Smits said.

"We would like to know what changed because then of course we can adapt the treatments, and we won't be taking a tissue sample every time we follow these patients up," Smits said.

Importantly, the implications for patients are significant. Smits shared the comments of a young woman who writes a blog (thelizarmy.com) about her experiences having a brain tumor.

"I am having neurosurgery AGAIN," the woman wrote. "Depending on what we learn from tissue obtained during surgery, we will move into the next phase of cancer treatment."

Even after her surgery, it could take several weeks for the results of the tissue biopsy to come back for a prognosis, and this waiting and uncertainty can be mentally and emotionally traumatic, Smits said.

"We can change that," she said.

Challenges in MRI radiomics and developing virtual biopsies include acquiring quality data to feed the machine-learning algorithms. Even with MRI radiomics showing accuracies in brain tumor diagnosis between 80% and 90% in some studies, that's not good enough to be used in clinical practice to replace the gold standard of histopathological or molecular examination, Smits said.

Large datasets have been collected retrospectively and are available for research, but the problem is that, generally, they include only conventional imaging data, such as T1- and T2-weighted images, rather than more advanced imaging.

To that end, Smits concluded her presentation with a call for researchers to conduct these studies and to share the data in the field.

"I believe we are on the brink of a new revolution, but we do need to make that happen together," she said.

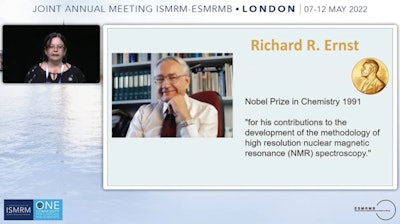

The importance of advances in MRI research and their impact on patient care was echoed in a tribute during the session to Swiss physical chemist Richard Ernst, PhD, who died last June at the age of 87. He received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1991 for his work developing high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Ernst was an exceptional scientist, inspirational lecturer, an outstanding teacher, and a man with extraordinary human qualities, said Dr. Rita Schmidt of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, who gave the presentation.

The plenary session was titled "Scientists as 'Toolmakers' in NMR & MRI" in tribute to Ernst, who called himself a "toolmaker" who "wanted to provide other people these capabilities of solving problems," Schmidt said.