Radiologist Dr. Douglas P. Beall spent two weeks in February at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer (HAS) in Deschapelles, Haiti, as part of a non-profit program to help hospitals develop better radiology procedures. This is the story of his visit.

A world apart

Flying into the Caribbean nation that occupies the western third of the island of Hispaniola, the terrain looks brown and arid even from 10,000 feet. Haiti, its landscape deforested and deeply eroded, looks markedly different from its eastern neighbor, the Dominican Republic.

Despite recent improvements in the nation’s economy, Haiti remains the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere. Although this Caribbean country is geographically proximal to the U.S. (a two-hour flight from Miami), the Republic of Haiti is worlds apart in terms of economic development, infrastructure, and delivery of healthcare.

The flight from Miami to Port au Prince seems similar to a short hop within the U.S., but here my arrival is heralded by unique scenery, including clear green water and mountainous terrain. And while the airport doesn't meet U.S. Federal Aviation Administration standards for security, crime is reportedly rare, and passengers appear comfortable as the customs process moves along swiftly.

Just outside a fence surrounding the rear exit to the airport, the area teems with people volunteering to carry the bags of arriving passengers. I see a welcome face -- the individual holding the sign for Hôpital (Hospital) Albert Schweitzer (HAS) -- and after the bags are loaded our two-hour trip to Deschapelles and HAS begins.

The ride to HAS is an experience in and of itself. The crowded and narrow streets of Port Au Prince have no visible stoplights. Traffic is bumper-to-bumper and moves very slowly. Drivers maneuver as best they can to navigate around obstacles in the street: mostly people, stalled cars, and livestock.

The streets are densely crowded with people and lined with kiosks selling a wide variety of goods, including food, clothing, automobile parts, furniture, and many other items. The road to Deschapelles is mostly asphalt, except for some unpaved sections that are rocky and rough enough to induce motion sickness.

The ride takes between two and three hours, depending on the time of day; waves of pedestrian traffic along the highway provide interesting sights and occasional obstacles. Our route, Highway 100, courses along the southeast coast of Haiti, offering pleasant waterfront scenery most of the way.

The accommodations are spacious villas originally built by the United Fruit Company. Luxurious by local standards, each has electricity and running water, and can accommodate up to eight people. The living quarters are immediately adjacent to the hospital, arranged in a circle with a functional swimming pool in the center. Most of the hospital staff and visiting personnel are located there, and the circular arrangement is ideal for the various social functions and for introducing newcomers to the local hospital community.

The hospital

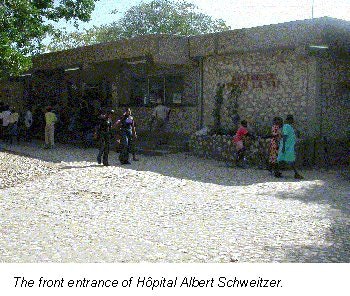

Hôpital Albert Schweitzer is a private institution located in the Artibonite Valley in the remote village of Deschapelles, 90 miles north of Port au Prince. It was founded in 1954 by Dr. William Larimer (Larry) Mellon of the Pittsburgh-based Mellon banking and oil family. Mellon had his original inspiration for the hospital in 1948, after reading a Life magazine article describing Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s hospital in Gabon, Africa. At that time Mellon and his wife Gwen were operating a cattle ranch in Arizona, and they were impressed by Dr. Schweitzer’s commitment to serving those in need.

Mellon soon contacted Dr. Schweitzer, and with Schweitzer’s encouragement decided to enroll in medical school at age 37. After graduating from medical school, Larry Mellon used $2 million from his inheritance to construct a 116-bed facility that would serve a 610-square-mile area, and dramatically increase life expectancy. Within 20 years of its opening, it would be known as the best hospital in Haiti.

The radiology department

Hôpital Albert Schweitzer's radiology department consists of two radiographic rooms, small waiting and film-viewing areas, and a darkroom where films are hand-dipped and placed in a ventilated box for drying. There is a separate ultrasound room adjacent to the outpatient clinics. Approximately 2-3 patients per day have various types of ultrasound exams, in addition to the 40-50 patients undergoing radiographic examination.

There is no permanent radiologist, and when no volunteer radiologist is present, the ordering clinicians interpret their own exams. There are four full-time radiologic technologists and one chief technologist, all of them Haitian. They have no formal training, but have learned their radiography skills through apprenticeship.

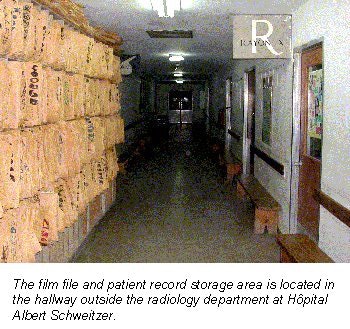

Intermittently, volunteer radiologic technologists spend short amounts of time in the department providing valuable expertise and assistance with the clinical workload. No clerical staff is available, so technologists are responsible for matching the x-ray request with the appropriate patient’s film jacket, and then filing the completed exam after it has been interpreted. Both the film storage shelves and the patient waiting area are located in the hall just outside the radiology department.

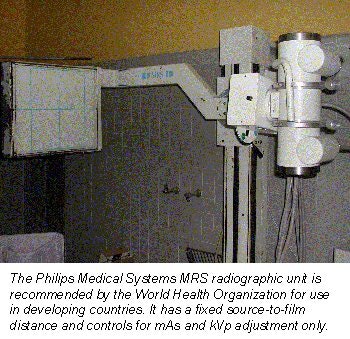

There are two dedicated radiography units in the department, including a Philips MRS (Multi-Radiography System, Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) and a newly installed Summit Nova 325 EXT Linear 1 unit (Summit X-Ray, Gardena, CA). The department also has two portable units, a functioning UX Universal Uni-matic 325 unit and a nonfunctional GE unit. The dedicated radiography units were also nonfunctional when I arrived. The MRS unit was plagued by a problem with its power supply, and the single-phase Summit unit couldn't be operated due to the generator-damaging power surges it created when in use.

The result was a single operational portable x-ray unit that produced marginal images that are prone to underpenetration and technical inconsistencies. During the first week in February, the hospital received the batteries for the uninterrupted power supply that had been ordered for the MRS unit, and a team of U.S. and Swiss engineers repaired it successfully.

The hospital ultrasound machine is, by design, a portable system (Logiq Alpha 100, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) but is currently being used as a stationary unit. The unit is under constant lock and key due to the high risk of theft. It has two curved-array transducers (3.5 and 5 MHz) and provides good-quality gray-scale images but lacks color Doppler or power Doppler and does not have linear, transthoracic, or intracavitary transducers.

The radiology exams are very affordable, even by local standards. The patient charge for a general radiographic examination is 10 gourdes (43¢) and 25 gourdes ($1.08) for exams using barium or intravenous contrast. Surprisingly, ultrasound examinations are looked upon as part of the clinical assessment and are done free of charge.

The hospital’s charges for these examinations have not changed much in the past two decades, and the average charge, when adjusted according to the differences in average annual income, would be about $52 for the vast majority of the x-ray examinations (average annual income in Haiti is about $250).

Radiology experience

The daily schedule begins at 7 a.m. with a morning conference in the hospital library. What's unique is that the meeting is truly multidisciplinary, and includes physicians from all specialties, nurses, the chiefs of pharmacy and the laboratory, the hospital director, the director of nursing, and social services.

Three days a week the morning conference is scheduled as an x-ray meeting, where various interesting cases are presented to the group and discussed. The physicians are mostly European and American. Some are short-term volunteers visiting for a few days or weeks, and others are there for periods of 1-2 years or more. There is also a periodic influx of visiting subspecialty teams.

In late January and early February, short-term visits were made by a gastroenterology team from Pittsburgh, an orthopedic surgery team from Atlanta, and a cardiology team from Boston who donated their time, expertise, and some of their equipment to the hospital. The morning conference is always replete with lively discussion and clinically focused debate. Its multidisciplinary composition is effective for reinforcing the importance of the various hospital services needed for effective patient treatment. A spirit of teamwork pervades both clinical and nonclinical activities.

After the morning conference, rounds begin at 8 a.m., with many individuals from the conference joining the clinicians while patients are seen and discussed. Daily rounds start on the adult medicine ward adjacent to the TB isolation section. Typical cases include typhoid fever, marasmus, and various manifestations of HIV, as well as occasional cases of anthrax, rickets, and syphilis. Tuberculosis is endemic in Haiti, and many cases are seen daily. Pulmonary TB is also notorious for heralding the presence of HIV infection.

The visiting staff, mostly from teaching institutions in the U.S. or Europe, often find the cases unusual, and visitors are shocked by the incredibly high prevalence of disease. However, they quickly become accustomed to the new environment and feel comfortable in generating various treatment suggestions.

The Haitian medical staff possesses excellent physical examination skills and thorough practical knowledge of local disease processes. The combined-team process, involving physicians from Haiti, Europe, and the U.S., is not only interesting and educational, but the benefit to the patients from this collaboration is obvious to all involved.

The benefits of ultrasound

During morning rounds, ultrasound requests are compiled and the examinations are begun shortly after the end of rounds. Although the institution’s hospital unit is portable, it remains in a particular room under lock and key. This location is immediately adjacent to the outpatient clinic, making it ideal for same-day examinations on clinic patients, but the room’s small size and lack of a holding area make it very difficult for ultrasound exams to be done on inpatients.

During my time at HAS, we used a small handheld unit (SonoSite 180, SonoSite, Bothell, WA) which was very useful in providing bedside ultrasound services. The unit was small, battery powered, and well-suited for scanning both the inpatients and the ICU patients. Patients were always very polite and cooperative during ultrasound examinations, even when in tremendous pain.

One of the amazing aspects of pediatric ultrasound was how accommodating the children were during exams. Even small children would lie quiet and still while the ultrasound was being done, and the mothers would stand away from the bedside. A startling array of unusual and very advanced disease was seen, including long-standing tuberculous pericarditis, kwashiorkor, and a very high rate of post-partum cardiomyopathy (estimated at 1 in 300 pregnancies). The significant presence of malaria made splenomegaly ubiquitous, and tuberculous peritonitis was the presumed cause of adult ascites until proven otherwise.

After completing the morning ultrasound schedule, the morning x-rays are interpreted in the reading room located in the department. There are usually 15-20 cases from the morning and the night before. There is one radiologic technologist on call, but the vast majority of the films are taken during the day and early evening. Stat films are available but are rarely obtained, and ultrasound is almost never done after hours.

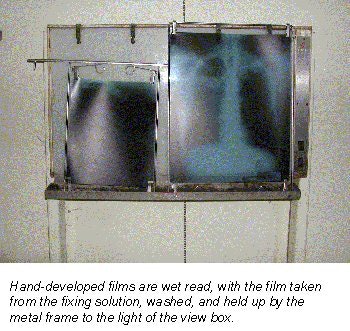

There is no automatic processor; films are hand-developed and dried in a metal box attached to a heated fan. When stat reads are requested during the day, it is literally a wet read, with the film taken from the fixing solution, washed, and held up by the metal frame to the light of the view box.

The films are generally of fair-to-poor quality, primarily due to mismatched screen-film combinations, the use of a portable x-ray unit, and artifacts created by the fan during the development and drying process. Most of these hindrances are unavoidable, so we found it helpful to take an optimistic view of the exam, looking to see what could be seen rather than what couldn't.

The diagnostic capability of the department is also augmented by the availability of ultrasound. However, even though the unit is functional, produces reasonable-quality images, and has proven itself to be durable, it is dramatically underutilized. Without professional scanning and interpretative services the underutilization is not surprising, but the potential benefits that could be realized with an active ultrasound service are substantial.

When sonographic scanning and interpretative services were readily available for both outpatients and inpatients, the volume increased 10-fold, up to 20 or more cases daily. Inevitably, the pathology yield from these examinations was substantial and unexpected diagnoses were common.

Even with the added availability of cross-sectional imaging and the increased workload, scanning went quickly and the tempo of the daily work was comfortable. The thin Haitian patients were ideal subjects for ultrasound, and their cooperative nature made the studies quick and pleasant.

Summary

Haiti is much less seen that it is experienced. The signs of chronic suffering are everywhere in the hospital. The pediatric wards are unusually quiet; many have learned that crying usually won't lead to resolution of their anguish. The obvious malnourishment of some of the children seems to magnify the impact of the situation.

Patients are faced with incredible hardships, and often walk for hours to the hospital, or literally carry family members dozens of miles over rocky mountainous terrain to HAS, all the while understanding that their chances of being seen are poor if they live outside the district served by the hospital. The stark images of the patients who are turned away, the look of misery in their faces, and the reticent acceptance they display are permanently etched in the memories of those who have witnessed them.

In light of the harsh realities the facility faces -- incredible need, limited national infrastructure, and limited financial resources -- Hôpital Albert Schweitzer is making remarkable progress in providing healthcare and community development to the people of eastern Haiti. Its success is attributable in large part to the professionals who donate their time and efforts to HAS, and their dedication to providing high-quality care despite an adverse practice environment. Through their personal effort and dedication, the quality of care delivered by the hospital is the best in Haiti, and the medical staff consistently demonstrates remarkable resourcefulness, making the most of limited resources.

The radiology practice itself is extremely rewarding as patients are compliant, very cooperative, and are immensely appreciative of the services that are provided. The value of the diagnostic imaging component is self-evident as case after case of unbelievable pathology is reported. The addition of ultrasound performance and interpretation expertise provided a service of detection and diagnosis that had not previously been available, and again emphasized the substantial value of cross-sectional imaging in the developing world.

Providing healthcare can be challenging even in developed countries. Yet the experience at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer has proved that high-quality care can be found even in an environment that is uncompromisingly Third World. Visiting personnel have a broad range of reasons for choosing to contribute, but they all point to broadened perspectives as a common element that enriches their experience.

Regardless of whether that experience is for a few days, a few weeks, or a few years, to volunteer time is to commit to a process that will surely alter one's perspective, and potentially one's life. There aren't many places in the world where the value is higher for the work provided, and regardless of one's motivation for making the trip, an excursion to Hôpital Albert Schweitzer is an experience that will live long after the return flight has landed in Miami.

By Dr. Douglas P. BeallAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

April 3, 2001

Special thanks to Cam Pollock and SonoSite for graciously loaning me their handheld SonoSite 180 ultrasound unit.

Links

Friends of Hôpital Albert Schweitzer

Related Reading

Radiology in the shadow of Kilimanjaro, April 17, 2000

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com