The answer to preventing cross-contamination from repeat use of ultrasound probes may not come in the form of extensive cleaning or antibacterial chemicals but rather a simple strip of adhesive tape.

That's what a team led by Yuan Qin, PhD, from the Beijing University of Chemical Technology found in a study published October 6 in Surfaces and Interfaces.

The researchers say using acrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) tape as an ultrasound probe cover not only prevents cross-infection but also has less impact on the clarity of ultrasound images and saves time for radiologists.

"The ease of preparation, convenience of use, and effectiveness of acrylate PSA tapes indicate that they have broad application prospects for sonographic examinations," Qin and colleagues wrote.

Ultrasound probes are an essential part of medical ultrasound imaging. The most commonly used cleaning methods include using paper towels to wipe out coupling gel and chemically treating probes with alcohol or quaternary ammonium compounds. However, researchers said damages to the probes and cross-infection between patients might be unavoidable.

Radiologists should also eliminate ultrasound transmission gel on the probes after scanning. However, researchers said this is a time-consuming process.

"Nowadays, how to improve convenience and how to reduce the time between examinations are important issues to be considered because ultrasound diagnosis is required quickly and effectively in the face of many patients," Qin et al wrote.

Acrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive tape is already used for medical applications such as wound coverings and transdermal drug delivery systems. The researchers touted its nontoxic, transparent, and mechanical properties, as well as its tendency to leave no residue behind.

The team wanted to test the effectiveness and feasibility of pressure-sensitive adhesive tape on preventing cross-contamination and improving productivity.

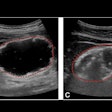

Probes were used on a skin-like silicone puncture phantom that simulated human tissue. Three types of glue were used for the tapes, and air bubbles were rolled out as the tapes were added to the probes. The glues include Polyethylene terephthalate, polyurethane, and polyethylene.

Polyethylene film with good softness, little effect on the clarity of ultrasonic images, and substrate versatility, was selected as the underlying layer of film for the tapes.

Results showed that the shear strength of tapes improved with increasing molecular weight of acrylate copolymer. However, tack and 180° peel strength showed a downward trend.

Forming a cross-linked network among polymer chains also greatly improved the shear strength of tapes to meet the requirements of ultrasound probe covers, including being easy to peel from the ultrasound probe, easy to adhere to the probe, not leaving residue behind, and having less impact on the clarity of ultrasound images.

The researchers also found that a viscoelastic adhesive layer of tape can replace the coupling gel between ultrasound probe and pressure-sensitive adhesive tape.

A clinician judged the quality of images taken with the taped probes and said tape containing polyethylene and polyurethane had "excellent" image clarity, as well as "excellent" softness for contact with human skin.

The study authors said that compared with conventional disinfecting procedures, pressure-sensitive adhesive tape for probes has three advantages. They included preventing direct contact with the human body to reduce cross-infection and lens degradation, minimizing downtime between patients through easy tape adherence and removal, and replacing the coupling gel, which could help avoid paper towel usage and minimize cross-infection risk.

They added that it could also reduce the occurrence probability of corrosion and electric leakage.

"[The tape] is expected to find applications in sonographic examinations in the future to protect ultrasound probes and to prevent cross-infections," Qin and colleagues wrote.