This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology, written by Karl Muchantef and Paul G. O'Brien, guest editors of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS).

Single-payor virtues

A publicly administered universal health insurance system is a form of public policy. In this regard, Canadian Medicare achieves certain social objectives adeptly.

First, the administrative efficiency of the single-payor system is well known. In an illustrative comparison of a Toronto hospital versus one of equal size in Boston, the Toronto hospital had 17 employees in the billing and collections department, while the Boston hospital had 317.

Second, the single-payor system can be remarkably nimble. From 1993-1997, a profound transformation in the Canadian hospital sector was achieved. Driven by fiscal pressures and new medical technologies, the number of hospital beds in Canada was decreased by 21%. Over the same period, public spending on home care was increased by 80% to help move the location of care away from expensive inpatient acute facilities. In a short time, healthcare functional arrangements were transformed.

Third, Canadian Medicare provides a competitive advantage to Canadian employers in that it greatly reduces the burden of providing employee health insurance. Conversely, workers are freed from having to choose one job over another based on insurance for necessary care. Social health insurance is thus a public program that also benefits the private sector.

Fourth, healthcare, like most other things, is characterized by diminishing returns. Mechanisms that distribute care according to need instead of wealth help to promote the greatest good, instead of furthering the advantage of some. It is debatable whether healthcare is a privilege or a right of citizenship, but treating healthcare as a public resource and distributing it equitably enhances the effectiveness of the available healthcare resources.

Fifth, universal insurance creates a common interest. Because all Canadians share the same healthcare lot, every member of the population has an interest in preserving the quality of publicly available care. A two-tiered system could diffuse the political will to preserve quality care for everyone.

Sixth, the majority of Canadians feel that there is ethical value in the equitable distribution of healthcare. This is the feature that proponents of Canadian Medicare tout most often, to the frequent exclusion of the other six.

Single-payor vulnerabilities

Unfortunately, single-payor healthcare also has vulnerabilities that stem from and are inseparable from the same elements that constitute its strengths, particularly the first two strengths listed above.

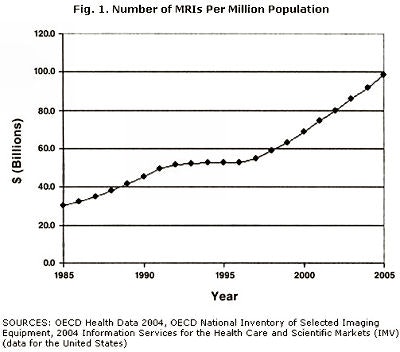

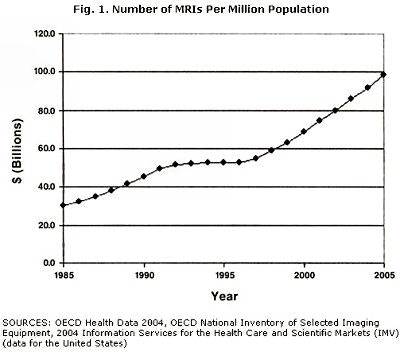

The first great vulnerability of single-payor health care is economic. With a single payor, any financial strain on the payor can be transmitted throughout the whole system. In Canada, this was most recently demonstrated in the period from 1993-1997. Motivated by mounting debts and an aversion to deficit spending, governments reduced financial commitments to healthcare. The fallout from this policy is well known: a decrease in the number of hospital beds, lengthy wait times for elective surgery, limited adoption of state-of-the-art imaging technologies, and delays in replacing aging imaging equipment.

Figure 1, below, illustrates the constraint of public healthcare spending between 1993 and 1997, as well as the ensuing spending surge. The short-term savings amounted to about $30 billion Canadian ($27.2 billion U.S.), but the savings came at a great cost to health policy. Canadians' confidence in their health infrastructure ebbed. Federal-provincial talks became acrimonious, with each side faulting the other but neither side enacting change. Public debate increasingly called for libertarian policies to raise funding levels, suggesting that it was better to abandon the current health insurance scheme than to strengthen it.

|

A recent court decision has heightened the debate. Historically, private health insurance for publicly funded services was banned to preempt the rise of a two-tiered system. In June of 2005, Canada's Supreme Court ruled on a case involving a Quebec patient who had waited nearly one year before receiving hip replacement surgery. The Supreme Court found that waiting times had become unreasonably long, that some patients suffered considerably, and that some experienced deterioration of their conditions while awaiting care. The court ruled that failure to provide publicly funded care in a timely manner while denying access to private insurance constituted a violation of the Quebec Charter of Rights and Freedoms' provision guaranteeing the right to personal inviolability. Although the ruling applies only in Quebec, the decision may to lead to similar legal challenges in other provinces.

It is not yet clear how this decision will impact Canadian health policy. One of two outcomes will likely result: Governments will either heighten spending on healthcare in order to reduce wait times; or they will alter legislation and allow private insurance. While there are advocates of each solution, national polls suggest that popular sentiment is in favor of preserving single-tiered health coverage. Events will be influenced, of course, by the federal elections in January 2006, which replaced the liberal government with a conservative party and prime minister.

That political influence can fundamentally affect health policy constitutes the second great vulnerability of Canadian healthcare. Government-run health insurance is subject to the ideological influence of the party in power. Some conservative provincial governments are permissive toward a second tier of services accessed through private funds. The leading province in this regard is Alberta, where the conservative government of Ralph Klein has held power since 1993. Klein has endorsed policies that conflict with the character of Medicare, such as instituting health insurance premiums, and providing "enhanced" medical service to those who pay for the privilege.

Arnold Aberman, former dean of the University of Toronto medical school, expresses perhaps the most damaging argument against universal healthcare.

"(Canada should) decriminalize medical acts between consenting adults and allow patients to purchase more medical care than the government provides," he said.

Other critics of the Canada Health Act note that two-tiered healthcare already exists: Studies have shown that access in Canada is influenced by wealth, with well-to-do Canadians receiving proportionately more ambulatory specialist care and preventive services. Further, some Canadians already access healthcare privately by crossing the border into the U.S. At times, provincial governments have even used American health resources as a safety valve, shipping patients to the U.S. for care not locally available in a timely fashion.

The virtues and vulnerabilities outlined above are features inherent to a single-payor health system. The realities of healthcare delivery in Canada reflect these virtues and vulnerabilities, as well as the political, economic, geographic, and cultural circumstances particular to the country. The challenges to Canadian Medicare -- wait times, staffing shortages, etc. -- are not purely the result of the single-payor system, but also reflect the Canadian implementation of one such scheme. Fifteen years ago Medicare was the apple of Canada's eye. Economic and political conditions in Canada during the 1990s played into the vulnerabilities of single-payor healthcare, and Canadian Medicare is still recovering.

For practitioners in the U.S., interest in Canadian healthcare is mitigated by the dilemmas facing that system. With healthcare costs in the U.S. near 16% of gross domestic product (versus 10% in Canada), with administration consuming about one-third of healthcare dollars, and challenges to the future funding of current U.S. Medicare arrangements, tapping the virtues of a single-payor insurance program seems like an option worth considering. It is one that is occasionally proposed. When considering that tack, the Canadian experience should be viewed as an implementation, not the necessary result, of a single-payor approach.

Guiding health policy in both Canada and in the U.S. is a matter of constant navigation and reorientation. At stake for radiologists in both countries are the source of personal income, personal as well as professional access to imaging equipment, the administrative complexity of our practices, access for our patients, and the financial effect we have on our patients, to name more than a few. Our policy makers often look for international solutions to national problems, and the decision to accept or ignore these possibilities affects us all.

By Karl Muchantef and Paul G. O'Brien

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

July 4, 2006

Muchantef and O'Brien are guest editors of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology (May 2006, Vol. 186:5). Reprinted by permission of the ARRS.

Related Reading

Offshoring, teleradiology, and the future of our specialty, March 20, 2006

M.B.A. education for physicians: cross-training options, January 25, 2006

Dual eligibles: Rarely mentioned, critically important, December 22, 2005

Government response to escalating imaging costs, December 12, 2005

Copyright © 2006 American Roentgen Ray Society

Disclosure notice: AuntMinnie.com is owned by IMV, Ltd.