This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology, written by Dr. Howard Forman, associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS).

In this brief I will explore the dual eligibles program. The federal government, in crafting Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, recognized that Medicare alone might not provide enough assistance for the poorest and sickest elderly. By modifying the benefits of Medicaid and combining it with Medicare, a seemingly new program for dual eligibles was born.

The dual eligibles are a very different group of citizens with extremely high healthcare needs and unique attributes. Almost 7.5 million Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries are dual eligibles. This label is appropriately descriptive, but fails to convey the special needs and features of this population.

As we have discussed in prior briefs, eligibility for Medicare includes being either disabled or elderly. Eligibility for Medicaid, on the other hand, requires very low income and minimal assets. Thus, one might think that a dual eligible would merely be the intersection of these two groups, with no particular coincident features. Such an assumption might be correct if not for Social Security payments. Most elderly (and most disabled) receive Social Security payments and those payments may exceed Medicaid eligibility requirements. Further, most individuals have some assets and, thus, are ineligible for Medicaid.

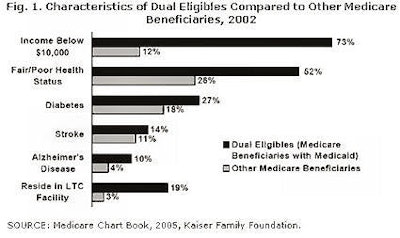

What is it, then, that propels a person to be a dual eligible? The two colliding factors are poor health and poverty. Together they represent an insurmountable challenge for most people and families. Thus, the dual eligible program is critical to the U.S. safety net. Figure 1, below, demonstrates the unique characteristics of the dual eligible population as compared to the traditional Medicare beneficiary.

Medicare provides basic health services, including physician and hospital care, but (until now) has not provided for prescription drugs. Further, the co-pays, deductibles, and premiums can represent an enormous expense for an individual (a single hospitalization would generally require at least $2,000 in out-of-pocket expenses for the first day of admission, inclusive of 12 months of premium payments and the hospital deductible, without consideration of professional fee co-pays). For the most needy dual eligibles, Medicaid will pay the Part B premium ($87+ per month in 2006). It pays for most cost-sharing with Medicare (including the deductible for Part A) and provides additional uncovered benefits such as dental care, vision care, and until 2006, prescription drugs.

|

There are really two main groups of dual eligibles: those with full coverage (6.2 million) and those who receive some assistance (numbering 1.3 million). Dual eligibles are higher-volume/higher-need users of all Medicare services. Total healthcare costs are typically twice the level of traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Medicare covers approximately 43% of the total costs, with Medicaid covering 38%.

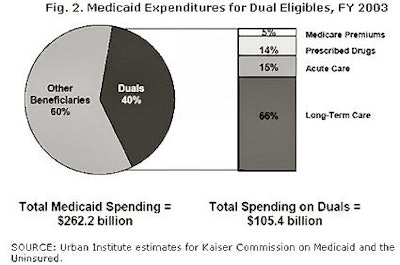

This still leaves these beneficiaries with 19% out-of-pocket costs. Dual eligibles actually represent the single largest share of Medicaid spending (40%), and the majority of these expenses (66%) are for long-term care. Figure 2, below, summarizes the breakdown of current dual-eligible spending.

|

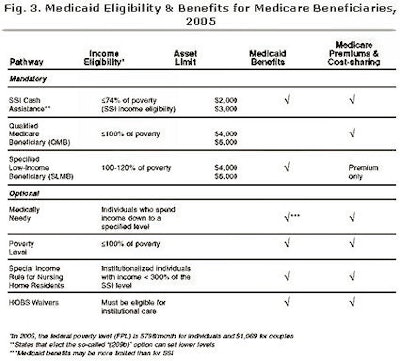

Qualifying as a dual eligible is not obvious to many people. It is not merely an income test, but also an asset test that one must pass. Further, definitions of income are different for qualifying for Medicaid than one might discern from a tax form.

Medicaid income eligibility includes all forms of income, irrespective of tax treatment. Still, there are different pathways to eligibility as shown in Figure 3. For Medicare beneficiaries who are above the federal poverty level, Medicaid's assistance is more limited but still important.

Does this program really affect us as radiologists? As with many policy issues the answer is complex. Medicaid is a federal- and state-funded program that is already a tremendous drain on state budgetary resources. We have previously discussed the fact that there are many optional populations in Medicaid. In tight budgetary times, these populations may get dropped. To the extent that the dual eligibles crowd out these groups, the ranks of the uninsured may grow.

While many of us find it disheartening that 45.8 million people in the U.S. are without health insurance and this number could continue to grow, we should take pride in the fact that the U.S. provides for its least fortunate and most vulnerable citizens. It would be unconscionable for us to leave our poorest and sickest elderly without access to necessary health services.

In a future brief, I will provide an update on the State Children's Health Insurance Plan (SCHIP), a program that has become a critical third leg on the stool of healthcare safety net programs, particularly for U.S. children. The SCHIP program is relatively inexpensive and provides healthcare financing for many otherwise healthy, but poor, children in every state.

By Dr. Howard P. Forman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

December 22, 2005

Dr. Forman is an associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology (December 2005, Vol. 185:6). Reprinted by permission of the ARRS.

Related Reading

Government response to escalating imaging costs, December 12, 2005

BEIR VII and separating fact from fear, November 18, 2005

Medicaid cuts and radiology's quandary, September 13, 2005

MedPAC, Medicare, and imaging growth, August 16, 2005

Medicare's condition in 2005: critical, June 15, 2005

Copyright © 2005 American Roentgen Ray Society