Can revisiting forgotten x-ray coils, tubes, and blueprints help radiology better stand on the shoulders of its early giants? Yes, according to a Florida machinist and engineer: In addition to honoring pioneers, rediscovering antique imaging technologies could shed old light on new problems.

"So many patents were filed at the turn of the century, but only a few of the brilliant machines actually were ever mass-produced or preserved," said Jeff Behary, a collector and historian of early x-ray devices.

"There is a good chance a lot of great engineering was in the wrong place at the wrong time," he said. "Right when you think you've seen it all, you find another early book filled with apparatus and experiments that were never published elsewhere. The old texts are like treasure chests."

Behary has been studying antique x-ray machines for more than a decade, researching items, replicating experiments, and generally searching far and wide for lost pieces of x-ray history.

"For the very rare items, it becomes like an archeological dig, and in the case of our most prized possessions, it took more than 10 years to find them," he said.

The search for early systems

An avid collector in general, Behary first began studying antiques labeled as "quack" devices, which he would take apart or repair to determine whether they were legitimate, he said. As he started to examine a wider variety of devices, he found early x-ray machines, in particular, to be the most interesting. "Whether studied from a mechanical or electrical engineering perspective, they were spectacular on all accounts," he said.

Building a reproduction of an apparatus allows him to replicate early techniques, as well as evaluate theories about turn-of-the-century devices, he said. Another purpose is to learn more about the early inventors themselves: One of the first to pique his interest was Thomas Kinraide, an inventor who provided important advances in high-frequency coils and x-ray systems, according to Behary.

|

| Original Kinraide coil for alternating currents. All images courtesy of Jeff Behary. |

|

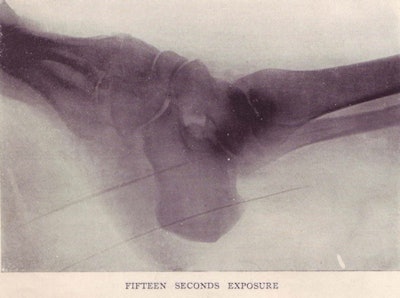

| Scan from a 1901 Kinraide coil catalog from Swett & Lewis Company, which manufactured the coils. Recommended exposure times, according to the booklet, included three minutes for the chest, 15 seconds for the ankle, and five minutes for the pelvis. |

"Kinraide took the concept of the induction coil and over the course of several years reduced the amount of wire from over 20 miles to less than 1,000 ft," Behary said. "The unusual configuration and concepts in his machines were important historically because he was the first to commercialize ideas that would become common in the decades that followed."

"Many portable x-ray machines decades later follow his general process, and the same configurations were used in wireless telegraphy during World War I," he said.

In one of his first attempts at replicating Kinraide's work, Behary found that the flat induction coil he built had an unexpectedly high output given its size (12 x 24 x 4-inch box, with two insulated posts protruding from the top). The 2-kW system -- built with materials such as copper, beeswax, and tungsten -- could produce a 1-ft span of electricity, using less than 1 lb of wire. The replication has intrigued high-voltage engineers because of the unique, forgotten coil geometry utilized, he said.

|

| Discharge from recreated Kinraide device. |

In addition to reproductions, originals by Kinraide are among the notable items Behary has collected. In closed-off rooms beneath Kinraide's former Massachusetts home, Behary and his wife discovered his laboratory, hundreds of glass plate negatives of electrical discharges, early Tesla coils, and apparatus used to image the entire human trunk, environmentally damaged but otherwise untouched for a century.

|

| Electric discharge photograph from the collection of glass plate negatives found at Kinraide's home. |

Other collected items include more than 6,000 hand-drawn blueprints of surgical and x-ray apparatus from the 1920s through the 1940s, given by the former H.G. Fischer & Company (Fischer was the founder of radiography and mammography vendor Fischer Imaging), and an 1868 Ritchie induction coil. The induction coil by Edward Ritchie was the 12th made and is likely the oldest spark coil in the U.S., according to Behary.

"Ritchie's invention, though 28 years before the discovery of the x-ray, proved to be one of the most valuable tools in the early x-ray field," he said.

|

| No. 12 1868 induction coil by Edward Ritchie. |

Lessons from the past

While the history of x-ray apparatus is interesting in its own right, it also contains lessons that might be useful for those in radiology today. In fact, some of the advances we think of as relatively modern actually originated at the turn of the 20th century, Behary said.

For example, the intensifying screen patented by Kinraide in 1897 allowed exposures in less than a minute, even using ancient emulsions and gas x-ray tubes, he said. And Dr. William Rollins, a dentist, physician, and fellow New England inventor, was an early proponent of x-ray protection measures -- an issue that's certainly taken center stage of late.

"Rollins designed safety housing, [safer] fluoroscopes, and protective wear as early as 1898, yet much of these precautions were ignored until it was too late," Behary said.

Early apparatus also contain engineering clues that could help modern systems achieve smaller, more efficient design.

"Most machines still have a large high-voltage transformer, which still contains miles of wire and a hernia's worth of steel laminations, not to mention a few gallons of mineral oil," he said. Attributes of the early portable machines, such as more efficient coil design, could perhaps be combined with modern materials, producing lighter, smaller, and cheaper-to-build systems.

The multifunctionality of early machines also is important, Behary noted. Early x-ray systems often had additional electrical outputs for features such as diagnostic lamps, hot cautery knives, and various electromedical modalities. For surgical use, they also contained suction and vacuum lines, with some of the compressed air being diverted for cooling purposes, allowing the system to function longer, he said.

"These additional modalities were not cumbersome to the devices, as they were all introduced into the existing circuitry as clever engineering modifications," he said. "Some of these multifunction machines were only the size of a small suitcase, yet they provided the physician with the equivalent of a whole office of apparatus."

"A machine like this could be made inexpensively and marketed for physicians and surgeons abroad who do not have the luxuries of space or are operating on limited funds," he said.

Behary collaborates with several other collectors worldwide to preserve and promote understanding of antique x-ray systems, he said. His collection, the Turn of the Century Electrotherapy Museum, can be viewed in person or online, including images and video.