New eyewitness accounts further make the case that two Canadian randomized trials conducted in the 1980s should not be used in breast screening meta-analyses or to inform policy, according to commentary published in the Journal of Medical Screening.

A team led by Dr. Martin Yaffe from the University of Toronto shared new eyewitness accounts that reported randomization flaws in the Canadian National Breast Screening Studies (CNBSS), both of which found no benefits from routine mammography. These eyewitnesses revealed cases in which symptomatic women were shifted from the control group to the mammography group, according to the researchers.

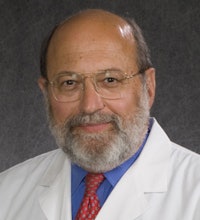

Dr. Daniel Kopans.

Dr. Daniel Kopans."The studies violated the most fundamental rules for randomized, controlled trials and should not be used to determine screening guidelines," commentary co-author Dr. Daniel Kopans from Harvard University told AuntMinnie.com.

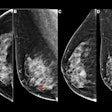

The two breast screening trials began in Canada in 1980 in an effort to find out if routine screening of women ages 40 to 49 with screen-film mammography and clinical breast examination lower breast cancer mortality compared with usual care, as well as if such screening and examination in women aged 50 to 59 reduce mortality beyond that obtained with examination alone.

Neither study found benefits, and breast screening experts over the years have raised concerns about these trials, including the randomization process, poor image quality, and flaws in recruitment methods, among other factors. Now, new eyewitness accounts have emerged that detail what researchers are calling "serious protocol violations" that subverted randomization and make the trial results unreliable.

"In order for the results of randomized control trials to be valid, blinded allocation is essential" Kopans wrote in a separate overview. "Unfortunately, this fundamental rule was ignored by the studies."

The researchers said that women presenting with breast cancer symptoms were recruited into the trial. However, these trials were intended to focus on screening, which would benefit women who were asymptomatic. The team wrote that women who have symptoms are unlikely to benefit from screening and require diagnostic workup, including imaging.

They also noted that some screening centers that worked with the trials saw lower recruitment numbers, leading to women being recruited from breast surgeon practices.

"The likelihood of these women being asymptomatic would have been very low," they said.

Furthermore, the researchers said they talked with medical professionals at these sites, and that 17 of these personnel stated they were aware of symptomatic women being recruited. With some of these women "undoubtedly" having breast cancer, the team wrote that these numbers would have contributed to deaths in the studies, as well as added a systematic bias.

Yaffe et al also said that medical personnel described women being shifted from the control group into the mammography group, and that misrandomization of even a few women with advanced breast cancer could affect measured screening efficacy.

The team also pointed out that except for one of the 15 study sites, all women received a clinical breast examination by a trained nurse examiner being registered in the studies. Citing previous investigations, the group said this may have caused women to be reallocated into part of the study that measured both mammography and clinical breast examination.

One person researchers said they spoke to in March after a lecture addressing randomization confirmed compromised randomization of the trials. The person, a mammography technologist, worked at the St Michael's Hospital site of the studies. Her name was left out of the commentary.

"She reported that some women with breast lumps were deliberately assigned to the mammogram arm of the study, rather than blindly randomized," the commentary authors wrote.

They also wrote that the technologist's testimony was supported by "very high" screen-one cancer detection rate in the hospital's mammography arm, reportedly higher than at other sites and 12 times higher than the clinical breast examination arm. The benign-to-malignant ratio at biopsy at this site was also low compared with other sites, which researchers said suggest the prevalence of larger, easily detected cancers.

"Subsequently, another eyewitness, a radiologist at a separate screening site in a different city, came forward with information about serious protocol violations at that site," they added.

Although the researchers said they believe that coordinators and nurses with no prior experience in randomized control trials had good intentions, study design protocols allowed for nonrandomization.

"The data have always suggested that this happened; and now we have firsthand testimony that this took place," Kopans said. "These violations have hopelessly corrupted the results. It is now clear that the CNBSS trials were fundamentally compromised, and the trials' results are unreliable."