Photos of patients taken at the same time they receive a portable radiography exam can yield a variety of clinical benefits for radiologists, such as reduced errors in diagnosis and treatment, according to research published online October 8 in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

"Such photographs can be useful in the detection of wrong-patient errors and provision of image-related clinical context, which can improve radiograph interpretation," wrote a team of researchers led by Dr. Srini Tridandapani, PhD, from Emory University in Atlanta.

Prior research from Emory had shown that portable chest radiography was the modality with the largest number of close calls -- by far -- related to wrong-patient or wrong-dictation results. In 2013, Tridandapani and colleagues also reported that incorporating digital photos of patients' faces into their x-ray images could decrease patient identification errors by fivefold.

In this study, the researchers shared their initial clinical experience after retrofitting smart cameras to five portable radiography systems. Wide-angle patient photos are automatically captured when the radiograph is acquired; they are then converted to DICOM and sent to the PACS as a separate series in the matching radiology study.

After the camera system was placed into clinical use, a wrong-patient error was found within the first 300 cases, and two total errors were detected in the first 8,000 cases. That rate was higher than expected; the researchers had projected a one-in-10,000 rate based on their previous retrospective research. Although longer-term studies with a larger number of examinations are ongoing to obtain statistically meaningful results, Tridandapani and colleagues were encouraged by the early detection of the wrong-patient errors.

Faster reads

In addition, users have reported benefits in chest and abdominal portable radiography, according to the researchers. Radiologists can read these cases faster "because the photographs show the external portions of lines and tubes, which can eliminate potential confusion in separating internal from external portions if radiographs alone are considered," they wrote.

For abdominal radiographs obtained to evaluate the placement of feeding tubes, if a tube were not visible on the radiograph, it would normally warrant a telephone call to the patient's nurse to confirm the tube's absence.

"For such cases, our radiologists found that they could save time by avoiding the telephone call if no tube was seen entering the nose or mouth on the photographs," they wrote. "In such instances, the radiologist could confidently assume that there was no tube present. If, however, a tube was seen in the nose or mouth, then the radiologist could make a confident call asking for repositioning or removal of the tube."

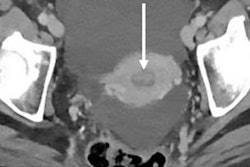

In addition, the ability to see patient monitors on the wide-angle photographs can give radiologists a quick bird's-eye view of patient vital signs, avoiding the need to gather that data from the electronic medical record. The wide-angle photographs can also add confidence for radiologists by showing that patients receiving abdominal radiographs to rule out pneumoperitoneum are in the upright or supine position.

Helpful information

The researchers noted that Emory's musculoskeletal radiologists have been particularly pleased with the laterality information provided by the patient photographs.

"Often, radiologists are unsure whether the right or left extremity was imaged, and a photograph showing patient orientation with the radiographic plate behind the limb being radiographed confirms the side being imaged," they wrote. "In fact, in a preliminary retrospective evaluation of 350 extremity radiographs, the accompanying photographs enabled identification of two wrong-side errors that had been missed in the initial evaluation without the photographs."

What's more, extremity radiographs for trauma or the evaluation of osteomyelitis in patients with diabetic foot ulcers can be interpreted faster with the photographs, which help focus the radiologist's attention on the portion of bone on the radiograph underlying the visible soft-tissue injury or ulcer, according to the researchers.

They also highlighted the intangible benefit of personalization that point-of-care photographs can bring to radiologists -- along with, potentially, more empathy for patients.

"The potential impact of this empathy on interpreting physician job satisfaction and, in turn, their interpretation performance is worthy of future evaluation," the authors wrote. "Although our prior work in a laboratory setting showed that the potential distraction effects of photographs on radiograph interpretation were limited, this needs to be studied in the clinical setting to determine whether it would inadvertently increase interpretation time."