This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology, written by Dr. Howard Forman, associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS).

In 2005, the Medicare program covered 42.5 million people: 35.8 million age 65 and older and 6.7 million disabled individuals. Total benefits paid were $330 billion, with an additional $6 billion spent on program administration. The fund took in $357 billion in income (premiums and taxes). The trust fund (Part A-Hospital Insurance) held $310 billion in assets (treasury securities).

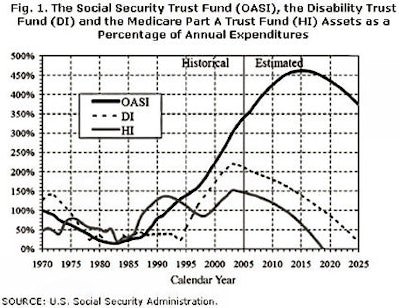

The Part A trust fund is already in the early phases of exhaustion, as illustrated in figure 1, below. This graph demonstrates the currently projected future path of the three major government trust funds: the Social Security Trust Fund (OASI), the Disability Trust Fund (DI), and the Part A Trust Fund (HI). Despite recent concerns in Washington, DC, regarding the OASI/Social Security Trust Fund, we see that this fund is actually in reasonable shape for the next few decades.

|

On the other hand, the Medicare Trust Fund is projected to extinguish at the end of the next decade -- 2018, by current estimates. The savvy reader will notice that the fund appeared to be in similar straits 10 years ago, and not only survived longer than expected, but seemed to rally. This noticeable improvement in the prospects of the trust fund was wholly due to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which dramatically reduced reimbursements to providers and, thus, reduced the cost growth in the program. This one-time event did help the trust fund, but is unlikely to be replicated; as it stands, many of its longer-term effects are still being felt with reduced nursing levels and capped graduate medical education funding for our residents and fellows.

The only solutions to the Medicare Part A financial debacle are increased taxes or decreased benefits. I do not believe our nation or its representatives will raise taxes sufficiently to truly fund the program appropriately; the program's future will be dictated, instead, by some combination of reduction in benefits and increased taxes. What form will "benefit reduction" take?

It has not seemed politically feasible to increase the age of eligibility for Medicare (despite the fact that it no longer coincides with the eligibility age for Social Security, now being adjusted upward to 67). The reality is that the near elderly are already some of the most uninsured members of society. It also seems unlikely that we will see a true reduction in covered services. Our nation is not quite ready for explicit rationing of medically necessary services. In all likelihood, then, we will see increased cost-sharing and, perhaps, some degree of income testing for receiving full benefits.

A solution need not solve the long-term problem; it just needs to advance it enough to get through the next few decades. As Section 801 of the Medicare Modernization Act makes clear, Congress will be forced to act by 2007, since the program is rapidly approaching the legislatively determined magic figure of 45% (this being the difference between Medicare's total outlays and its "dedicated financing sources").

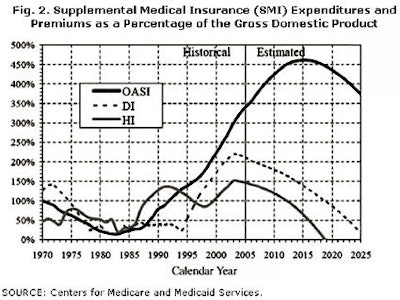

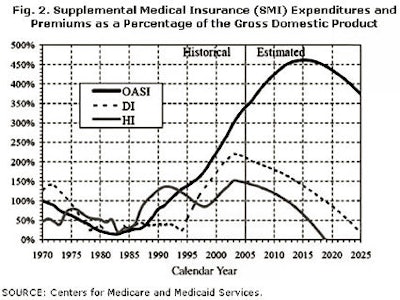

Figure 2, below, looks at the financial solvency and sustainability of the Part B (Supplemental Medical Insurance) and Part D programs. These two programs are often considered together since their financing is from general government revenue, rather than from a discreet tax and trust fund.

|

On the one hand, this situation makes the solvency of these programs certain. As long as the government exists, it must, by statute, fund these programs. It cannot go bankrupt. On the other hand, it is quite clear that the funding is currently projected to grow at an extraordinary rate, almost certainly mandating an increase in the tax burden, national debt, or both.

Further, it does not even account for another product of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997: the so-called "sustainable growth rate" (SGR) legislation, which currently projects that physicians will receive 5+% annual reductions in fees for as far as the eye can see. Since most of us realize that this would mean a breakdown in Medicare beneficiary access, we know it will not actually occur (at least not to that degree). However, any solution will make the total expenditures of the Part B program that much greater and worsen the financial burden on our nation.

It should not be lost on the reader that the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (signed by President Bush in January of this year) targeted Medicare for savings, almost entirely shouldered by our profession. This midnight attack on the fees paid to outpatient imaging practices has yet to be felt, but it may just be the first salvo in a war on the obvious increases in imaging expenses by the Medicare program(s).

There is no magic bullet that will save us from reductions in benefits or higher tax rates. On the other hand, relatively small adjustments made sooner rather than later can dramatically improve the prospects for this important government program. As I have also indicated in past briefs, the introduction and expansion of Medicare Advantage (or Managed Medicare, as it has been called in the past) may reduce the financial strain on both parts of the program. Further, we have yet to truly realize the changes that will occur as a result of the introduction of the Medicare drug benefit. This program, as advertised, may reduce other health services demands and may reduce the future financial strains.

As imaging specialists, we believe that our services are critical and justify their expenses. Unfortunately, we are often hidden in dark rooms while our patients receive their services and consultations. This makes us an easier target for reductions in spending. I concur with the many voices who believe we must become ever more vigilant in presenting a public face to the specialty and promoting our good services through evidence-based practice.

By Dr. Howard P. Forman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

July 25, 2006

Forman is an associate editor of health policy for the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS). This article originally appeared in the American Journal of Roentgenology (July 2006, Vol. 187:1). Reprinted by permission of the ARRS.

Related Reading

Offshoring, teleradiology, and the future of our specialty, March 20, 2006

M.B.A. education for physicians: cross-training options, January 25, 2006

Copyright © 2006 American Roentgen Ray Society