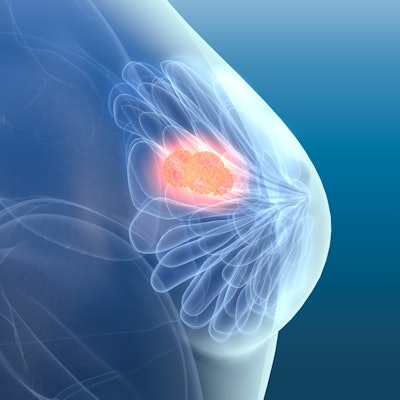

A baseline mammography exam at age 40 for average-risk women to identify breast density appears to be cost-effective, according to a study published February 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The microsimulation modeling study evaluated various scenarios for mammography screening, including baseline testing at age 40 and more intensive screening for those with breast density, which is a known risk factor for breast cancer.

For women with average risk for breast cancer, it makes clinical and economic sense to perform a baseline mammogram at age 40, followed by annual screening for those with dense breasts and biennial screening starting at age 50 for those who do not have dense breasts, reported a team led by Ya-Chen Tina Shih, PhD, chief of cancer economics and policy at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

"Compared with other screening strategies examined in our study, this strategy is associated with the greatest reduction in breast cancer mortality and is cost-effective but involves the most screening mammograms in a woman's lifetime and higher rates of false-positive results and overdiagnosis," the authors wrote.

The findings are at odds with guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which recommends screening starting at age 50 with biennial screening subsequently, and the U.K.'s National Health Service (NHS), which backs triennial screening starting at the same age. The USPSTF is currently performing a review of its guidelines.

The current study, which was funded by a grant from the U.S. National Cancer Institute, was aimed at evaluating the costs and potential harms associated with the identification of women with dense breasts at the age of 40.

Density, which is discovered through mammography, has been appreciated as a breast cancer risk factor since 1976 and in more recent years has gained attention from advocacy groups and legislators, the authors noted. Since February 2019, providers have been required by federal law in the U.S. to notify patients of breast density, but women who follow screening guidelines may not get that important information until the age of 50, the authors wrote.

Researchers used a microsimulation model informed by several data sources to assess screening strategies, subsequent diagnostics and treatments, diagnoses of breast cancer, and deaths. They modeled outcomes for a population of 500,000 women born in 1970 and with an average risk for breast cancer. Density was defined as BI-RADS categories C and D -- about 50% of women in the U.S. fit this description.

The preferred strategy turned out to be baseline screening at age 40 followed by annual screening between the ages of 40 and 75 for those with dense breasts, with biennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breasts. This was based on an analysis showing a cost-effectiveness ratio of $36,200 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) compared with a biennial strategy from age 50 to 75, whereas a threshold of $100,000 per QALY is generally considered acceptable in the U.S.

With baseline screening results available at age 40, patients and their physicians can decide on a lifetime screening strategy together, the researchers suggested.

"This baseline assessment can be expanded to collect other information, such as family history or polygenic risk scores, to further develop a risk profile that allows more targeted and personalized screening," Shih and colleagues wrote.

However, the study findings may get some pushback, based on an accompanying editorial also published February 8 in Annals. In the editorial, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) epidemiologists Dr. Karla Kerlikowske and Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, made the case for keeping the starting age of 50, with biennial screening to age 75 for women at average risk. In particular, they flagged the high cost of annual breast screening and harms of overdiagnosis.

The modeling assumed a higher benefit for mammography screening than has been reported in other studies and magnified the number of deaths averted, they suggested in the editorial. Furthermore, only 24% of women with dense breasts are at high risk for a missed invasive cancer within one year of a negative mammogram and they can be identified without the need for more frequent mammography screening, the authors wrote.

Kerlikowske and Bibbins-Domingo instead favored a focus on overall risk for screening, including breast density, in order to maximize benefits while minimizing harms. Aside from density, risk factors include age, a family history of breast cancer, and a history of breast biopsy.