About one-fourth of physicians do not consider life expectancy a good enough reason to stop cancer screening in older adults, a study published October 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine found.

Researchers led by Dr. Nancy Schoenborn from Johns Hopkins University highlighted that their findings question whether physicians and patients would accept reframed guidelines that shy away from using life expectancy as the standard for ending cancer screening.

"Even among those who supported using life expectancy, almost half had concerns it may introduce bias and over one-third thought the current tools we have for predicting life expectancy are not accurate enough," Schoenborn et al wrote.

Previous research suggests that cancer screening's value declines as people become older. Current guidelines recommend against routine cancer screening when life expectancy is less than 10 years.

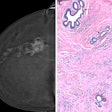

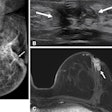

However, many older adults still undergo such screenings. For example, a 2022 study found that about 76% of breast cancer survivors aged 80 and older still have annual mammograms.

Physicians have debated over the years whether using life expectancy as a benchmark for determining when cancer screening should stop is suitable. Schoenborn and colleagues wanted to assess attitudes physicians have about using this measure as a standard for cancer screening cessation. Specifically, they wanted to find out whether a less than 10-year estimated life expectancy was a suitable range.

The team looked at survey data from a total of 791 physicians. Of these, 600 were primary care physicians who specialized in internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, and geriatric medicine. They were surveyed about breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screenings for people aged 65 years and older. The other 191 included in the study were gynecologists who were surveyed solely about breast cancer screening in women in the same age range.

The researchers found that 75.3% (n = 596) of the total study population agreed that life expectancy of less than 10 years was a reasonable standard for stopping cancer screening. This includes 81.3% (n = 488) of primary care physicians and 56.5% (n = 108) of gynecologists (p < .001).

The team also found that while 64.4% physicians agreed that reducing overscreening is part of good patient care, only 38.8% perceived overscreening as a substantial problem in older adults.

The physicians seemed split on the issue of the life expectancy standard potentially introducing racial and socioeconomic bias. The study authors noted that 45.4% of physicians believed using this standard may introduce bias against racial and ethnic minority individuals, while 48.4% believed it may introduce bias against people with low socioeconomic status.

The team called for guidelines to better evaluate and raise awareness of ways that prediction algorithms may entrench existing biases.

Schoenborn told AuntMinnie.com that the team is analyzing some related results in which they asked about various criteria for stopping cancer screening. The researchers want to see which alternatives to 10-year-life expectancy are acceptable from the physicians' perspective.

"I think one next step would be to understand the perspectives of radiologists regarding what would be reasonable criteria for stopping screening," Schoenberg said.