Sharing patient data on Facebook and WhatsApp involves a breach of European data protection regulations and can have serious consequences, according to Dr. Erik Ranschaert, PhD, president of the European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics (EuSoMII). At today's Special Focus session, his goal was to raise awareness of secure alternatives.

He recalled a story from 2013, when an assistant surgeon from the Sacred Heart Hospital in Lier, Belgium, hit the news headlines for all the wrong reasons. The surgeon posed with large metal cutting pliers above a patient's leg, explaining this was just a normal day in the orthopedic operating room and posted the photos on Facebook.

Dr. Erik Ranschaert, PhD.

Dr. Erik Ranschaert, PhD."It was intended to be a joke, but the Belgian board of physicians asked for an official investigation because he -- and the hospital -- were identified," said Ranschaert, adding that it would also have been relatively easy to identify the patient. "And this makes it quite dangerous: Data are vulnerable, and its exposure can have serious consequences."

His talk today focused on the risks of radiologists using social media and messaging services. No less than 40% of medical specialists at a Dutch hospital have sent patient names and pictures via WhatsApp, while a study by Google DeepMind found that doctors use Snapchat to send scans to each other.

"One of the main reasons is there is a need for fast communication. It is an easy way to efficiently share medical data," noted Ranschaert, adding that a resident might want to get a second opinion on a scan from an interventional radiologist, and if the patient is in a life-threatening situation, every second counts.

However, it is now important to consider the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). When radiologists share images, they must secure the explicit consent of the patient. Moreover, Snapchat or WhatsApp don't allow audit or access control to images, and there is no guarantee the data can be permanently deleted, he explained.

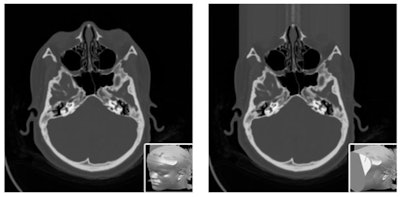

A screenshot of a brain CT with hemorrhage, using the Siilo app. It is possible to add arrows and manually erase some information (blurring on the bottom). Image courtesy of Dr. Erik Ranschaert, PhD.

A screenshot of a brain CT with hemorrhage, using the Siilo app. It is possible to add arrows and manually erase some information (blurring on the bottom). Image courtesy of Dr. Erik Ranschaert, PhD.Ensuring patient consent was also the topic of a talk by Dr. Osman Ratib, PhD, a professor of Medical Imaging at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He noted that GDPR permits general consent, whereby patients agree their data can be used for research, without specific information about the research studies that will use the data. The insurance is that a specific study must be approved by an ethics committee.

Under general consent, images and related data are anonymized, but the patient still has rights and can withdraw from future projects, Ratib added. To eliminate the anonymous data, there must be a secure code linking the data to the patient's identity.

"It is complex to implement and has a cost, and as we move toward open data and imaging biobanks, we need to discuss who will carry the cost of data tracking and data management to ensure proper security and compliance with data protection regulations," he said.

There is also the question as to whether patients can give up their rights and "donate" their own data, which is legal in the U.S., where patients can sell their data, but may be illegal under GDPR. These problems must be overcome before radiologists can benefit from big banks of images for research, he noted.

Ratib's talk will largely focus on data security as radiologists establish large imaging biobanks needed to train machine-learning tools. "It is necessary to ensure they are properly developed and hosted, and they reliably avoid the misuse of data -- we should concentrate the debate on that," he said. Part of that debate is how to build patient confidence in an age of widespread distrust of companies like Google and Facebook. Patients need to believe that radiological images given to researchers will be put to ethical use. He suggested that future image banks might be regulated by the ESR, RSNA, or other reputable bodies.

Patients also need to know their images are properly anonymized, he continued. "We know that with today's facial recognition, it is easy for a computer to match a reconstructed image from a CT or MR image of your head to a picture that you published on WhatsApp or the internet."

To avoid such risks, facial data from medical images can be blurred out, but this prevents studies on the nose, eyes, or sinuses to be performed on such altered data. Some data security experts recommend removing all identifying features, including blurring out tattoos on CT scans of the skin, for example. Ratib wonders how much each patient should be informed about what measures are being taken to protect the confidentiality of data.

Sensitive features can be automatically detected and hidden by covering the face with a shapeless mask of pseudorandom noise. Image courtesy of N. Roduit, University Hospital of Geneva.

Sensitive features can be automatically detected and hidden by covering the face with a shapeless mask of pseudorandom noise. Image courtesy of N. Roduit, University Hospital of Geneva."We have to tell them, 'We will do everything we can to keep your data anonymized, but there is always a risk.' If someone wants to expend enough time and effort to find you, they will, but our responsibility is to minimize that risk as much as possible," he said.

As for sharing those images, Ranschaert wants to educate radiologists and researchers about secure alternatives to public social media software, such as WhatsApp. More secure apps include TigerConnect, Forward Health, Siilo, and Medic Bleep. These are GDPR-compliant, allowing encryption, data transparency, access control, audit control, and anonymity, with formal arrangements for processing and storage, he said. Images taken with a dedicated messaging app, such as Siilo, can be securely stored on remote data servers with strict controlled access to authorized users. Even if the smartphone is stolen, the data can remain safe.

Originally published in ECR Today on 1 March 2019.

Copyright © 2019 European Society of Radiology