Tracheobronchomalacia:

Clinical:

Tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) characterized by weakness of the tracheal walls and supporting cartilage, and degeneration and atrophy of the longitudinal elastic fibers which results in excessive airway compressibility and excessive expiratory collapsibility [1,5,6]. It is traditionally viewed as a disorder of infants and neonates, but the condition can be found in up to 5-14% of adults presenting with pulmonary complaints (such as chronic cough or chronic bronchitis) and the incidence increases with advancing age [1,4,5]. The condition can present at birth (a primary or congenital form due to impaired cartilage maturation) or be an acquired lesion associated with prior intubation, long standing extrinsic central airway compression, trauma, infection, or radiation [1,4,6]. A history of a tracheoesophageal fistula is also a risk factor for the disorder [1]. Symptoms in adults include cough, wheezing, and dyspnea- complaints which are often misinterpreted as asthma [1]. TBM also prevents normal clearance of secretions and may lead to recurrent infections [6]. Most infants that are affected outgrow primary TBM by 2 years of age [6]. The disease may be limited to the bronchi in 14% of cases [8].

In patients with severe symptomatic tracheobronchomalacia due to flaccidity of the posterior membranous portion of the trachea, surgical intervention with tracheoplasty can be curative [5]. Following treatment with tracheoplasty, CT can confirm a successful outcome by showing a reduction in the degree of airway collapse [5].

X-ray:

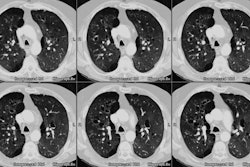

The diagnosis of TBM can be confirmed with expiratory CT imaging [4]. With expiration, the normal trachea demonstrates a mean decrease in cross-sectional area of 35% [1]. In patients with tracheomalacia, the cross-sectional area commonly decreases by more than 50% (and up to 100%) [1,2]. Airway collapse can be better seen on dynamic CT imaging because dynamic expiration produces a higher level of intrathoracic-extratracheal pressure compared to end-expiration [4]. In fact, more than 50% of cases of TBM may not be detected if dynamic expiratpry imaging is not performed [4]. For the dynamic study, image acquisition should begin with the onset of the patient's forced expiration [4]. Air trapping is also commonly observed on expiratory images [3].

**Note- that in studies of asymptomatic healthy volunteers, between 73-78% can demonstrate forced expiratory tracheal collapse that exceeds the current diagnostic criteria for TBM [7,8]. Authors now recommend a threshold level of at least 70% expiratory collapse on dynamic CT scans as the criteria for diagnosis of TBM [8,9]. As always- forced expiratory CT findings should be correlated with the presence of clinical symptoms and pulmonary function testing [8].

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 2001; Gilkeson RC, et al. Tracheobronchomalacia: Dynamic airway evaluation with multidetector CT. 176: 205-210

(2) AJR 2003; Hasegawa I, et al. Tracheomalacia incidentally detected on CT pulmonary angiography of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. 181: 1505-1509

(3) AJR 2004; Zhang J, et al. Frequency and severity of air trapping at dynamic expiratory CT in patients with tracheobronchomalacia. 182: 81-85

(4) Radiology 2005; Baroni RH, et al. Tracheobronchomalacia: comparison between end-exiratory and dynamic expiratory CT for evaluation of central airway collapse. 235: 635-641

(5) AJR 2005; Baroni RH, et al. Dynamic CT evaluation of the central airways in patients undergoing tracheoplasty for tracheobronchomalacia. 184: 1444-1449

(6) Radiology 2009; Lee EY, Boiselle PM. Tracheobronchomalacia in infants and children: multidetector CT evaluation. 252: 7-22

(7) Radiology 2009; Boiselle PM, et al. Tracheal collapsibility in healthy volunteers during forced expiration: assessment with multidetector CT. 252: 255-262

(8) Radiology 2010; Litmanovich D, et al. Bronchial

collapsibility at forced expiration in healthy volunteers:

assessment with multidetector CT. 257: 560-567

(9) AJR 2015; Heidinger BH, et al. Imaging of large airways disorders. 205: 41-56