Despite stable mortality rates over time, the incidence of thyroid cancer has skyrocketed in Canada -- particularly among middle-aged women and in certain provinces. The culprit for this "overdiagnosis epidemic" is diagnostic imaging, according to a study published online in CMAJ Open.

Researchers from the University of Calgary reviewed thyroid cancer incidence data in Canada from 1970 to 2012 and found a rapid increase in diagnosed thyroid cancers after 1990. What's more, they found significant variation in incidence rates among the provinces.

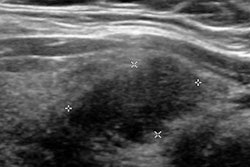

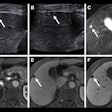

These increases and regional variations were tied to higher imaging utilization, especially for ultrasound of the neck. Mortality rates, however, have remained stable despite no change in thyroid cancer treatment protocols over the study period.

"The likely cause of the increase in incidence is an overdiagnosis epidemic for clinically unimportant lesions detected by modern diagnostic imaging," wrote authors Dr. Dawnelle Topstad and James Dickinson, PhD. "To reduce the harms of overtreatment, overdiagnosis should be reduced, through more judicious use of diagnostic imaging."

More cancers found

As in many other high-income countries, thyroid cancer incidence rates have grown rapidly over the past few decades in Canada. Most of these newly diagnosed cancers are papillary thyroid carcinomas, which typically have an indolent course, according to the researchers.

"There is thus the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment of lesions that if left alone would never cause any problems," the authors wrote. "Choosing Wisely Canada has indicated that the early detection of small thyroid lesions contributes to overdiagnosis and suggests limiting use of thyroid ultrasound."

Practice patterns differ between provinces in Canada, so the researchers sought to assess how thyroid cancer incidence has changed in the country and how it varies between the provinces. They searched the National Cancer Incidence Reporting System, causes of death tables, and the Canadian Cancer Registry using the 1991 census population structure (CMAJ Open, August 14, 2017).

Topstad and Dickinson found that thyroid cancer incidence rates in Canada increased nearly sixfold for women and nearly fivefold for men from 1970 to 2012.

| Thyroid cancer incidence rates in Canada | |||||

| 1970 | 2012 | ||||

| Women | 3.9 per 100,000 | 23.4 per 100,000 | |||

| Men | 1.5 per 100,000 | 7.2 per 100,000 | |||

Delving further into the data, the researchers found that the thyroid cancer incidence rates for men barely changed from 1972 to 1992. Incidence rates doubled for women over that time frame, however, starting from about age 30.

Growth accelerated from 1992 to 2012; incidence rates began to rise in the teenage years for women and increased rapidly through young adulthood -- peaking at a rate of 43 per 100,000 between 40 and 60 years of age. Rates then dropped steadily at older age, according to the researchers.

Incidence rates also rose steadily for men until age 80, but they were much higher at all ages in 2012 compared with 1992. The initial rise was seen for men in their 20s.

Regional variation

Ontario had the highest incidence of thyroid cancer for both women (31.2 per 100,000) and men (9.2 per 100,000) in 2012. The province also had the highest age-specific incidence rate; women in Ontario ages 50 to 54 had an incidence rate of 65.2 per 100,000. The lowest overall incidence was found in British Columbia, with a rate of 13.2 per 100,000 for women and 4.5 per 100,000 for men. The variation between the provinces and increase in thyroid cancer incidence does not correspond to any known cause or risk factor for the disease, according to the researchers.

While the numbers were too small to calculate age-standardized mortality rates by sex, crude mortality rates were stable over the study period, varying from 0.42 to 0.8 per 100,000 in women and 0.16 to 0.59 per 100,000 in men, according to the authors. Most of the women and men who died were older than 60 years of age.

Thyroid cancer treatment is identical for women and men, so it is unlikely that more effective treatment explains the stable mortality rates, they noted.

"The most likely explanation is that a consistent small number of potentially lethal thyroid cancers develop and may be ameliorated by the treatments, while many currently detected thyroid cancers either would not progress if untreated or would develop very slowly with minimal risk," the authors wrote.

Differences in practice

The variation in thyroid cancer incidence rates among the provinces and the changes in age-specific incidence are likely due to varying rates of overdiagnosis caused by differences in practice, according to the researchers. For example, use of ultrasound, CT, and MRI climbed 18% in Ontario, with women younger than 60 receiving three times more diagnostic imaging than men.

"This increasing use of imaging is mirrored by the increasing rates of thyroid cancer diagnosis, with the fourfold variation in diagnostic rates between regions correlating with patterns in the use of ultrasound, especially of the neck," the authors wrote.

A previous study found that the increase of thyroid cancer in Ontario was mainly due to small differentiated tumors; also, the greatest increase was in tumors smaller than 2 cm, which are considered nonpalpable and subclinical.

"These findings support the hypothesis that the increased incidence rates of thyroid cancer are due to overdiagnosis, with cases discovered incidentally in small tumors," Topstad and Dickinson wrote.

The study results also reinforce Choosing Wisely Canada's recommendation not to order thyroid ultrasound routinely in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests unless there is a palpable abnormality of the thyroid gland, they added.

"Further effort should concentrate on reducing overuse of diagnostic imaging and finding better ways to distinguish those patients with unimportant indolent tumors, while still identifying aggressive thyroid cancer that needs treatment," they wrote.