A Cochrane update evaluating radiation therapy for stage I endometrial cancer patients has again concluded that the treatment doesn't affect survival outcomes. But its findings, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, sparked some controversy.

The controversy about the recommended use of adjuvant radiation therapy for stage I endometrial cancer after a hysterectomy is focused on high-intermediate-risk and high-risk women. Even with the addition of findings from four clinical trials, doubling the number included in the original Cochrane Review meta-analysis published in 2007, the number of high-risk patients remained small.

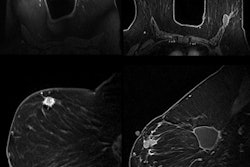

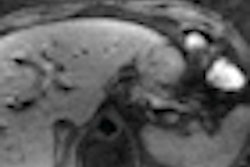

The updated meta-analysis does not dispute that external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) does reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence across all risk categories of patients. But is the treatment worth the trade-off of potentially debilitating acute and/or late toxicities and long-term complications that could reduce quality of life?

Lead author Anthony Kong, PhD, from Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, and co-authors think not. In their original analysis and in the update, they determined that EBRT had no statistically significant effect on cancer-related death or overall survival. The update reinforced the high risk of patients developing significant morbidities and experiencing reduced quality of life after receiving this treatment (JNCI, November 7, 2012, Vol. 104:21, pp. 1625-1634).

The update evaluated eight clinical trials. Seven of the trials, representing a combined patient cohort of 3,628 women, compared outcomes of patients who received EBRT versus either no radiation therapy or vaginal brachytherapy. One trial with 645 participants compared outcomes of patients who received no treatment or vaginal brachytherapy.

The patients were categorized as intermediate risk if they had stage IC (cancer has invaded more than half of the muscle wall of the uterus) or grade 3 cancer, and they were considered high risk if they were stage IC and grade 3. Women categorized as high intermediate risk were 70 or older with one additional risk factor as defined in the various clinical trials, 50 or older with two additional risk factors, or any age with three additional risk factors.

The use of EBRT among low-risk women, a treatment that has been discontinued, actually increased the risk of endometrial-cancer-related death. There was insufficient evidence to assess the value of vaginal brachytherapy, but it has been recommended as the adjuvant treatment of choice for women with intermediate-risk or high-intermediate-risk endometrial carcinoma, Kong and colleagues noted.

Although this analysis did not demonstrate a survival advantage for high-intermediate-risk and high-risk women, the authors explained that the clinical trials may not have had enough participants in these subgroups.

Dr. Patricia Eifel, professor of radiation oncology at MD Anderson Cancer Center, strongly agreed in an editorial published in the same JNCI issue (pp. 1615-1616). Noting that the annual death rate from endometrial cancer is about three per 100,000 women in Europe and five per 100,000 women in the U.S., she pointed out that the patient cohort size of women at the highest risk levels was too small.

"The high-intermediate-risk patients who had the most to gain from adjuvant treatment were barely represented in the contributing trials," she wrote. In addition, the validity of the subset analysis of different risk groups was severely compromised because, in her opinion, the estimates of risk were flawed in many of the original trials.

"Only focused trials in patients with well-characterized high-intermediate-risk tumors can provide the answer to the question that we have been trying but have failed to answer for more than 30 years," Eifel's editorial concluded.