Cost management is essential in all areas of healthcare, and all facilities are being asked to do more with fewer resources. In an increasingly competitive imaging environment, controlling costs while still effectively ensuring worker and patient safety can be difficult. Yet, imaging departments and cardiac catheterization laboratories must balance these critical issues, while providing quality patient care and efficient workflow.

Imaging and cardiac catheterization laboratories also face the additional requirements of healthcare and workplace regulations, especially with issues related to contrast handling and administration. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) are now placing greater emphasis on preventing employee exposure to potentially hazardous bloodborne pathogens through sharps-related injuries in the workplace.

In light of these requirements, healthcare facilities are implementing additional safety protocols and moving toward the use of medical devices and instruments that are engineered for safety, such as retractable scalpels and needleless intravenous systems. Medical product packaging can also offer safety benefits, which can benefit facility management as well.

In the imaging department and cardiac catheterization laboratory, contrast media in polymer containers rather than traditional glass bottles can eliminate the risk of a sharps-related injury and reduce costs through more efficient contrast use, increased patient throughput, and decreased waste disposal costs.

Sharps-related injuries

Sharps-related injuries are a serious concern in healthcare facilities. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each year approximately 385,000 percutaneous injuries are sustained by hospital-based healthcare personnel in the U.S.1 Of these injuries, approximately two-thirds are needlesticks and one-third are caused by other sharp objects, such as scalpels and broken glass. While this accounts for more than 1,000 reported injuries per day, this is actually only part of the problem. Surveys of healthcare workers have found that, on average, less than half of all sharps injuries are actually reported,2-5 which would indicate an estimated total number of such injuries of as high as 600,000 to 1 million annually.

Costs of sharps-related injuries

Sharps-related injuries result in a range of costs to the healthcare system: direct costs for treatment of the injury and any sequela, indirect costs for lost productivity, emotional costs and health risk to the injured worker, and the possibility of lawsuits and increased insurance rates for both the individual and institution.

For direct costs, a single sharps injury typically costs an employer an estimated $2,234 to $3,832 just for screening and initial treatment.6,7 Based on current reporting levels, this means that an average 100-bed hospital will spend $44,000 to $99,000 each year on blood draws and laboratory testing for employee sharps-related injuries alone. For a 700-bed facility, this cost would be more than $500,000 per year.

Many indirect costs are also associated with a sharps injury. One such expenditure is administrative costs involved in the investigation and follow-up of all sharps-related injuries. Following each employee injury, an extensive checklist of issues must usually be addressed. Was the sharp contaminated? Who was the patient? What is the health status of that patient? Could this incident have been prevented? Has this problem been addressed before? Are additional safety measures still required?

Other indirect costs may include emergency department visits, related sick days, salary expenses for replacement workers, professional counseling for workers who are exposed to diseases, the cost of prophylactic medications, and medical treatment for any workers who acquire infections.

A 1998 survey tracked the costs associated with percutaneous injuries to healthcare workers at two hospitals.8 One hospital (hospital A) had 345 reported cases of sharps-related injuries at an average cost of $672 per exposure for exposures that were negative for disease. The other (hospital B) had 594 reported cases with an average cost of $539 per negative exposure. For exposures that resulted in positive disease results and those that required additional follow-up, the costs of laboratory testing, required medications, employee health visits, emergency department visits, and other related costs totaled $1,775 per exposure at hospital A and $1,836 at hospital B (Table 1).

The financial cost can be enormous if an employee contracts a serious infection, such as hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), from a sharps injury. According to the American Hospital Association, one case of a serious infection from a bloodborne pathogen can result in $1 million or more in expenditures for medications, testing, lost time, and disability payments.9

In addition, workers' compensation rates for the hospital and personal insurance rates can increase, and the liability exposure, legal costs, and court settlements can total millions of dollars. The largest known settlement to date of a sharps-injury lawsuit involved an employee at a prestigious medical center in the northeastern U.S. who was infected with hepatitis following a sharps injury.10 In this case, the worker was awarded $12 million.

The emotional costs associated with the fear and anxiety about the potential consequences of an exposure are harder to quantify. For anyone who has ever suffered a sharps-related cut, the initial thoughts are: What did I just catch? What am I going to pass on to my family?

In addition to risks to healthcare workers, sharps-related injuries can also place patients at risk. For example, if a radiologic technologist cuts a finger on the metal ring while opening a glass contrast bottle, it is likely that he or she will simply wash and possibly bandage the cut, then continue with patient care without reporting the injury. If that technologist has a cold or other virus, the patient is now at risk. This can be an especially serious risk if the patient is already immunocompromised.

If polymer bottles are used for contrast media, there is no risk of injury to an employee in a radiology department or cardiac catheterization laboratory from a metal ring or broken glass contrast media bottles.

Regulatory safety standards

Because of these serious risks, both OSHA and JCAHO have implemented rules aimed at reducing the risk of injuries and reporting percutaneous injuries when they occur. The 2001 revised version of the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard from OSHA11 states that:

OSHA has determined that each employer having an employee(s) with occupational exposure to blood or other potentially infectious body fluids including semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, amniotic fluid, saliva in dental procedures, and any body fluid visibly contaminated with blood MUST establish a written Exposure Control Plan designed to eliminate or minimize employee exposure. OSHA further stipulates that the Exposure Control Plan shall be reviewed and updated at least annually and whenever necessary to reflect new or modified tasks and procedures that affect occupational exposure and to reflect new or revised employee positions with occupational exposure. And the facility must solicit input from nonmanagerial employees responsible for direct patient care on evaluation and selection of effective, safer engineering and work practice controls and document this solicitation.11

The revised OSHA standard also requires that healthcare facilities maintain a sharps injury log that must include the type and brand of device that caused the injury (if known), the department or work area where the injury occurred, and an explanation of how the injury occurred. Organizations that are found to be noncompliant with this requirement can face fines for failure to comply.

In July 2003, OSHA imposed $92,500 in penalties on a nursing and rehabilitation home and its parent company in Pennsylvania for violations of the bloodborne pathogens standard.12 Of this penalty, $22,500 was assessed for "serious" violations related to deficiencies in the exposure control plan, the safety device evaluation process (i.e., not including front-line healthcare workers in the evaluation and selection of safety devices), employee counseling following exposure, and handling of sharps containers. According to the OSHA citation, "The employer did not utilize engineering controls in the form of sharps with engineered sharps injury protections that isolated or removed bloodborne pathogen hazards from the workplace when injecting medications and utilizing catheters and other medical devices."12

OSHA determined that this facility had demonstrated the highest severity of occupational hazard, what it termed a "willful" violation. A willful violation is defined as "one committed with an intentional disregard of, or plain indifference to, the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Act." More detailed information on OSHA requirements and compliance issues is available on the OSHA Web site.

In addition to the many accreditation requirements surveyed by JCAHO, hospitals are also expected to be in compliance with the Environment of Care (EC) guidelines and the National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs), both of which include issues related to staff and patient safety and reducing the risk of injuries. Among many other issues, the Environment of Care addresses the need for hospitals and healthcare facilities to reduce and control environmental hazards and risks, prevent accidents and injuries, and maintain safe conditions for patients, staff, and other visitors. Staff must be aware of proper procedures for reporting injuries to employees or patients (EC 2.1), what actions to take following a blood or bodily fluid exposure (EC 2.3, 2.8), and which safety devices are available to reduce the risks of needle or sharps exposures (EC 2.3, 2.8).13

The JCAHO's NPSGs relevant to medication safety and proper labeling apply to all medications, including contrast media. All materials (both on and off a sterile field) must be labeled whenever they are transferred from the original packaging to another container. This applies to both hand-injected contrast as well as contrast administered via a power injector.14 Compliance with all the NPSGs is evaluated during JCAHO surveys. As of the February 2006 guidelines:

All NPSG requirements are scored as "Compliant" or "Not compliant." In that sense, they are treated as "A"-type Elements of Performance.... If one or more requirements under an NPSG are scored "Not compliant," the organization will receive a Requirement for Improvement for that Goal.14

In addition, JCAHO surveyors are required to ask healthcare organization leaders if they are familiar with the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act, and if these requirements are considered in the review of safer devices as well as in the decision-making process regarding replacement devices.

At St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, hospital-wide quality assurance protocols for blood and/or body fluid exposure have been implemented (Table 2, below) that follow the OSHA and JCAHO guidelines directly. Immediately following a sharps-related injury, the wound is to be cleaned and the employee is to obtain medical attention at either the employee health service or the emergency department. Written notification of the incident must be given to the manager within 24 hours, and employees must comply with employee health follow-up requirements.

Table 2: Quality assurance protocols for sharps injuries and blood/body fluid exposure at St. Joseph's Hospital Medical Center

- Clean the wound/area.

- Go to the Employee Health Service (EHS) immediately (or the emergency department if after hours).

- Written notification must be given to area manager within 24 hours.

- The employee must comply with EHS follow-up requirements.

- EHS to maintain the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sharps injury log.

Cost issues related to contrast packaging

In addition to the safety issues, the choice of contrast packaging can also have an economic impact on a healthcare facility, particularly with regard to waste disposal, product waste, and patient throughput.

Waste disposal

Waste disposal costs in radiology are often overlooked because they typically fall outside the department budget. These costs are significant, however, and should be viewed with a critical eye for facility-wide potential cost savings. In fact, the packaging of contrast material can have a dramatic impact on waste disposal costs.

According to OSHA guidelines, any glass bottle, including intact bottles, must be considered a sharp or hazardous material. Therefore, they must be disposed of in a puncture-proof container, not just as red bag disposal. They may certainly not be removed as regular waste.

Polymer containers, however, can be disposed of in the regular disposal. Community Memorial Hospital in Menomonee Falls, WI, recently renegotiated its waste disposal contract with a sister hospital. Since Community Memorial lowered the volume of sharps and hazardous waste, the hospital was able to reduce the price per pound for sharp or hazardous materials from 30¢ to 23¢. It is important to note, however, that even at 23¢, this cost is still approximately 10 times more expensive than regular trash disposal.

Glass bottles also create substantial waste disposal costs since they are heavier when they are disposed than other containers. An empty polymer contrast bottle is approximately 80% lighter than a comparably sized empty glass bottle, therefore offering substantial savings in waste disposal costs.

Contrast waste

A second financial consideration with contrast packaging is the cost associated with waste of the contrast media. With glass bottles, the contents of each bottle must be used immediately upon opening. Therefore, radiology departments and catheterization labs often stock various bottle sizes, and any contrast material left unused at the end of a single procedure is thrown out.

With multiuse "pharmacy bulk packaging" polymer bottles, healthcare facilities can stock larger-size bottles and can draw from a single container repeatedly, for up to eight hours, the amount that is needed per procedure. This thereby reduces wasted contrast in individual unit-dose-style bottles.

This type of storage and dispensing of contrast is especially efficient when imaging pediatric patients who require very small amounts of contrast. For example, rather than opening a 100-cc bottle for a 25-kg pediatric patient who only needs 50 cc of contrast for a study, the technologist can draw the exact amount needed from a multiuse 500-cc bottle.

Polymer packaging can also be cost-effective for procedures that require contrast for oral use. There are 50-cc polymer bottles of contrast for oral use that are ideal for mixing the volume of contrast directly with 36 ounces of suspension material -- either water, or, if the patient can tolerate it, a sugar-free drink mix. With the drink mix, however, it is important to remember that the dye could cause an allergic reaction. Therefore, all patients must be questioned carefully before contrast administration. Mixing the individual doses of contrast for oral use with the smaller containers of contrast helps eliminate the cost of unused contrast for oral use that often results when facilities mix one or more large vats of contrast for oral use each day.

Patient throughput

When a glass bottle breaks in a healthcare facility, the imaging employee cannot just pick up the broken glass pieces, even with a gloved hand. Typically, the environmental service team must be notified. Once they arrive in the department, they remove the glass shards using forceps or a broom and dustpan. When this happens in an imaging suite, the room may be closed for five to 20 minutes during the day. During off-hours, when the environmental services team may not be immediately available, the cleanup can take even longer.

This delay in room availability can have a significant impact on patient throughput, especially for a department with only one computed tomography (CT) system. For studies ordered using stroke protocols, in which the CT must be performed within 30 minutes, such a delay can also have adverse consequence for the patient.

The larger, multiuse polymer bottles can also improve technologist productivity. One pharmacy bulk pack can be used repeatedly for up to eight hours, eliminating the need to continually replace single-use containers. In addition, a programmable injector can draw up the contrast, which leaves the technologist free to prepare the patient.

The risk of bottle breaks

Although they are hard to quantify exactly (particularly because of underreporting), bottle breaks occur relatively infrequently. At Community Memorial Hospital, for example, as many as three or four glass breaks in a single day have occurred, and then there have been times when weeks passed between bottle breaks.

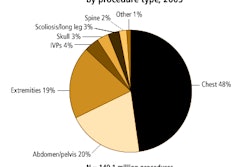

A 2003 Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet) study found that the vast majority of sharps injuries are caused by needles or scalpels, and that only 0.3% of reported injuries are caused by glass items and 2.6% are caused by other sharps items, including metal pull rings on glass bottles.15

Despite the relative infrequence of sharps-related injuries due to broken glass bottles, it is important to remember that any cut poses significant financial and health risks. However, if imaging departments and cardiac catheterization labs eliminate glass bottles, the risks of cuts are removed, thereby also preventing the direct and indirect costs associated with a worker injury. Simply put, if there is no cut, there is no cost.

Conclusion

Although polymer contrast media bottles are more expensive than comparable glass contrast bottles, their use can actually help to reduce overall costs through the department and healthcare facility. "Though most organizations believe they are doing what is necessary to prevent injuries, needlestick and sharps injuries continue to occur," according to Nancy Quick, CSP, CIH, OSHA compliance assistance specialist. "And, though cost is often cited as a factor for not using safer devices, it is actually a savings when you consider the cost of treating the individual once an injury occurs."16

Polymer packaging for contrast media eliminates the risks of sharps-related injuries from broken glass bottles and metal pull rings. The large, multiuse polymer packaging also increases patient throughput and reduces the amount of unused contrast that is often wasted with smaller, single-use glass packaging. Since empty polymer packaging is significantly lighter than glass and can be disposed of with the facility's regular waste (rather than in expensive puncture-proof hazardous waste containers), its use also offers substantial savings in waste removal. Thus, contrast media available in polymer packaging provides a safer alternative to today's traditional glass bottles, allowing adherence to guidelines on using safer engineering devices in healthcare today.

By Jill Blackburn, RT (R) (CT), and Rick Hawley, RT (R)(CT)

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

October 16, 2006

Ms. Blackburn is a CT technologist at St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix. She can be reached at [email protected]. Mr. Hawley is the lead CT technologist at Community Memorial Hospital in Menomonee Falls, WI. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Workbook for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Sharps Injury Prevention Program. CDC Web site. Available at www.cdc.gov/sharpssafety/wk_overview.html#overViewIntro. Accessed on June 17, 2006.

- Roy E, Robillard P. Underreporting of blood and body fluid exposures in health care settings: An alarming issue. Proceedings of the International Social Security Association Conference on Bloodborne Infections: Occupational Risks and Prevention. Paris, France, June 8-9, 1995:341. Abstract.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation of safety devices for preventing percutaneous injuries among health-care workers during phlebotomy procedures - Minneapolis-St. Paul, New York City, and San Francisco, 1993-1995. MMWR. 1997;46:21-25.

- Osborn EHS, Papadakis MA, Gerberding JL. Occupational exposures to body fluids among medical students: A seven-year longitudinal study. Ann Int Med. 1999;130:45-51.

- Abdel Malak S, Eagan J, Sepkowitz KA. Epidemiology and reporting of needle-stick injuries at a tertiary cancer center. Program and Abstracts of the 4th International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-Associated Infections; Atlanta, GA; March 5-9, 2000:123. Abstract P-S2-53.

- Tan L, Hawk C, Sterling ML. Preventing Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Settings: Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:929-936.

- California OSHA. Initial Statement of Reasons, California Code of Regulation. Title 8: General Industry Safety Orders Chapter 4, Subchapter 7, Article 109, Section 5193. Bloodborne Pathogens/Sharps Injury Prevention. June 24, 1999.

- Jagger J, Bentley M, Juillet E. Direct cost of follow-up for percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposures to at-risk body fluids: Data from two hospitals. Advanc Exposure Prevent. 1998;3(3):25-34.

- Pugliese G, Salahuddin M. Sharps Injury Prevention Program: A Step-by-Step Guide. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 1999.

- Perry J. Yale to pay $12.2 million in largest ever award in needlestick case. Advan Exposure Prevent. 1998;3(3):26.

- The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard from OSHA (2001) codified at 29 CFR §1910.1030[c][1][iv][b] and 29 CFR §1910.1030[c][1][v]).

- Perry J, Jagger J. Ground-breaking citations issued by OSHA for failure to use safety devices. Advan Exposure Prevent. 2003;6(6):61-64.

- 2006 Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 2006.

- National Patient Safety Goals. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Available online at: www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals. Accessed June 2006.

- Perry J, Parker G, Jagger J. EPINet Report: 2001 percutaneous injury rates. Advan Exposure Prevent. 2003;6(3): 32-36.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Preventing needlestick and sharps injuries. Sentinal Event Alert. Issue 22. August 1, 2001.

Related Reading

New contrast injectors go with the digital flow, September 28, 2006

OSHA citations loom as residents complain about sharps, February 3, 2004

Needlestick injuries: A "silent epidemic" in radiology, April 19, 2002

Education and awareness can prevent radiology workplace injuries, May 28, 2001

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com