Combining blood tests with sonography findings significantly outperformed ultrasound alone for diagnosing or ruling out pediatric appendicitis, and the combination could also reduce the number of CT scans in children, according to research published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective study of 845 children seen in the emergency department between 2010 and 2012 for suspected appendicitis, researchers from Boston Children's Hospital found that 51% of ultrasound studies were considered to be equivocal. However, the use of blood test data -- specifically, white blood cell (WBC) count and polymorphonuclear leukocyte differential (PMN%) -- increased negative predictive value (NPV) from 41.9% to 95.8% in these patients, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001).

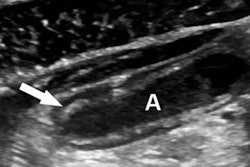

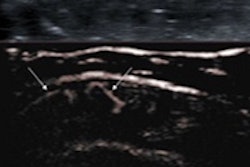

In the 18% of patients who had only primary signs of appendicitis on ultrasound, such as increased blood flow or thickening of the appendix wall, the risk of appendicitis increased from 79.1% to 91.3% when the lab studies indicated a bacterial infection. In the 24% of patients who had only secondary signs of appendicitis, such as fat near the appendix, the appendicitis risk climbed from 89.1% to 96.8% when laboratory results were abnormal (JACS, January 30, 2015).

Notably, the researchers said that using the tests could obviate the need for CT. Following guidelines recommending against the use of CT for very high-risk and low-risk categories based on combined ultrasound and laboratory data would have avoided 101 (27.1%) of the 373 CT exams performed during the study period.

"Although our results reflect the experience of a single freestanding children's hospital, the conceptual approach described in this study for characterizing predictive profiles on the basis of laboratory and sonographic data is likely to be generalizable to many, if not all, hospitals that treat appendicitis in the pediatric population," said senior author and pediatric surgeon Dr. Shawn Rangel.

However, instead of suggesting that other institutions adopt their sonographic categories or lab value thresholds for pediatric appendicitis, the researchers advocate that hospitals work with their own radiologists and emergency department physicians to develop a customized approach for categorizing sonographic findings. They should then "develop risk profiles that are tailor-made for their patients after incorporation of their institution's laboratory data," he said in a statement.

"Institutions can use the risk profiles as educational vehicles and clinical guideline decision tools to help emergency department physicians and surgeons avoid unnecessary [CT] scans and admissions for observation for very low-risk patients, and avoid treatment delays in very high-risk patients," Rangel said.