Ultrasound is a reliable alternative to MRI for assessing liver steatosis in the clinical setting, according to a study published in the July issue of Clinical Radiology. The findings offer clinicians a cost-effective, accessible option for evaluating steatosis.

While MRI has become an accepted modality for detecting liver steatosis, it comes with a high cost and is generally less available than other modalities, according to a team led by Dr. Marie-Luise Kromrey of University Medicine Greifswald in Germany. "Ultrasonography is commonly used to detect liver steatosis and has the advantage of being cost-effective, simple, and widely available," the team wrote.

Fat storage in the liver can be an indicator of metabolic syndrome, a condition characterized by insulin resistance and a precursor to type 2 diabetes. Since liver steatosis is also a risk factor for a variety of other diseases, having an effective way to assess it is important, Kromrey and colleagues noted.

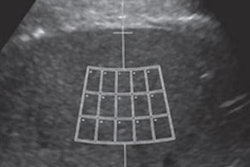

Yet although ultrasound is regularly used to detect liver steatosis, its diagnostic accuracy and reliability for assessing the severity of fatty liver have been unclear. So Kromrey and colleagues conducted a study to compare the modality's performance to that of MRI.

The study included 2,783 patients who underwent 1.5-tesla MRI scans of the liver; from these MRI exams, the group calculated proton-density fat fraction and transverse relaxation rate to estimate liver steatosis and iron overload. Patients also underwent B-mode ultrasound. Kromrey's team then assessed the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound to identify different degrees of steatosis and amounts of liver iron (Clin Radiol, July 2019, Vol. 74:7, pp. 539-546).

MRI showed liver steatosis in 40% of participants (mild, 68.9%; moderate, 26.7%; severe, 4.4%), while ultrasound found liver steatosis in 37.8%, which corresponded to a sensitivity of 74.5% and a specificity of 86.6%.

The group also found that ultrasound sensitivity increased with the amount of liver fat present (65.1% for low fat content, 95% for moderate fat content, and 96% for high fat content). Liver iron did not affect ultrasound's ability to detect liver steatosis, Kromrey and colleagues noted.

"The present results show excellent sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for the estimation of fatty liver disease in patients with moderate and high liver fat content," the group wrote.

However, since ultrasound didn't perform as well in patients with low liver fat content, additional evaluation methods may still need to be used, according to the team.

"The weakness of ultrasound in assessing small amounts of liver fat should be considered and compensated by additional liver enzyme quantification or MRI," the authors concluded.