While MRI provides high sensitivity for cancer detection in women at high risk of breast cancer, there is very limited evidence that the modality can influence the selection of surgical treatment or reduce the number of subsequent operations, according to a new study published in the December issue of the Lancet.

Researchers from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) reviewed studies from May 2001 to May 2011and found little data regarding longer-term outcomes, such as ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence rates and contralateral breast cancer incidence, and no clear evidence backing the benefit of MRI in terms of survival data.

Still, MRI performed better than other methods in assessing the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and "is helpful in identifying the primary tumor in patients who present with axillary adenopathy," the authors wrote (Lancet, Vol. 378:9805, pp. 1804-1811).

MRI "is a very valuable modality for screening women at high risk of breast cancer, because of family history or gene mutations. That I am not questioning," said lead study author Dr. Monica Morrow, chief of breast service at MSKCC and professor of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College. "What I am questioning is the way [MRI] has been used to date. Whether, in fact, it has any value in average women with breast cancer."

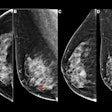

As Morrow and colleagues noted, mammography has been the modality of choice for screening women for breast cancer, and it has been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality. MRI, by comparison, offers greater sensitivity for detecting breast cancer, even for women with dense breasts. For example, one previous study found that mammography's sensitivity varied from 14% to 59%, compared with MRI, which ranged in sensitivity from 51% to 100%.

The MSKCC meta-analysis of breast cancer studies concluded mammography had sensitivity of 32%, compared with MRI's sensitivity of 75%. In addition, by combining the two modalities, sensitivity increased to 84%.

MRI's sensitivity was greater than that of mammography for detecting invasive breast cancer, which, in turn, resulted in the discovery of smaller cancers and the occurrence of fewer interval cancers.

However, the researchers found "limited evidence to support the idea that use of MRI improves patient outcomes. The strongest evidence of benefit is in screening known BRCA mutation carriers or women who have an increased risk of breast cancer because of their family history."

"There are some very special circumstances where I believe [MRI] does have value, but that is not most women with breast cancer," Morrow said "So, if MRI does not decrease the number of surgeries you are going to do -- which the evidence doesn't say it does -- and if it doesn't change the risk of local recurrence, then what is its value?"

Morrow hopes that the MSKCC study fosters "healthy debate" on the value of MRI for women with breast cancer, similar to discussions over the appropriate age for women to receive mammography screenings.

"Personally, I don't believe [MRI] has a role in the routine management of women with breast cancer right now," she told AuntMinnie.com. "If you have a clinical problem, [MRI] may be helpful in problem-solving, but that's not most women with breast cancer."

For example, the modality could help clinicians evaluate women undergoing preoperative chemotherapy, and it could also help them assess how much tumor is left afterward.

"For the garden-variety woman with breast cancer, I don't think we need MRI to appropriately select which operation to do," Morrow said. "It does not seem to help us get clear margins or decrease the number of women who start out getting a lumpectomy and end up having a mastectomy."

Morrow said future research could focus on a specific MRI application, but she added that trying to reduce local recurrence rates from 5% to 4% or 3% should not be a research priority.