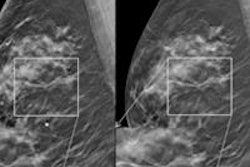

When used with digital mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) has been shown to improve the diagnostic accuracy of breast cancer screening and diagnosis. But exactly how and where is it being used in the U.S.? Researchers investigated this question and presented their findings in the June issue of the Journal of the American College of Radiology.

Dr. Lara Hardesty and colleagues from the University of Colorado at Denver conducted a survey among members of the Society of Breast Imaging to assess the use of DBT and the criteria clinicians apply to decide which patients will be offered the technology. Although breast tomosynthesis is becoming more common in clinical practice, it is still a limited resource, and a variety of factors influence how practices make use of DBT, the group found (JACR, June 2014, Vol. 11:6, pp. 594-599).

"When we sent out our surveys, the technology had been approved for about a year," she told AuntMinnie.com. "We could tell that the use of DBT was spreading, but there wasn't much information on how people were using it."

Dr. Lara Hardesty from the University of Colorado.

Dr. Lara Hardesty from the University of Colorado.Hardesty and colleagues created an online survey for physician members of SBI. The survey included questions about the availability of DBT at the participant's practice, whether DBT was used for clinical care or research, clinical decision rules guiding patient selection for DBT, costs associated with the technology, plans to obtain DBT, and breast imaging practice characteristics.

In all, 670 members responded, for a response rate of 37%. Of these, 200 (30%) reported using breast tomosynthesis, with 89% using DBT clinically. Academic practices, those with more than three breast imagers, or those with seven or more mammography units were more likely to report DBT use.

As for criteria used to select patients who would undergo DBT, 107 participants (68.2%) used exam type (screening versus diagnostic) to make the decision, 25 (15.9%) used mammographic density, and 25 (15.9%) used breast cancer risk, according to Hardesty and colleagues.

Currently, there is no CPT code for DBT, Hardesty said. Of the 177 survey respondents using DBT clinically, 47 (26.6%) charged patients an upfront fee for the service, 122 (68.9%) did not charge at all, and eight (4.5%) declined to answer. Fees for DBT ranged from $25 to $250, with the average fee being $69.

Among the survey respondents not using breast tomosynthesis in clinical practice, 62.3% planned to begin using it in the future: 12.6% planned to do so within six months, 19.5% within six to 12 months, and 29% within one to two years. About a quarter of the survey respondents did not know when they planned to obtain DBT, and 14% said they would add the technology once a valid CPT code was available.

The use of breast tomosynthesis varied geographically as well. The majority of DBT users were in the Northeast and the West (36.9% and 32.8%, respectively), with the Midwest coming in third and the South fourth (25% and 18.4%).

Although breast tomosynthesis has made the transition from a research technology to a clinical one, it's far from being the standard of care, according to the authors.

"Even among those using DBT for patient care, only 11.3% reported performing all clinical mammograms using DBT," they wrote. "Several barriers block adoption. The cost of converting all of a practice's existing mammography units to DBT units at one time is likely prohibitive and has probably slowed adoption. [And] without a CPT code, radiologists may be reluctant to adopt the new technology and pass the costs on to patients."

Clinical guidelines for breast tomosynthesis usage would help practices determine whether to adopt DBT and what patients would benefit the most from the technology, Hardesty and colleagues wrote. And a reimbursement code would help.

"Standardization of reimbursement for DBT via the adoption of a CPT code would help practitioners make adoption decisions based on science, rather than cost," the group concluded.