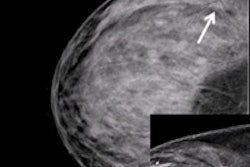

The battle over breast screening was revived yet again this week with data from a controversial Canadian study in BMJ that cast doubt on mammography's effectiveness for women ages 40 to 59. Mammography proponents quickly rose to point out flaws in the trial, which contradicts other population-based breast screening studies.

The Canadian National Breast Screening Study (CNBSS) was originally conducted in the 1980s and involved more than 89,000 women randomized to screening and control groups. Data from the trial have been released at various intervals over the years, consistently undercutting claims that mammography is an effective tool for reducing the death rate from breast cancer.

The most recent results include data from a 25-year follow-up period and confirm previous conclusions: namely, that annual screening mammography for women between the ages of 40 and 59 does not reduce breast cancer death beyond the effects of physical exams or usual care from their doctors. The researchers, led by Dr. Anthony Miller of the University of Toronto, also found high rates of overdiagnosis among women who were screened (BMJ, February 11, 2014).

Mammography advocates are repeating arguments previously made against the study: that it used questionable methodology and poor-quality mammography technique, with physicians inadequately trained to read mammograms.

Long-term follow-up

CNBSS was conducted between 1980 and 1985, and it included more than 89,000 women between the ages of 40 and 59 who were randomized into a screening group and a control group. Women in the mammography arm of the trial had a total of five annual screening exams with two-view film-screen mammography, while those in the control arm were not screened.

Women ages 40 to 49 in the mammography arm and all women 50 to 59 in both study arms received annual physical breast exams. Women ages 40 to 49 in the control arm received a single physical exam followed by usual care from their family doctor. The researchers defined the screening period as the first five years of the study, with the follow-up period spanning years 6 to 25.

During the total study time frame, 3,250 women in the mammography arm and 3,133 in the control arm were diagnosed with breast cancer, and 500 and 505, respectively, died of breast cancer. This demonstrates that the cumulative mortality from breast cancer was similar between women in the mammography arm and those in the control arm, Miller and colleagues wrote.

In addition, 22% of screen-detected breast cancers were overdiagnosed, representing one overdiagnosed breast cancer for every 424 women who received screening in the trial, according to the authors.

"Our data show that annual mammography does not result in a reduction in breast cancer-specific mortality for women aged 40 to 59 beyond that of physical examination alone or usual care in the community," the authors wrote. "The data suggest that the value of mammography screening should be reassessed."

The new findings echo a similar paper from the group in 2000, when researchers concluded that the death rates between the two groups were almost identical. At that time, the authors also suggested that annual clinical exams and breast self-examination worked just as well as mammography.

Comparison to Swedish study

Like the most recent study results, the data 14 years ago also prompted a firestorm of controversy. Detractors of the Canadian trial have compared the findings with those of other screening trials, in particular the Swedish Two-Country Trial, a landmark study that found a 31% reduction in mortality associated with screening. Other large-scale trials have also demonstrated a mortality benefit for mammography.

Miller and colleagues addressed the comparison in their current paper, pointing out that participation in the Swedish trial was based on invitation to screen, rather than actual screening. Also, in the Swedish trial, informed consent was not used, randomization was at the county level rather than the individual, and screening was performed every 24 to 33 months rather than annually.

"Too little data has been published on the Swedish Two-County Trial to confirm that the compared arms were properly balanced by the cluster randomization performed," Miller told AuntMinnie.com by email.

In an editorial also published in BMJ, Dr. Mette Kalager of the University of Oslo noted that the Canadian study "is the only trial to enroll participants in the modern era of routine adjuvant systemic treatment for breast cancer, and the women were educated in physical breast examination as advocated today."

Kalager repeated a claim made by other skeptics of breast screening: that the decline in breast cancer mortality seen in many studies after the start of mammography screening -- and also demonstrated in the Canadian trial -- is actually the result of better treatment rather than screening itself.

She concluded with a riposte against mammography proponents.

"As time goes by we do indeed need more efficient mechanisms to reconsider priorities and recommendations for mammography screening and other medical interventions," Kalager wrote. "This is not an easy task, because governments, research funders, scientists, and medical practitioners may have vested interests in continuing activities that are well-established."

Flawed data?

However, as in 2000, defenders of mammography have been quick to point out what they say are flaws in the Canadian study.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) and the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) immediately released a statement, calling the study "incredibly flawed and misleading" and based on poor-quality mammography; the Canadian study's own reference physicist said the quality of mammography was far below state of the art, ACR and SBI said.

"The results of this BMJ study, and others resulting from the CNBSS trial, should not be used to create breast cancer screening policy as this would place a great many women at increased risk of dying unnecessarily from breast cancer," the groups said.

Dr. Daniel Kopans of Massachusetts General Hospital echoed claims that the equipment used was substandard, with "secondhand" mammography machines used for screening. He also charged that patients were not properly positioned, and that radiologists had no specific training in mammography interpretation (the authors said the breast examiners received one month of training before participating in the study).

"It would be an outrage for women if access to screening was curtailed because of the poor results in the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, when it has been known for years that the trial was compromised from the start," he told AuntMinnie.com in an email. "Having been one of the experts called on in 1990 to review the quality of their mammograms, I can personally attest to the fact that the quality was poor."

Kopans believes that the Canadian researchers compromised the study data with how they selected patients for each study arm. Every woman first had a clinical breast examination, so the researchers knew the women who had breast lumps -- many of which were cancers -- and they knew who had large lymph nodes in their armpits, indicating advanced cancer.

"In order to be valid, randomized, controlled trials require that assignment of the women to the screening group or the unscreened control group is totally random," Kopans said. "A fundamental rule for randomized, controlled trials is that nothing can be known about the participants until they have been randomly assigned so that there is no risk of compromising the random allocation ... [and] a system needs to be employed so that the assignment is truly random and cannot be compromised. The CNBSS violated these fundamental rules."

Another mammography proponent, Dr. László Tabár of the University of Uppsala (and one of the co-investigators on the Swedish Two-County Trial), had harsh words for the Canadian study. Like Kopans, Tabár raised questions about the randomization process, as well as the adequacy of the training period for those reading the mammograms. He also noted that the Canadian study's findings don't match those of other large screening trials.

"The Canadian trials are the only ones among all the trials that did not report any decrease in the advanced cancer rate," Tabár told AuntMinnie.com. "This is not surprising because of the above-mentioned imbalances, but also because the radiologists were not trained for the demanding task of finding early breast cancers."

Given the controversy, is another randomized trial needed to resolve the debate over breast cancer screening? No, according to Miller. Rather, he claims that the Canadian study's results show an urgent need for policymakers to reassess the rationale behind mammography screening.

"Another trial would take too long," he told AuntMinnie.com. "Instead, we need more careful consideration of the data out there, and a recognition that mere detection of a cancer does not equate with benefit."