Diffusion MR imaging suggests that soccer heading may cause more damage to the brain than previously thought, according to study results to be presented at the upcoming RSNA meeting.

Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD.

Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD.

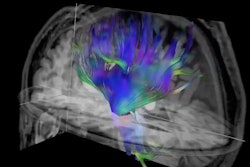

A team of researchers led by senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York reported that diffusion MRI showed microstructural features of injury to the grooved indentations called sulci found in the white matter of the brain of soccer players – an area associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

"The potential effects of repeated head impacts in sport are much more extensive than previously known and affect locations similar to where we've seen chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology," Lipton said in a statement released by the RSNA. "This raises concern for delayed adverse effects of head impacts."

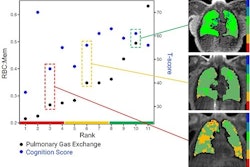

Lipton and colleagues used diffusion MRI to analyze microstructures close to the surface of the brain. They compared brain MRI scans of 352 male and female amateur soccer players, ranging in age from 18 to 53, to brain MRI exams of 77 noncollision sport athletes, such as runners. Study participants underwent 3-tesla diffusion MRI; the researchers tracked diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) metrics from juxtacortical white matter below the sulci.

Overall, the team found that diffusion MRI metrics in the depths of sulci of the juxtacortical white matter in the soccer players differed from the controls in a way that was associated with repetitive head impacts. The investigators reported the following:

- Soccer players who headed the ball at high levels showed abnormality of the brain's white matter adjacent to sulci.

- The abnormalities were most prominent in the frontal lobe of the brain, an area vulnerable to damage from trauma.

- More repetitive head impacts were associated with poorer verbal learning.

"Our analysis showed that the white matter abnormalities represent a mechanism by which heading leads to worse cognitive performance," Lipton said.

Surprisingly, most of the study participants had never sustained a concussion or been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury, Lipton and colleagues noted, which "suggests that repeated head impacts that don't result in serious injury may still adversely affect the brain."

"[Our work] identifies structural brain abnormalities from repeated head impacts among healthy athletes," Lipton said. "The abnormalities occur in the locations most characteristic of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, are associated with worse ability to learn a cognitive task and could affect function in the future."