It's time for both sides of the mammography screening debate to drop the same old arguments and start thinking about the problem of breast cancer in new ways, according to two opinion papers published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Breast screening is only part of the "answer" to breast cancer, according to Dr. Russell Harris from the University of North Carolina. And Dr. Peter Jüni and Marcel Zwahlen, PhD, of the University of Bern in Switzerland suggest that endlessly mining data from existing trials will not produce fresh insights -- what's needed is a new breast cancer screening trial (Ann Intern Med, April 8, 2014).

Screening is not a magic bullet

We must move away from a primary focus on screening toward the larger issue of reducing the burden of suffering that breast cancer brings to society, advised Harris, an epidemiologist and internal medicine physician, in the first article. He also was a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) when its 2009 screening mammography recommendation was released.

"Breast cancer is a terrible scourge, and all of us would like to get rid of it," he told AuntMinnie.com. "But the burden it places on our society goes beyond the cancer itself to include false positives, overdiagnosis, and the general fear the disease inspires. I suggest that our attention should be drawn to addressing and reducing this overall burden."

Nearly 300,000 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer and 40,000 will die from it this year, Harris wrote. But the data doesn't show that screening is the answer: Several studies, including the recent and highly publicized update of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study (CNBSS), highlight the danger of tying all our hopes to screening as a solution for the burden of breast cancer.

Dr. Russell Harris from the University of North Carolina.

Dr. Russell Harris from the University of North Carolina.

"CNBSS was actually two randomized, controlled trials," Harris wrote. "One asked whether intensive screening with mammography and clinical breast examination (CBE) every year for four to five years reduces breast cancer deaths compared to minimal screening (one-time CBE) for women aged 40 to 49. After 25 years of follow-up, the answer was no. The other trial asked whether adding mammography to CBE reduces breast cancer deaths more than CBE alone for women aged 50 to 59 years. After 25 years of follow-up, the answer was no."

Harris acknowledged that the Canadian trial has been criticized for errors in randomization, inadequate quality of mammography, and inadequate follow-up of positive screening results. However, its strengths include individual randomization (rather than clustered), high rates of screening in the screening group, and long-term follow-up.

Some of the Canadian trial's findings differ from what USPSTF discovered when it conducted its meta-analysis for the 2009 recommendation, according to Harris. Trials performed in the 1970s and 1980s showed that mammography resulted in a 15% relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality for women ages 40 to 49 and a 16% reduction for women 50 to 59, USPSTF found.

Several factors could explain the discrepancy between the findings from the Canadian trial and the USPSTF meta-analysis, Harris wrote. One is that the treatment of breast cancer has improved, and another -- at least for women 50 to 59 years -- could be attributed to clinical breast examination.

"Perhaps CBE is better than we thought, and mammography reduces breast cancer deaths when compared to no screening (or poor CBE) but not when compared to excellent CBE," he wrote.

But the bottom line is that the message of the Canadian data and the USPSTF meta-analysis is the same, according to Harris.

"What they're saying altogether is that there's probably a benefit to screening mammography, but it's really small," he told AuntMinnie.com.

When the problem of overdiagnosis is added to the mix -- roughly 22% of cases of screen-detected invasive cancer -- the fact that screening mammography is not a magic bullet becomes even clearer, Harris said.

"Screening adds to the overall breast cancer burden with false positives and overdiagnosis," he said. "So in that case, maybe we ought to stop putting all our eggs into one basket, and stop thinking of screening as the only way to address the problem of this disease."

Harris suggested that clinicians need to take a big-picture perspective, encouraging women to change their lifestyles in ways that have been associated with reduced breast cancer risk, such as maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding alcohol.

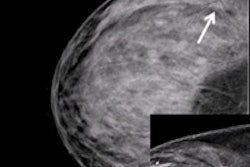

"Some researchers are framing it this way: If the current screening test doesn't work, we need to find another one -- like tomosynthesis or MRI," Harris told AuntMinnie.com. "I'm not saying these things shouldn't be investigated, but then again, if you start screening with a more sensitive test, you may reduce the number of women dying by a little bit, but you'll almost certainly increase overdiagnosis by a lot. We shouldn't pin all our hopes on screening, but rather expand our efforts to improve treatment and women's lifestyles. This back-and-forth about screening mammography just isn't getting us anywhere."

A whole new trial?

In their opinion piece, Dr. Peter Jüni and Marcel Zwahlen, PhD, take a different tack, suggesting that it's time to start another trial altogether, especially since more than 50 years have passed since the first mammography screening trial was initiated. None of the trials were conducted in the era of modern breast cancer treatment, the authors noted.

"How certain is the magnitude, or even the existence, of a benefit of screening mammography today? Does the currently assumed benefit of screening outweigh the harms of breast cancer overdiagnosis?" they asked. "Endless rehashing of data from old trials cannot provide definitive answers to these questions. The only way to know for certain is to initiate a new trial in the era of contemporary screening technologies and breast cancer therapies."

How would a new trial be structured?

"The trial would need to compare a strategy of screening every two years for five to 10 years to a strategy without systematic screening in approximately 200,000 women aged 50 to 65 years," Jüni told AuntMinnie.com via email. "Women in the control group would get the best clinical care in accordance with established guidelines, but no systematic screening. The decision to systematically invite for screening or not would be the only difference between experimental and control group, and the women would be followed for at least 15 years."

Jüni conceded that such a trial could be difficult to conduct in the U.S.

"Such a trial would be more feasible in European countries than in the U.S. because the expectations of U.S. women about the effects of screening are more unrealistic than in Europe," he said.