This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology, written by Karl Muchantef and Paul G. O'Brien, guest editors of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS).

Why is the Canadian health system worth considering? U.S. interest in Canadian Medicare often reflects the challenges to the American system. In the 1970s, with the U.S. Congress considering national healthcare proposals, the Canadian system drew consideration. Interest subsequently waned until the early 1990s, when comprehensive health system reform was high on the federal agenda. Now, the growing sense of need to address employers' healthcare costs as well as predicted strains to the financial underpinnings of U.S. Medicare form the backdrop for American interest in Canadian healthcare.

The origin of national healthcare in Canada dates back to 1957. The federal government at the time, under the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, promised cash transfers to any province providing its residents with a universal insurance scheme offering first-dollar coverage of hospital care and related diagnostic services. In 1968, the program was expanded to include medical insurance, again offering cash transfers to provinces who insured their residents for both hospital and medical care. By 1971 all the provinces were participating in the program, which came to be known as Medicare.

Through the 1970s provincial governments fought to suppress burgeoning healthcare costs by, among other means, depressing physicians' pay. A number of practitioners responded by levying user fees directly to patients above and beyond fees received from public funds. The federal government countered in 1984 with the Canada Health Act, which consolidated previous health insurance legislation and also reduced federal transfers to provinces that permitted user fees. Despite fervent protests by medical practitioners, each province enacted provincial legislation putting an end to the additional charges.

The Canada Health Act endures still. Its five cornerstone conditions continue to shape provincial health insurance programs: universal coverage for all provincial residents on uniform terms and conditions; comprehensive coverage of all necessary physician and hospital services; access to insured services without charges; public not-for-profit administration; and portability of coverage for travel within Canada.

Each Canadian province is thus responsible for ensuring the hospital and medical care of its residents. Provincial governments establish health insurance programs as they see fit; however, these programs must conform to the federal standards in order to receive federal funding support. Unlike in the American system, the federal government is not directly involved, with few exceptions, in the compensation of physicians or hospitals.

To preclude the creation of a two-tiered healthcare delivery system, private insurance for necessary services has in effect been banned. Part of the thinking here is that a second, private tier might not supplement the public system but could detract from it. Private healthcare might draw the best clinicians away from the public sector. Also, better care and first access to costly facilities such as MRIs, operating room time, and hospital care would be available to those who pay for it, with the remainder falling to the public sector. No provincial healthcare scheme impedes a patient's free choice of clinics, hospitals, or physicians.

Although Canadian healthcare uses public mechanisms to pay for physician and hospital services, the system relies on private delivery of those services. The majority of medical practitioners, including radiologists, continue to be paid on a fee-for-service basis. They are autonomous small-business owners remunerated for each service by provincial ministries of health. This avoids saddling governments with the responsibility of organizing clinics and hospitals. Physicians generally own or lease the office in which they work, and the fees they receive from government include compensation for professional and facility resources.

In short, Canada has adopted private delivery of physician and hospital services while insisting on public funding to maintain equity. Healthcare in Canada is thus not socialized medicine, but rather a form of socialized insurance. Canadian Senator Michael Kirby, chair of the Senate committee on health care, stated that it is a "great myth of Canadian public life" that the Canada Health Act prohibits private delivery of health services (Canadian Medical Association Journal , January 18, 2005, Vol. 172:2, p. 167).

"There has never been a legislation that says who can deliver service. The rule has been those services must be publicly financed, but anybody could deliver -- as long as you were not extra-billing," he stated.

The Canada Health Act, as described above, provides for physician and hospital care. Other goods and services -- home care, nursing homes, outpatient pharmaceuticals, optometric, and dental care -- are financed by a mix of private and provincial funds. For these services, provincial funding is offered only to some population groups, with various income-related eligibility requirements and copayments. Moreover, provincial programs vary widely in the extent of coverage and the terms for access.

So when considering the full scope of healthcare, Canadian financing arrangements can be thought of as a set of three concentric circles (Health Affairs, May/June 2002, Vol. 21:3, pp. 32-46). At the core are services that are exclusively financed through public means: necessary services provided by physicians and hospitals. In an intermediate ring are programs -- such as home care, outpatient pharmaceuticals, etc. -- that receive a mix of public and private funds. In the outer circle are services that receive no public funds. In recent times, policy makers are rethinking what belongs in each circle. Home care, for example, is shifting toward the inner circle as increased public investment in this service is intended to complement a reduction in hospital costs. This illustrates a recent trend in Canadian health policy: that funding arrangements should facilitate clinical efficiency, instead of clinical inefficiency resulting from funding arrangements.

Radiologists are mostly affected by the funding arrangements for physician and hospital services. How does a single-payer system affect Canadian radiologists differently than, say, a U.S.-style system would? To start with, the provincial billing code is a simple one. The process is easily completed and leads to the prompt remuneration of radiologists at the end of each month. In contrast to the U.S., there is no federal legislation that mandates the scrutiny of medical coding and billing practices. Physicians' billing practices are peer-reviewed by provincial colleges of physicians and surgeons and by provincial ministries of health. These organizational arrangements result in substantially lower billing costs for professional services in Canada than in the U.S. (Journal of the American College of Radiology, September 2004, Vol. 1:9, pp. 659-670).

Fee schedules are negotiated annually between provincial ministries of health and physicians' associations. Radiologists in Ontario, for example, are represented by the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) in negotiations held with the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Because remuneration is closely tied to the fee schedules, the negotiations are occasionally acrimonious.

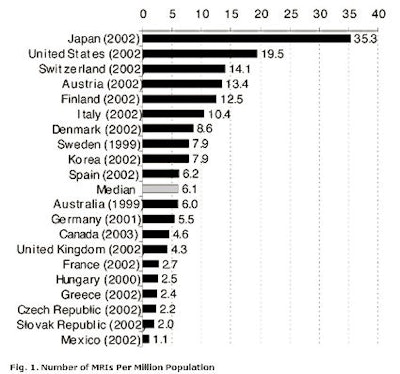

Canada is often depicted in both countries as trailing in medical technology, particularly advanced imaging technologies. Indeed, as we will detail in a future brief, the failure of both provincial and federal governments to commit to consistent and adequate funding for technology acquisition during the 1990s led to the limited availability of technologies such as MRI, advanced CT, and PET. However, recent governmental surplus budgets have resulted in catch-up spending on medical technologies.

In September 2000, the federal government created a Canadian $1 billion ($881 million U.S.) Medical Equipment Fund to help the provinces acquire technologies. In 2003, the federal government provided an additional $1.5 billion ($1.3 billion) as part of the new Diagnostic/Medical Equipment Fund. For radiologists, this has resulted in increased imaging capacity. However, the most recent data available, 2003, show that wait times are not significantly changed, presumably the result of an offsetting increase in utilization. In 2003, the mean wait time was 31 days for a nonurgent CT scan and 47 days for MRI, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information. There is, however, broad geographic variance in wait times across Canada.

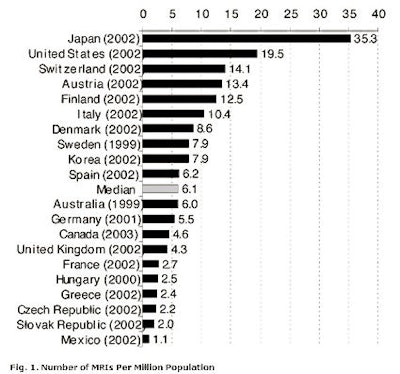

Figure 1, below, offers a perspective on Canada's standing with regards to imaging technology. The figure illustrates the availability of MRI technology in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries. Canada sits slightly beneath the median. This standing results not only from the structure of health finance in Canada, but also reflects political and economic influences.

|

Notes for figure 1:

- Countries for which only data prior to 1999 were available are not shown.

- Mexico only counts scanners located in public institutions.

- Units located both in hospitals and in freestanding imaging facilities are included for Canada.

- Only units located in hospitals and general clinics are counted in Japan.

- U.K. includes data for only England and Scotland.

- Units located both in hospitals and nonhospital sites are included for the U.S. Mobile MRI units are not included. IMV Medical Information Division (Des Plaines, IL) was used as the data source because it counts the number of MRIs, whereas Paris-based OECD figures count the number of hospitals that report having at least one scanner.

Sources: OECD Health Data 2004, OECD National Inventory of Selected Imaging Equipment, and IMV 2004 Information Services for the Health Care and Scientific Markets.

Both in Canada and in the U.S., health policy is continuously evolving. In response to new challenges, policy makers consider and enact change. These decisions are not made in a vacuum, but are guided by national priorities as well as international experience. The Canadian experience illustrates a possible implementation of a single-payer health insurance system. Radiologists, as providers and occasional recipients of healthcare, have a great stake in how healthcare policy develops and how it impacts access, efficiency, technology adoption, and the quality of care in general.

In the next policy brief, we will discuss the strengths and vulnerabilities inherent in a single-payer healthcare system.

By Karl Muchantef and Paul G. O'Brien

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

May 16, 2006

Muchantef and O'Brien are guest editors of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology (April 2006, Vol. 186:2). Reprinted by permission of the ARRS.

Related Reading

Offshoring, teleradiology, and the future of our specialty, March 20, 2006

M.B.A. education for physicians: cross-training options, January 25, 2006

Dual eligibles: Rarely mentioned, critically important, December 22, 2005

Government response to escalating imaging costs, December 12, 2005

BEIR VII and separating fact from fear, November 18, 2005

Copyright © 2006 American Roentgen Ray Society

Disclosure notice: AuntMinnie.com is owned by IMV, Ltd.