The use of thermography in place of conventional mammography for breast screening was the subject of a critical news segment on the TV show "Good Morning America" on February 13. The segment profiled two California women -- one of whom later died -- whose cancers were missed by thermography.

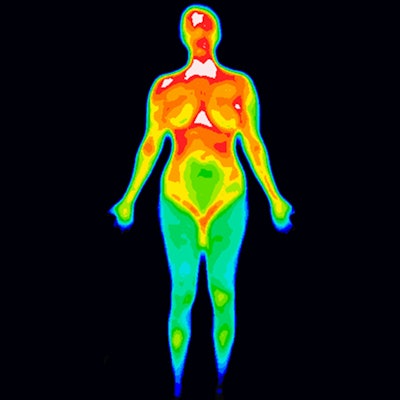

Thermography is an infrared imaging technique that shows patterns of heat and blood flow at or near the surface of the skin. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cleared some thermography devices for use as an adjunct to conventional mammography for breast imaging, but the agency has issued a number of warnings stating that thermography should not be used as a standalone breast screening modality.

That hasn't stopped a cottage industry of thermography proponents from springing up in recent years. Despite the FDA warning, many of these sites position thermography as a standalone, radiation-free alternative to mammography that can screen women for breast cancer.

Some 700 thermography sites have appeared across the U.S., according to the "Good Morning America" segment. Many of these sites are making questionable claims about thermography, such as the contention that it can detect cancer "eight to 10 years prior to mammograms," in the words of one thermography provider.

The segment profiled two women who received thermography exams. One of the women, Morganne Delain, said she visited a thermography provider in Southern California in 2012 after finding a lump in her breast. She sought out thermography because she wanted to deal with the lump "naturally," according to the show.

After Delain's thermography exam, she was told she had a "mild to moderate risk of developing aggressive tissue," and she was instructed to perform exercises and a cleanse and to return three months later for a follow-up scan. As her symptoms became worse, she decided to forgo thermography for conventional imaging; her diagnosis was stage III breast cancer.

"Good Morning America" reporter Kyra Phillips questioned the operator of the thermography clinic as to why Delain was not referred for medical treatment. His response was that a three-month follow-up thermography exam was necessary "to understand the results." Delain is now "cancer-free" after receiving conventional treatment.

The second thermography patient, Alma Arciniegas, was not so lucky. She was screened at a thermography clinic in Northern California and got the "all clear," according to her son. Six months later, she received a diagnosis of stage III breast cancer that eventually spread to her brain. She died in 2015.

Phillips also went for a thermography screening of her own, recording the exam with a hidden camera. She received a diagnosis of "mild to moderate risk of developing aggressive tissue" -- similar to Delain's. Phillips went on to have a conventional mammogram that was normal.

"People have looked at thermography as an early detection tool," said Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, interim chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, in an interview with Phillips. "The data just doesn't support it as being effective."