Using structured rather than narrative reporting for CT made patient management much clearer for pancreatic cancer surgeons, as it is less likely to leave out important information needed to determine whether tumors can be surgically removed, according to a study in Radiology.

Radiologists using a narrative reporting style frequently left out key descriptors from their report, resulting in pancreatic surgeons not knowing if the tumor was resectable, reported researchers from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and other institutions (Radiology, October 3, 2014).

Dr. Olga Brook from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Dr. Olga Brook from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center."Our study of pancreatic surgeons ... showed that they also like structured reporting -- they are looking for very specific things that are missing from our reports if we don't use structured reporting," lead author Dr. Olga Brook told AuntMinnie.com. "They also get more relevant information regarding pancreatic cancer."

Radiologists are well aware of what pancreatic surgeons need, she said, but everyone forgets things, and without structure even the best of them forget to put things in.

"That's why a checklist is so important ... and that's what this is," said Brook, who is an assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and a radiologist in abdominal imaging and interventional radiology at Beth Israel.

Structure is good, probably

Medical literature on the utility of structured reports is incomplete. Studies have shown that referring clinicians prefer structured radiology reports because they are clearer to interpret, but that perceived clarity has not been shown to improve results objectively.

On the other hand, there is evidence that the rigidity of structured reporting templates can actually reduce accuracy, and radiologists complain that they are time-consuming, a factor that may explain the lack of widespread adoption of structured reporting, the authors wrote.

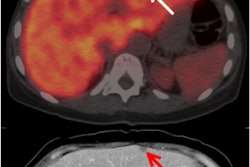

CT is considered the workhorse modality in pancreatic cancer imaging because it can clearly delineate the relationship between tumors and vascular structures to assess invasion and inform the decision about whether surgical intervention is possible.

Multiphasic CT can also assess congenital anatomic variants of the arteries and biliary system, allowing clinicians to minimize the potential morbidity associated with surgical intervention.

"Thus, detailed description of vascular anatomy, local tumor invasion, and presence of distant metastases are of utmost importance," Brook and colleagues wrote.

Differences in usefulness?

In 2008, Beth Israel became an early adopter of templates for multiphasic CT of cancer; pancreatic surgeons said they improved the delivery of information to help surgeons make crucial patient management decisions.

The tumor template contained detailed information for surgical and oncologic decisions about the organ, including tumor size, location, enhancement, node status, and vascular involvement. RSNA adopted a similar reporting initiative in 2011, the authors noted.

The study examined all patients referred for multiphasic CT of the pancreas between 2006 and 2011 before and after implementation of the structured reporting template, which went into effect gradually.

In all, 48 (40%) structured and 72 (60%) nonstructured reports were reviewed, Brook and colleagues reported.

The research team performed multiphasic CT on a 64-detector-row CT scanner (VCT, GE Healthcare). The protocol included a low-dose unenhanced scan at 120 kVp, maximum 200 mAs, and 64 x 0.625-mm collimation, reconstructed at 5 mm. Unenhanced, portal venous, and late arterial phase acquisitions were obtained.

Coronal and sagittal reconstructions (5-mm thick slices) of arterial and portal venous phase acquisitions, maximum intensity projections for evaluating arterial and venous structures, and volume-rendered images in most cases were sent to PACS for radiologist review.

Radiologists evaluated the images for 12 key features necessary for planning pancreatic tumor resection. Questions assessed tumor location, probable diagnosis, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, and superior mesenteric artery and vein involvement. They also asked about the presence of thrombosis, the presence of atherosclerotic plaque, and the distance from tumor to the superior mesenteric vein.

A fellowship-trained radiologist reviewed all structured and nonstructured reports. Three pancreatic surgeons reviewed the reports independently. They were asked if the tumor was resectable (yes/no/unsure), whether there was sufficient information for surgical planning in the report (yes/no), and whether it was easy to extract surgical planning information from the report (easy/needs some effort/difficult).

Two weeks later, surgeons reviewed the images without the report and again answered the question about resectability. Finally, they reviewed the images with the reports and were asked to render final decisions about tumor resectability.

Key information in structured reports

Structured reports contained significantly more key features than nonstructured reports, the group found. Of the 12 key features in the reports, nonstructured reports contained a mean 7.3 features ± 2.1 (range, 1-11), while structured reports contained a mean 10.6 features ± 0.9 (range, 9-12; p < 0.001).

As for surgical planning information, the three surgeons rated it easily accessible at rates of 94%, 60%, and 98% in structured reports, versus 47%, 54%, and 32% in nonstructured reports (p < 0.001, p = 0.79, and p < 0.001, respectively).

Similarly, the three surgeons said they had sufficient information for surgical planning in 96%, 69%, and 98% of structured reports, compared with 31%, 43%, and 25% of nonstructured reports (p < 0.001, p = 0.009, and p < 0.001).

Finally, when the surgeons reviewed reports in combination with the CT images, they were more likely to convert an answer of "unsure" regarding resectability to a definitive answer of resectable or unresectable when reading structured versus nonstructured reports.

Key features more frequently left out of nonstructured reports included probable diagnosis, tumor staging, superior mesenteric artery and vein involvement, presence of vessels showing thrombosis, presence of a replaced right hepatic artery, and other aberrant anatomy, the study team wrote.

"Our results confirmed that radiologists who used narrative reporting of multiphasic CT frequently omitted multiple key descriptors that surgeons desired for surgical planning for patients with pancreatic cancer, and there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of key descriptors omitted with the implementation of structured reporting," Brook and colleagues wrote.

Structured reports were more likely to have enough essential information for surgical planning, and it was easier to extract the necessary information to decide patient management from a structured than a nonstructured report.

In Brook's view, simply reconstructing more thin-section images wouldn't have helped as much as tailoring the report did.

"When we do coronal and sagittal reconstructions, we are using thin sections to make those reconstructions very clear to the eye," she said. "But the 5-mm thick images are much better to see."

1 of 2 pancreatic cancer templates

Beth Israel's template isn't the only game in town. Since the institution developed its structured reporting template for pancreatic cancer in 2007, RSNA -- in a project funded by the U.S. National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering -- began creating a library of "clear and consistent" report templates, according to the authors.

The pancreatic cancer template, developed in cooperation with Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Pancreatic Association, was released in 2011. According to Brook, it is more complex than what was used in the study.

"It has many more ... descriptors," she said. "Our system is shorter, but we think it has all the important information that is needed."

Perhaps more important for radiologists who must answer all of its questions, the shorter template strikes a good balance between brevity and quality, Brook added.

Extra questions in the newer pancreatic cancer template may be important for research and other implementations, "but they're not as strictly important for surgical planning," she said. "If surgeons need more information, it's always available."

Raptopoulos et al also created a good system that correlates findings to increasing probability of unresectability and positive surgical margins after resection, the authors noted.

Beyond the pancreas

Expanding the structured reporting model to other indications -- especially several other exams that approach the complexity of CT for pancreatic cancer resection -- is a good idea, Brook said.

"I believe that structured reporting should be tailored to specific entities," she said. "We are also developing very specific Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma," she said. "They have very specific criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma -- when it's resectable, when it's not resectable, when [the liver] is transplantable, etc. If it's hepatocellular carcinoma it has a certain size, certain enhancement, certain washout, and other criteria, and if it doesn't meet the criteria, the patient will not get a transplant. So there are other areas where structured reporting can be utilized."

The hepatocellular carcinoma template and another being developed for pancreatitis won't be in the form of a full structured report; rather, they will be supplements to the full report.

Beth Israel's methods were developed in 2007 -- years before the rollout of a proposed national structured reporting model that became far more comprehensive and detailed. But her center's methods are both concise and complete, getting to the heart of what surgeons need, she said.

"We really wanted to have the items that are important for surgical staging; for the rest, we can always provide more details," Brook said.