LAS VEGAS - Musculoskeletal ultrasound has had a turbulent history, with periods of overutilization and turf battles that continue to this day. But the modality continues to flourish thanks to collaboration, according to a presentation at the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) annual meeting.

It has taken collaboration between institutions, physicians of different specialties, sonographers, and national and international organizations, according to Dr. Levon Nazarian, a professor of radiology at Thomas Jefferson University (TJU).

"The ultimate [beneficiary], which we can never forget about, is the patient," Nazarian said. "We had to come out of our silos in order to help patients, and that is really the bottom line of why we're in the medical field."

He discussed the evolution of musculoskeletal ultrasound during the 2014 William J. Fry Memorial Lecture at AIUM 2014. To demonstrate how far musculoskeletal ultrasound has grown, Nazarian shared some stories from his own personal journey with the modality. After being encouraged by his mentor Dr. Barry Goldberg to attend the 1993 Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Society meeting in Florida, Nazarian elected to learn this new area of ultrasound.

Early adopters were excited about the potential and clinical benefits of the modality. Nazarian pointed to a paper he published in the American Journal of Roentgenology six years ago (June 2008, Vol. 190:6, pp. 1621-1626), which offered 10 reasons why musculoskeletal ultrasound was an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI:

- Everyone can undergo an ultrasound

- Ultrasound can resolve finer details than MRI

- Ultrasound allows real-time dynamic examination

- The ultrasound probe can be placed exactly where it hurts

- Ultrasound can effectively image patients with surgical hardware

- Doppler ultrasound gives important physiologic information

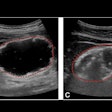

- Ultrasound is better than MRI for distinguishing cystic from solid material

- Ultrasound is better for guiding therapeutic interventions

- Ultrasound facilitates bilateral comparison

- Ultrasound has a more flexible field-of-view

As part of his personal learning curve, Nazarian scanned both normal and abnormal volunteers and also dispensed free ultrasound scans to patients getting MRI studies.

"When I got to a certain level when ultrasound started disagreeing with the MRI and the ultrasound was right, that's when I stopped doing comparisons with the MRI," he said.

Nazarian also performed clinical research and gradually began to offer musculoskeletal ultrasound as a clinical service. Between 1993 and 1997, the depth and breadth of TJU's musculoskeletal ultrasound program grew in both the clinical and research arenas. The university also began marketing the service to referring physicians and also trained sonographers, Nazarian said.

Questioning musculoskeletal ultrasound

The modality hit a big roadblock in the 1990s, however. Paraspinal ultrasound had become a $35 to $40 million business in the U.S., typically for the evaluation of whiplash injuries. Some concerns had been raised, though, about the validity of this type of imaging study.

Thanks to the impetus of Dr. Barry Bakst, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician in the Philadelphia area, Nazarian and colleagues performed a study that found that paraspinal ultrasound suffered from a lack of accuracy in evaluating patients with cervical or lumbar back pain (Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, February 1998, Vol. 17:2, pp. 117-122). Nazarian later participated in an FBI investigation into a New York practice that had been performing $20 million worth of paraspinal ultrasound studies per year, which resulted in jail time for a few of the participants.

"This experience got me to realize that we really have to take care of [musculoskeletal ultrasound], and make sure that we're making this field valid for it to go forward," Nazarian said.

Recognizing a need for education, TJU held its inaugural musculoskeletal ultrasound course at the Jefferson Ultrasound Research and Education Institute. The course had an excellent turnout, with attendees including physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, nonoperative sports medicine physicians, rheumatologists, orthopedic surgeons, and chiropractors.

"But there were very few radiologists, and this surprised me," Nazarian said.

Lack of interest by radiologists

The hesitancy of radiologists to learn musculoskeletal ultrasound was a second roadblock to the modality's growth. Radiologists were reluctant to learn musculoskeletal ultrasound due to concerns that it was too operator- and equipment-dependent, he said. In addition, the modality has a long learning curve.

"Sonographers may be insecure with anatomy and pathology, and musculoskeletal radiologists may be insecure with ultrasound," he said.

Referring physicians are also more comfortable with MRI, and there is much higher reimbursement for MRI.

The general imaging paradigm should be to do the less expensive test first and save the most expensive test for when it's indicated, such as what occurs with pelvic ultrasound and pelvic MRI. However, in musculoskeletal imaging, MRI is done first, with ultrasound performed only if indicated, Nazarian said.

"This is backwards, and it's so obvious that it's backwards," he said. "But it takes a while to get people to buy in to the fact that we need to change what we're doing."

To encourage more radiologists to participate in musculoskeletal ultrasound, there was an attempt to get a CPT code for shoulder ultrasound. However, this proposal was denied by the American College of Radiology's Economics Committee, which felt that it would take money from other CPT codes and encourage nonradiologists to use ultrasound, Nazarian said.

Who should do MSK ultrasound?

There have been a number of arguments as to why musculoskeletal ultrasound should be performed by radiologists. For example, radiologists have the most formal ultrasound training and are better suited to perform correlative imaging if necessary, Nazarian said.

There is also less chance for self-referral, which reduces overutilization and medical costs, he said.

On the flip side, there are also compelling reasons why musculoskeletal ultrasound should be performed by nonradiologist physicians. For example, it's convenient for the patient to receive a clinical evaluation and imaging in one visit.

In addition, ultrasound by nonradiologists could reduce the need for costly MRI studies and provide guidance for interventions. This paradigm also supports portability, enabling physicians to bring ultrasound to athletic fields and other points of care.

A compromise position would be to have clinicians running ultrasound scanners in their offices. In the majority of cases, clinicians can scan and read the musculoskeletal ultrasound studies themselves. But if they can't answer the clinical question, they would then refer the patient to the radiologist, who has more experience and higher-end equipment, Nazarian said.

"It's not either/or; there can definitely be a middle ground," he said.

Saving money for insurance companies

To spur more utilization, TJU researchers sought to evaluate the cost savings from the prudent substitution of musculoskeletal ultrasound for MRI. In research published in 2008 (Journal of the American College of Radiology, March 2008, Vol. 5:3, pp. 182-188), the study team estimated 15-year Medicare savings of $6.9 billion in the U.S.

"We thought it was implicit that the payors may stop paying for MRI for certain indications," he said. "And after several years, we're starting to see this happen."

Another roadblock along the way was the lack of sonographer training in musculoskeletal ultrasound, Nazarian said.

This has been addressed by courses, Web-based teaching materials, anatomy books, and on-the-job training via physician and sonographer collaboration. The Registered in Musculoskeletal (RMSK) credential was established in 2012 by the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography (ARDMS), providing an added incentive for sonographers to learn.

Intraspecialty collaboration

Another important driver of musculoskeletal ultrasound has been collaboration between different specialties at the same institution, such as what took place between the sports medicine and radiology departments at TJU. This teamwork was triggered with a call to Nazarian from Dr. John McShane, then a sports medicine physician at TJU.

McShane wanted to convert arthroscopically assisted surgery to ultrasound-guided surgery, and he worked with Nazarian to develop techniques and instruments specifically for repairing injuries.

"Over 10 years, McShane devised and I provided ultrasound guidance for minimally invasive treatments for tennis elbow, plantar fasciitis, jumper's knee, Achilles tendinosis, trigger finger, and carpal tunnel syndrome," Nazarian said. "It was an incredible time of learning and pushing the field forward."

Payor problems

Yet another obstacle in the path of musculoskeletal ultrasound was that payors started to deny payments for the scans in 2009. This came amidst research by TJU that documented dramatically increased musculoskeletal ultrasound utilization from 2000 to 2009, especially by podiatrists.

In 2009, Blue Cross/Blue Shield (BCBS) announced it would deny payment for all musculoskeletal ultrasound (CPT code 76880) across the board in Texas, Illinois, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.

"The policy cited musculoskeletal ultrasound as 'experimental,' and the irony is, they cited my own paper [on paraspinal ultrasound] to justify this conclusion!" Nazarian said.

BCBS also mentioned other reasons, such as the proliferation of diagnostic ultrasound units, and its use by individuals without proper training and under conditions of inadequate control.

Although the policy was reversed after a campaign of letter writing, phone calls, etc., it became clear there was a need for sensible policies on the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound, Nazarian said.

"Unless we curtail collective overutilization, the plug could be pulled again," he said. "We can't assume this is over, and we have to continue to keep our standards high to control overutilization."

A diverse and multispecialty organization, AIUM was a natural choice to shepherd the modality, according to Nazarian. A Musculoskeletal Community of Practice was launched in 2002. In addition, AIUM has promulgated practice guidelines, training guidelines, accreditation, and courses.

"Collaboration, not competition, has allowed musculoskeletal ultrasound to flourish," he said.