WASHINGTON, DC - Medical-grade displays for PACS workstations may be more cost-effective than high-quality consumer-grade LCD displays, according to a session on Friday at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) annual meeting.

What would cause Dr. David Hirschorn, director of radiology informatics at Staten Island University Hospital and an early advocate of consumer-grade monitors for medical applications, to make such a statement? It's not the quality of the display or the resolution. It's calibration, or a lack thereof.

All LCD displays need to be calibrated. A medical-grade display incorporates self-monitoring and self-calibration, or it can be remotely monitored and adjusted automatically on a 24/7 basis by an Internet-connected vendor service. Consumer-grade monitors do not have this capability, nor do they have internal alerts for when displays begin to deviate.

Calibration needs to be proactively scheduled, and someone needs to perform the calibration. Often that someone doesn't exist, is overworked and unavailable, or doesn't really know what he or she is doing. Even if a qualified individual is available to calibrate displays according to a thought-out quality assurance program, what is the cost of the person's time to calibrate what may be dozens of diagnostic workstation and technologist monitors?

Attendees at the SIIM session who listened carefully got the message that the total cost of ownership to keep consumer-grade displays on track for diagnostic use, combined with a useful lifetime that is 33% to 50% less than that of a medical-grade display, may significantly undermine a purchase price that can be 10 times less.

Hirschorn was among the first radiologists to research whether consumer flat-panel displays had resolution and brightness levels comparable to 3-megapixal grayscale medical displays and, thus, could be used with PACS diagnostic workstations. He has published a steady stream of study results since 2006, and he still believes that consumer-grade monitors are good substitutes for displaying most types of diagnostic images, with the exception of mammography exams.

However, because the brightness of consumer LCD displays begins to drop shortly after use, keeping them calibrated is imperative to maintaining diagnostic display quality.

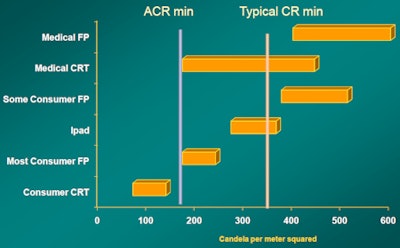

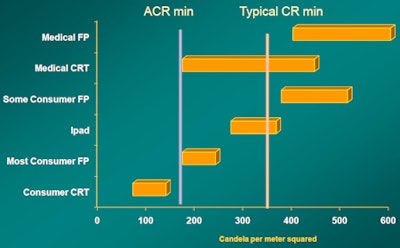

"High-quality consumer-grade LCD displays are made with a 400 to 500 candela per meter squared [cd/m2] [brightness]. This breakthrough occurred when designers found a way to make colder light bulbs, allowing backlights to be brighter without causing melting of the display," Hirschorn explained. "A brightness level of 400 to 500 cd/m2 is needed to read computed or digital radiographs; a brightness of 170 cd/m2 is fine to read other types of images, such as CT. You do not need to see subtle contrast when interpreting CT images."

However, he warned, what is advertised about a display model is one thing; the display you purchase may be another. And even if it's identical, the brightness level will soon start to change. Manufacturers of consumer LCD displays are addressing a market of buyers who may never perform a calibration during the life of the product. The brightness levels of these products drop very quickly. Consumers typically do not notice this or complain.

|

| Luminance level. Image courtesy of Dr. David Hirschorn. |

Different mindset

Manufacturers of medical-grade displays have an entirely different mindset. They want to guarantee that a diagnostic image of consistent quality that meets DICOM standards is always displayed.

For this reason, almost all medical-grade displays sold today have continuous centralized monitoring.

"The advantage of screens that can see themselves is that they know how much light is being put out, and compensate for it," Hirschorn said. "Medical displays are manufactured with extra brightness capacity that compensates over time for degradation."

A medical display may be designed with a 2,000 cd/m2 brightness that gradually deteriorates over time. But internal feedback mechanisms allow it to maintain a brightness level of 400 to 500 cd/m2 over the typical five- to seven-year life of the display.

To guarantee the visual consistency of multiple monitors that may be used in a radiology department or imaging center, remote monitoring services began to be offered by vendors. This service doesn't exist for consumer-grade displays.

Remote monitoring is mainstream. "You do it for CT scanners, you do it for PACS -- you should do it for quality assurance and PACS diagnostic workstation monitors," Hirschorn said. "For secondary review, any display is OK. But the average Joe doesn't know a thing about when a display needs calibration. Don't risk them getting out of whack."

Mobile devices

Mobile devices also have calibration issues. Shortly after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first diagnostic application for use with iPhones and iPads, Apple came out with an application that puts 10 test targets on the screen. When a person sees the target, they touch it, verifying that they can see the contrast.

This application is better than a photometer because it tests the LCD display, the ambient conditions of the viewing moment, and human perception of the image, Hirschorn said. However, once ambient conditions change -- namely, as soon as the device moves -- the application needs to be repeated.

He doesn't expect these mobile devices to become displays for primary interpretation, except on a need-for-consultation basis.

"It's easier to get a pediatric neuroradiologist to carry a mobile device around rather than a laptop, and an interpretation from that type of subspecialist may be better than anything a general radiologist can make viewing the image on a stationary diagnostic workstation," he said. "But I can't read off a postage stamp."

Hirschorn predicts that referring physicians will embrace mobile display devices to have immediate convenient access to their patients' images. He advocates this because a radiology report accompanied by select images can be more beneficial than a written report by itself. But he's concerned that mobile devices may be inappropriately used to make clinical management decisions. Looking at images in the intensive care unit to verify line placement could be a "slippery slope" with potential legal implications if a wrong decision is made.

The display of a mobile device is better than the first generation of grayscale CRT displays, but you can't ignore the fact that images are displayed with pixels that may be too small to show details needed for an accurate diagnosis, Hirschorn concluded.