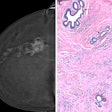

Location, location, location. It's true in real estate, and it may be true in healthcare as well, at least according to the authors of a study published January 27 in JAMA Oncology, who found that where patients live is perhaps the biggest determinant of the quality of breast cancer treatment they receive.

The researchers found that there were major variations in the quality of breast cancer care patients received based on the region they lived in -- much more so than demographic factors such as race and ethnicity. Efforts to improve healthcare quality should focus on these regional variations, they advised. Even so, the researchers found that the biggest variations in breast care were unexplained.

A team led by Dr. Michael Hassett from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston found that reducing unwarranted random variation across the country rather than focusing on specific at-risk patient subgroups or poor-performing regions could help. The exception to this is that improvement efforts targeting a few low-performing regions could help reduce variation in endocrine therapy and radiation therapy, the group found.

"Regional approaches targeting endocrine therapy may do more to improve outcomes compared with interventions targeting other treatments or specific patient subgroups," Hassett and colleagues wrote.

Research has shown disparities in breast cancer mortality among vulnerable populations, such as Black individuals, people living with low income, older adults, and people living in rural areas. Differences in cancer biology, stage at diagnosis, and initial cancer treatment contribute to the higher rates of death seen in these groups.

County-level data shows that breast cancer mortality varies from 11.2 to 51.6 deaths per 100,000 women. The researchers said this four-fold difference argues "strongly" in favor of an intervention targeting healthcare delivery system factors.

While screening mammography and breast cancer treatments are significantly associated with patient demographic factors, geographic factors as determinants of treatment have been less studied.

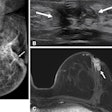

Hassett et al wanted to find out the extent to which geospatial variation in initial breast cancer care can be attributed to region versus patient factors, with the aim of guiding quality improvement efforts. This included describing regional variation with five metrics, including the following:

- Stage of cancer diagnosis

- The use of recommended chemotherapy

- The use of radiation therapy

- Starting endocrine therapy

- Continuing endocrine therapy between years three and five

"We know that breast cancer treatments and outcomes vary by region and patient factors, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and age, but don't have a good sense of which is more important," Hassett told AuntMinnie.com.

The team looked at data from 31,571 patients with newly diagnosed, nonmetastatic breast cancer who were observed for at least three years. The median age of the patients was 71. Out of the total, 19,391 (61.4%) had stage I disease at diagnosis.

Among eligible patients, 17,297 of 21,190 (81.6%) received radiation therapy, 7,204 of 9,903 (72.8%) received chemotherapy, 13,115 of 26,855 (48.8%) began endocrine therapy, and 13,944 of 26,855 (52.1%) continued endocrine therapy.

The researchers found that geospatial density "heat" maps showed that region and hospital service area (HSA) explained more variation in the types of breast cancer treatments patients received (24%-48%) than patient factors (1%-4%). The largest share of variation, from 35% to 54%, was unexplained, the study authors wrote.

They also found that the types of breast cancer treatments with the largest proportion of total variance attributed to region and hospital service area were endocrine therapy initiation (28%) and endocrine therapy continuation (39%).

Hassett said "very little" of the observed regional variation can be attributed to patient factors and that most of the observed geospatial variation "is random and cannot be explained."

The authors wrote that it will be critical to best use limited resources to improve outcomes and reduce disparities, considering that quality improvement "is costly and time-consuming." They also called for future efforts to identify other variables to understand unexplained variation and develop strategies that work across health care delivery systems.

Hassett told AuntMinnie.com that the team is looking at how to identify low-performing regions and whether breast cancer outcomes also vary by region.