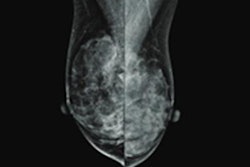

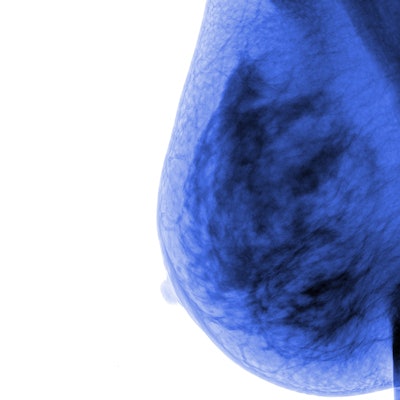

Mammographic breast density may decrease with age, but the process is slower in women who develop breast cancer, according to research published April 27 in JAMA Oncology.

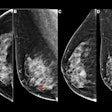

A team led by Shu Jiang, PhD, from Washington University in St. Louis, MO, found significantly slower declines in breast density for these women than in women who don't develop breast cancer by using longitudinal digital mammograms of each breast during up to 10 years.

"For the past couple of decades, we've known that women with more dense breasts are at higher risk of breast cancer, and that's all that we've done in assessing risk and predicting future risk," co-author Dr. Graham Coldtiz told AuntMinnie.com. "This [study] really adds another dimension to understanding risk for breast cancer."

Breast density is a known risk factor of developing breast cancer, but density seems to naturally decrease over time in women, linked to decreasing hormone levels. However, the researchers noted that there is limited data tying density change over time and risk of subsequent breast cancer diagnosis in women. They wrote that there may be a difference in rate of density change between women who develop second cancers and those who don't.

Jiang and colleagues conducted a study that used information from digital mammograms for a 10-year time period to evaluate the association between the rate of mammographic density change and risk of developing breast cancer.

The research included data from 947 women. Of these, 763 (80.6%) were white, 141 (14.9%) were Black, 20 (2.1%) were of other race or ethnicity, and 23 (2.4%) did not report their race or ethnicity. Average interval from the last mammogram to the date of subsequent breast cancer diagnosis was two years.

The team found that breast density decreased over time in both case and control groups. However, they also found that mammograms for breasts that subsequently developed cancer showed a significantly slower rate of decrease in density than mammograms from women who did not later develop cancer.

The study results could improve how breast cancer risk is classified, the team noted.

"These repeated measures can be further refined for routine practice and incorporated into a dynamic risk classification and hence guide personalized prevention services according to the woman's level of risk," they wrote.

Colditz said the additional refinement of understanding the trajectory of change in density as seen in this study will add to prediction models and at some point. This includes better refining which women with dense breasts are more at risk than others and strategizing for risk reduction.

"I expect that it [model] will be an automated component for reviewing mammograms to see the difference in the rate of breast density decline over time," he said.

He added that the team's next step is to explore more factors besides breast density, and to focus on incorporating entire mammography images into a prediction model rather than a summary of individual features.

"There are millions of pixels in a mammogram image, and historically we've summarized this into a four-point scale which seems pretty crude now," he said. "There are lots of other features that can contribute to refining the level of risk for a particular breast."