As obesity becomes a national health issue in the U.S., a growing number of Americans are turning to surgery as a way to battle their bulge. But gastric bypass, one of the fastest-growing surgeries at U.S. hospitals today, poses multiple challenges for radiologists and technologists performing postprocedural imaging to detect complications.

An estimated 40,000 gastric bypass surgeries (GBP) were completed in 2001, according to the National Institutes of Health. Popularized by celebrities like NBC Today show weatherman Al Roker, interest in GBP has soared in recent years. Some facilities are conducting an estimated 500 gastric surgeries annually.

The procedure carries a 10%-20% risk of complication requiring follow-up surgery. Typical problems range from small bowel obstructions to major and minor leaks. An upper GI series (UGI) performed post-surgery detects most complications, followed by CT if necessary.

Recommended for morbidly obese patients with a BMI of 40 or more, the most common form of GBP combines capacity restriction and induced malabsorption. In recent years, the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) has emerged as the procedure of choice, with decreased recovery times and reduced complications compared to traditional surgery.

RYGBP involves creating a 15-30-ml gastric pouch that is anastomosed to a Roux limb brought up to the pouch and to the distal jejunum. The net effect is a decreased amount of food eaten and absorbed into the body, resulting in significant weight loss.

NBC’s Roker lost 100 pounds after undergoing a gastric bypass in March 2002. The average RYGBP patient generally loses two-thirds of their excess weight within two years after surgery.

As the number of procedures increases, so does the importance of familiarity with the signs of GBP complications and techniques for imaging larger patients, said Dr. Michael Federle, chief of abdominal imaging at the University of Pittsburgh.

"As straightforward as a leak or obstruction may seem, many radiologists are not going to make the diagnosis unless they look at the images very carefully," he said. "The anatomy is tremendously altered, and the findings are not necessarily evident, because image quality is often compromised."

Imaging’s role

Few researchers have focused on the role of imaging in RYGBP, but Federle and colleagues have documented multiple complications seen only on UGI or CT. The team’s findings have lead to changes in GBP surgical technique at the University of Pittsburgh (American Journal of Roentgenology, December 2002, Vol. 179:6, pp.1437-1442; Radiology, June 2002, Vol. 223:3, pp. 625-632).

"You can’t know if a patient has a leak without imaging," Federle said. "Even though many minor leaks heal spontaneously, more serious complications can arise if the leaks are not managed correctly."

The UGI series and CT play complementary roles in patient evaluation. The GI series is reliable in diagnosing leaks, and is routinely performed within 24 hours after surgery.

The study may be repeated later if a leak is not depicted but is suspected clinically. It can be difficult to recognize a small leak during the initial post-op GI series, only to diagnose it a few days later with a repeat study.

Typically, CT is the go-to technique to assess early complications such as leaks and obstructions at the anastomotic site between the Roux limb and gastric stump. In delayed complications occurring a month or more after surgery, CT is useful for diagnosing both the presence and cause of an obstruction, whether due to adhesion or hernia.

Both UGI and CT detect signs signaling adhesion or internal hernia, such as dilated bowel segments and a transition from dilated to collapsed bowel. But only CT depicts classic signs of internal hernia such as crowding, stretching, and engorgement of mesenteric vessels.

|

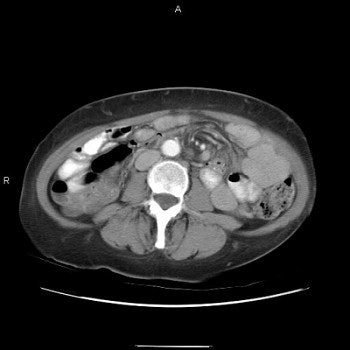

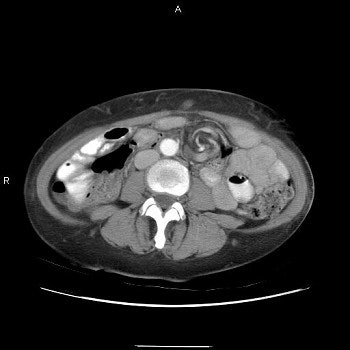

Three images show internal hernia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The CT scans (top, middle) and small bowel study (below) show a cluster of mildly dilated bowel segments in the left abdomen, with a crowded, twisted appearance of the bowel and mesenteric vessels. Images courtesy of Dr. Michael Federle.

|

In a retrospective review of 463 patients, in whom nearly 10% had complications seen on imaging, tracking patients with small bowel obstructions caused by internal hernia proved most rewarding. The work was presented at the 2002 RSNA meeting.

"The most unexpected byproduct of our work was finding internal hernia, which is almost unknown," Federle said. "We began looking at who had internal hernias and how the Roux limb had been constructed. As a result, our surgeons have actually changed the manner in which they do the surgery."

Tricky technique

The first challenge in detecting RYGBP complications is finding creative ways to image severely obese patients. Tipping the scales at 400 pounds or more, the extreme size of patients can strain the limits of imaging equipment, particularly fluoroscopic towers used for the commonly performed UGI.

For example, it can be difficult to penetrate patients with adequate contrast discrimination, and fluoroscopic monitoring of the procedure itself is sometimes not possible, Federle said.

"You have to modify the way imaging is performed," he said. "Most patients are too large to put on a table and then move the table. We usually have them stand on the floor in front of the x-ray table. It can be a squeeze sometimes to get them between the table and the fluoroscopic tower. Many patients barely make it."

Technologists need to be trained not only to position patients correctly, but quickly, he added.

"You have a 500-pound patient who is groggy after surgery and can barely stand, yet you are supposed to do an upper GI series on them," he said. "You’d better be able to do it in a couple of minutes or they are going to crumple to the floor."

At the University of California, San Francisco, which performs about 150 GBPs annually, patients who exceed x-ray table limits are given oral contrast and undergo a routine kidney-ureter-bladder exam (KUB) instead of the UGI.

"It’s not ideal, but there is not much you can do in that situation," said Dr. Fergus Coakley, chief of abdominal imaging at UCSF.

St. Michael’s Hospital in Stevens Point, WI, only recently discovered the weight limitations of its equipment when imaging larger patients, according to Kristin Glienke, supervising radiologic technologist.

"We now fluoro them one of two ways," Glienke wrote in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. "If patients can stand, we use our digital room, which has an intensifier that can be raised higher than our conventional room. If they can’t stand, there is only one table we can use (a 1991 Advantx with 105-mm capability, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). The intensifier can’t move as high, and we have to slide it very gingerly over the incision site."

CT scanning poses another set of problems. If patients exceed the table limit, there’s not much recourse, Coakley said. At UCSF, about 5% of GBP patients seen cannot be accommodated for CT. For others, several tricks can be employed to obtain usable images.

Dropping the tabletop to avoid the patient’s sides hitting the edge of the scanner helps avoid artifacts. Screening patients serially instead of spirally increases dose concentration and provides better images.

In addition, slowing down the time of rotation from one to two seconds is another technique that achieves the same goal, said Marco Patti, chief radiologic technologist at UCSF.

Additional tips, contributed by RTs around the country in response to a post on the AuntMinnie.com discussion board, include:

- Don’t try to lift patients. Nine times out of 10, they are capable of moving themselves.

- When performing CT scans on larger patients, save the belts on the table by not performing a scout view. If the radiologist is in agreement with the practice, it’s possible to image any patient who can fit in the gantry.

Part of the challenge in post-GBP imaging is that most imaging equipment has not been designed with large patients in mind, Coakley said. At St. Michael’s in Wisconsin, Glienke notes that the one table in the department that can accommodate large patients for UGI is due for replacement in the next two to three years.

"Even that table is not ideal," she said. "But I’m not sure what we’ll be able to replace it with one that can handle 600 pounds or more."

But the looming obesity crisis may make it imperative that imaging devices evolve accordingly. A new report by the London-based International Obesity TaskForce (IOTF) estimates that the number of overweight and obese people worldwide is as high as 1.7 billion. Professor Philip James, IOTF chairman, warned that the impact on health of the escalating obesity epidemic could overtake that of tobacco.

"It is clear that extreme forms of obesity are rising even faster than the overall epidemic, and we are witnessing a real health tragedy unfolding," he said (Reuters Health, March 17, 2003).

By Deborah R. DakinsAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

March 27, 2003

Additional reporting by Monica L. Lewis.

Related Reading

Brains of obese may be wired to enjoy food more, June 27, 2002

Few gender differences in brain's response to food, June 7, 2002

PET scans show just seeing food lights up the brain, May 24, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com

![Images show the pectoralis muscles of a healthy male individual who never smoked (age, 66 years; height, 178 cm; body mass index [BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], 28.4; number of cigarette pack-years, 0; forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], 97.6% predicted; FEV1: forced vital capacity [FVC] ratio, 0.71; pectoralis muscle area [PMA], 59.4 cm2; pectoralis muscle volume [PMV], 764 cm3) and a male individual with a smoking history and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) (age, 66 years; height, 178 cm; BMI, 27.5; number of cigarette pack-years, 43.2, FEV1, 48% predicted; FEV1:FVC, 0.56; PMA, 35 cm2; PMV, 480.8 cm3) from the Canadian Cohort Obstructive Lung Disease (i.e., CanCOLD) study. The CT image is shown in the axial plane. The PMV is automatically extracted using the developed deep learning model and overlayed onto the lungs for visual clarity.](https://img.auntminnie.com/mindful/smg/workspaces/default/uploads/2026/03/genkin.25LqljVF0y.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&crop=focalpoint&fit=crop&h=112&q=70&w=112)