Focused ultrasound could help ease pain by manipulating the area of the brain that registers pain, a proof-of-principle study published February 1 in Pain found.

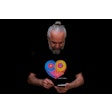

Researchers led by Wynn Legon, PhD, from the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC (Virginia Tech Carilion) found that low-intensity focused ultrasound can nonsurgically modulate the anterior insula and posterior insula in humans, with participants reporting lower pain levels after undergoing procedures.

“Taken together, low-intensity focused ultrasound is an effective noninvasive method to individually target subregions of the insula in humans for site-specific effects on brain biomarkers of pain processing and autonomic reactivity that translates to reduced perceived pain to a transient heat stimulus,” Legon and co-authors wrote.

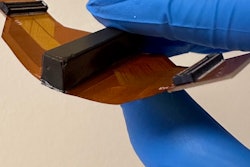

Previous research has explored the potential of noninvasive techniques to treat neural issues. Low-intensity focused ultrasound is one such method, which nondestructively and reversibly changes brain activity with high spatial resolution and adjustable depth of focus.

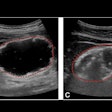

The Legon team investigated whether low-intensity focused ultrasound to either the left anterior or posterior insulae would affect the amplitude of the contact heat-evoked potential, pain ratings, or heart rate variability. The insula makes up part of the cerebral cortex and serves as a critical area of the brain for nociception and the pain experience.

The researchers included 23 healthy participants in their study. The participants had heat applied to the backs of their hands to induce pain. Simultaneously, they wore a device that delivered focused ultrasound waves to a spot in their brain guided by MRI.

The participants rated their pain perception for each heat application on a 0-to-9 scale. The researchers also observed heart rate and heart rate variability in each participant to find out how ultrasound waves delivered to the brain affect the body’s reaction to painful stimuli.

The team found that the participants reported an average pain reduction of three-fourths of a point. It added that the pain decrease was more pronounced when ultrasound waves were delivered to the posterior insula.

Legon said this difference, while seemingly small, could make a significant difference in quality of life or managing chronic pain with over-the-counter medicines instead of prescription opioids.

The researchers also reported that the use of ultrasound reduced physical responses to the stress of pain. They explained that ultrasound waves to the posterior insula affected earlier electroencephalographic amplitudes while waves to the anterior insula affected later such amplitudes.

“Only LIFU to the anterior insula affected heart rate variability as indexed by an increase in standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals and average heart rate variability low-frequency power,” the researchers wrote.

The study authors suggested that the effect of focused ultrasound on heart rate and heart rate variability may be a future research direction. This includes studying how the heart and brain influence each other and whether pain can be eased down by reducing its cardiovascular stress effects.

The full study can be found here.