Stereotactic partial breast irradiation could be a nonsurgical treatment option for some early-stage hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancers, suggest findings published November 14 in JAMA Network Open.

A team led by Asal Rahimi, MD, from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas found that delaying surgery by more than nine months after irradiation led to high pathologic complete response rates combined with near-complete response rates. It also reported that treatments were tolerable up to 38 Gy.

“These findings pave the way for possible nonsurgical treatment of selected patients with early-stage HR+ breast cancer in the future,” the Rahimi team wrote.

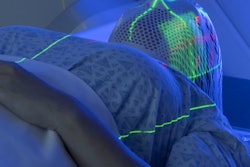

Stereotactic partial breast irradiation techniques and adaptive radiation can help with precise targeting of tumors, while delivering higher doses as the technology improves, the researchers highlighted. However, they noted that more data are needed regarding optimal dose fractionation and its association with pathologic complete response rates. This approach could help women avoid surgery.

Rahimi and colleagues investigated the maximum tolerated dose of stereotactic partial breast irradiation in a phase one nonrandomized clinical trial. They also studied clinical outcomes, including pathological complete response, time to surgery, and toxic effects associated with increases in dosage.

The study included 44 women with HR+ breast cancer. The women were treated with 30 Gy (n = 14), 34 Gy (n = 15), or 38 Gy (n = 15) using an MR-guided linear accelerator (MR-LINAC), robotic radiosurgery, or a cobalt stereotactic unit. They also received endocrine therapy and delayed surgery for 12 months. The team noted that the maximum tolerated dose was not reached in all women.

Women who underwent irradiation at 38 Gy experienced the highest pathological complete response and near-complete pathological response rates.

Treatment response rates in women undergoing stereotactic partial breast irradiation | |||

Measure | 30 Gy | 34 Gy | 38 Gy |

Complete pathological response | 35.7% | 46.7% | 66.7% |

Near complete pathological response | 64.3% | 93.3% | 93.3% |

Complete pathological response (surgery more than nine months after irradiation) | 100% | 66.7% | 64.3% |

Combined near and complete pathological response (surgery more than nine months after irradiation) | 100% | 83.3% | 92.9% |

The team also reported 100% local control, and one woman experienced surgical complications. And while the mean Ki-67 was 11.3% at diagnosis, it was 1.9% on evaluable residual disease (p < 0.001). (Ki-67 is a protein that signals cell proliferation.)

Other findings the researchers highlighted included the following:

The optimal cutoff for the time-to-surgery threshold was 277 days, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.77.

For all women who underwent surgery more than nine months after partial irradiation, the pathological complete response rate was 72%.

Longer time to surgery was tied to pathological complete response, with an odds ratio of 1.02 (p = 0.005).

Acute toxic effects included 32 grade one events, three grade two events, and one late grade three event.

Finally, the team reported a significant reduction in the tumor size on post-treatment MRI (1.3 cm vs. 0.67 cm; p < 0.001). However, it did not find any links between residual enhancement and treatment response status. The team found residual enhancement in 42.1% of women who achieved pathological complete response. This suggests challenges in predicting treatment success based on imaging, the team wrote.

The study authors highlighted that high single-fraction doses “will be useful for studies in which definitive radiation can be tested and other studies will need to test single- versus multifraction regimens on pathological complete response rates.”

Read the entire study here.