AuntMinnie.com presents the final installment of a four-part white paper on pediatric imaging tips and techniques by Douglas Clark, R.T. (R) (CT).

Dose reduction is an area of pediatric CT that has gotten much press lately. Reports have demonstrated that CT dose can be reduced by 50% or more from the adult settings without detriment to image quality or image interpretation.

Along these lines, the American Journal of Roentgenology published weight-based guidelines for pediatric patients that I, and many CT techs I have spoken to in the U.S., have been utilizing (AJR, October 2000, Vol. 175:4, pp. 985-992).

|

Lbs. |

kg |

Chest (MA) |

Abdomen (MA) |

|

10-19 |

4.5-8.9 |

40 |

60 |

|

20-39 |

9-17.9 |

50 |

70 |

|

40-59 |

18-26.9 |

60 |

80 |

|

60-79 |

27-35.9 |

70 |

100 |

|

80-99 |

36-45 |

80 |

120 |

|

> 150 |

> 70 |

140 |

170 |

I emphasize that these are only guidelines for technologists.

You'll note that the above chart includes chest and abdomen techniques only. I had a technologist ask me once, in all seriousness, "What if the doctor requests a brain CT? How do I weigh the brain separately?"

Applications

Although they will vary from institution to institution, let’s cover some general applications and protocols for pediatric imaging.

First, let me state that for most facilities, ultrasound, not CT, is the modality of choice for newborns, infants, and some toddlers. CT is utilized for specific problems such as abscess, blunt-force trauma, and neoplasm, to name a few.

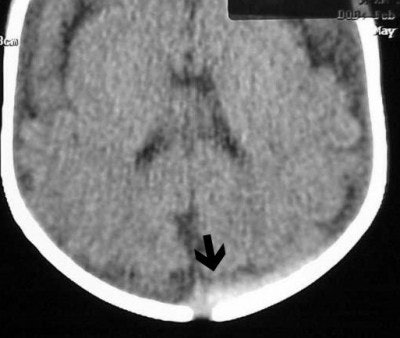

As for blunt-force trauma, say you have a child who is a suspected victim of child abuse (non-accidental trauma). Doctors are looking for an inter-cerebral bleed but nothing is obvious on the axial scan. Are there alternatives?

If the c-spine is cleared, then extend the child’s head as in a reverse coronal position (Figure CT 3). If the c-spine is not cleared, then you can affix the child to a backboard and tilt the foot of the board up about 30°-45° or so. Scans through the brain, if positive, will show blood collecting in the superior convexity (Figure CT 4), an almost definite sign of non-accidental trauma.

|

| Figure CT 3 |

|

| Figure CT 4 |

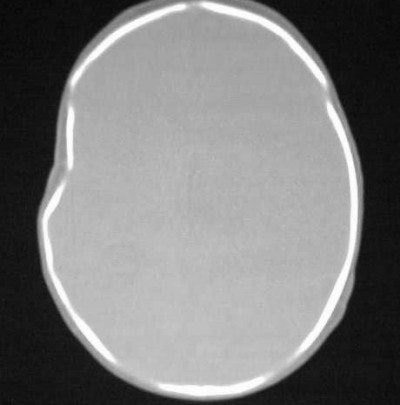

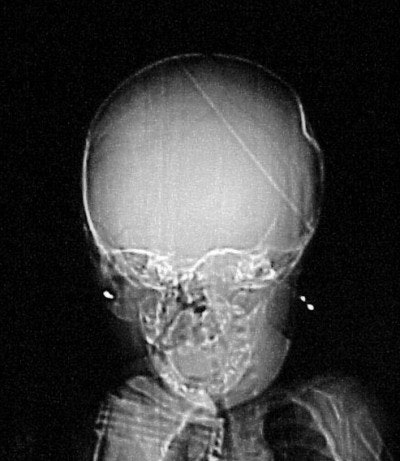

How about CT imaging for an in vitro trauma? Figure CT 5 is an axial image of a newborn child; there were no problems during the caesarian delivery. Two physicians and three nurses were present and the child was noted to have an indentation to the temporal region of the skull. Plain films were positive for a depressed skull fracture (Figure CT 6).

|

| Figure CT 5 |

|

| Figure CT 6 |

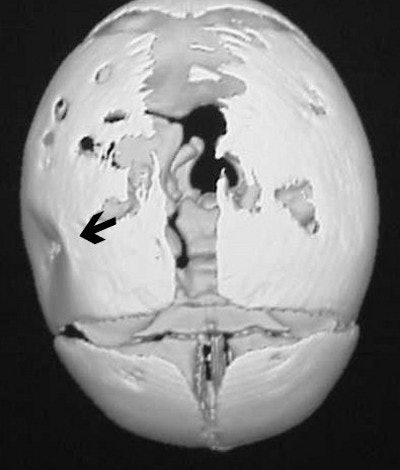

Three-dimensional reconstructed images in surface-shaded volume rendering show an obvious breech of the skull in the affected area (figures CT 7 and CT 8). Detectives matched the defect to a pair of the father’s cowboy boots. He was charged and convicted of beating his wife during the pregnancy.

|

| Figure CT 7 |

|

| Figure CT 8 |

Three of the most common neoplasms in children are neuroblastoma, Wilm's tumor of the kidney, and rhabdomyosarcoma. With increased scan time and the capability to do multiplanar reformations (MPR) showing vascular or spinal compromise/invasion, spiral CT is a definite advantage for making a timely, accurate diagnosis in the pediatric patient.

Case 1: The patient is a three-year-old black female who appears to be in no distress. The mother stated that she was giving the child a bath and noticed that her abdomen looked distended, and harder on the left side than the right. All the child’s labs are normal, and there is no family history of medical problems.

|

| Figure CT 9 |

In Figure CT 9, the scout film shows a gaseous abdomen with displacement of bowel contents towards the right lower quadrant.

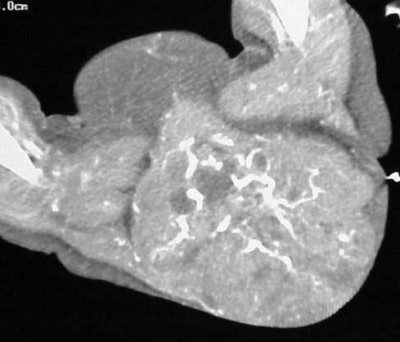

Axial images (Figures CT 10 and CT 11) show a mass beginning just below the kidneys on the left side and extending almost through the pelvis. The child was diagnosed with Wilm’s tumor of the left kidney.

|

| Figure CT 10 |

|

| Figure CT 11 |

She underwent a left nephrectomy and chemotherapy and recovered well.

Case 2: The patient is a newborn girl with a large soft-tissue mass extending from her buttocks through her thighs. The scout AP image (Figure CT 12) shows an extensive, rounded soft-tissue mass.

|

| Figure CT 12 |

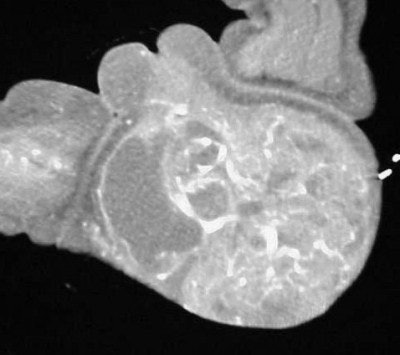

It is uncommon to use contrast in an infant less than six months old because their kidneys are not yet fully developed. In this case, doctors decided that the benefits were worth the risk of harm, so I used 4 cc of Visipaque (iodixanol, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) hand-injected through a 24-gauge angiocath with a 20-second delay.

|

| Figure CT 13 |

|

| Figure CT 14 |

Images (Figures CT 13 and CT 14) show a large, enhancing, soft-tissue mass extending from the buttocks, past the labial folds, and into the thighs. She was diagnosed with a rhabdomyosarcoma that was successfully excised.

General protocols for pediatric CT

Brain

- Collimation: 5 x 5 mm axial

- mAs: 80 (for neonates) -- 150

- kVp: 120

- We generally scan 5-mm conventional axial images in children up to 12 years of age, then go to an adult protocol.

Chest

- All scans done helical

- Collimation: 5 x 5 mm (0-7 years); 7 x 7 mm (7 years and older)

- Range: From apices through adrenals

- mAs: use weight-based chart

- IV contrast: 1-2 cc/kg

- Delay: 15-seconds post injection

Abdomen

- All scans done helical

- Collimation: 5 x 5 mm (0-7 years); 7 x 7 mm (7 years and older)

- Range: Diaphragm through symphysis pubis

- mAs: Weight-based chart

- IV contrast: 1-2 cc/kg

- Delay: 20-seconds post-injection

- Oral contrast: Based on age and radiologist protocol

Appendicitis

- All scans done helical

- Collimation: 7 x 7 mm from the diaphragm through area of appendix; 5 x 5 mm through pelvis. Oral contrast: 60 minutes prior to scanning or rectal contrast per radiologist order IV contrast: Per radiologist order.

Note that some radiologists use rectal contrast only, and some use a limited scan range of 5 x 5 mm from L1 through the symphysis pubis with rectal contrast only.

Teaching case twins

The patient is a 12-year-old twin girl, approximately 5 feet 2 inches, 100 lb, who is complaining of lower abdominal fullness. Mom noticed the daughter’s "little pouch" (Figure TC 1).

|

| Figure TC 1 |

Note both large and small bowel being pushed out of the way in the mid-abdomen region, leaving a large, circular appearance (arrow).

The mother did all the talking, and the patient would not make eye contact. The patient said that her abdomen was not painful, just uncomfortable. Neither she, nor her sister, had any prior medical history and no drug allergies.

Her first period was three months ago and she had not had one that month, but she stated that she was not sexually active. All lab work was within normal limits with the exception of the pregnancy test (B-hcg), which the referring physician did not order because it was "not within her differential diagnoses." Her doctor did order an ultrasound of the pelvis and a CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

Our radiologist attempted to encourage her doctor to get an HCG but she refused. So our radiologist had the ultrasound done first and the technologist found a normal uterus and ovaries with a large soft tissue mass in the abdomen.

On the basis of these findings, our radiologist approved a CT of the abdomen and pelvis with both oral and IV contrast.

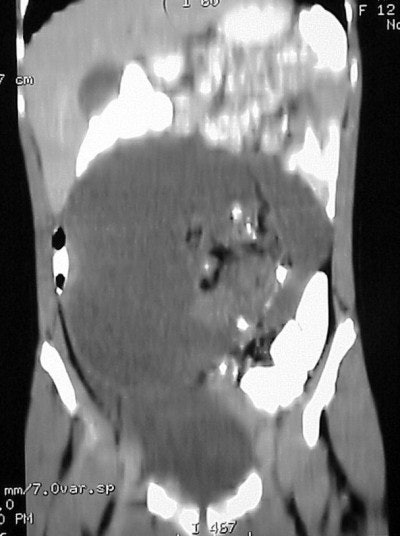

The child received 16 oz of oral contrast over a 1-½ hour period, and 75 cc of Visipaque was given at the time of scan. Contiguous helical images were obtained using 5-mm collimation at 5-mm intervals from the level of the diaphragm through the symphysis pubis. We used 150 mAs, 120 kVp, and a scan delay of 75 seconds.

|

| Figure TC 2 |

The image (Figure TC 2) demonstrates a contrast-filled bowel, the tip of the liver on the right, and a soft-tissue mass appearing at the level of the kidneys in the anterior portion of the abdomen.

|

| Figure TC 3 |

|

| Figure TC 4 |

In figure TC 3 we can see a large soft-tissue mass measuring approximately 9 cm wide by 6 cm in AP diameter, and 14 cm in height. It contains both fluid and semi-solid components of soft tissue as well as assorted calcifications. The mass appears to terminate (Figure TC 4) just above the level of the uterus (arrow).

|

| Figure TC 5 |

|

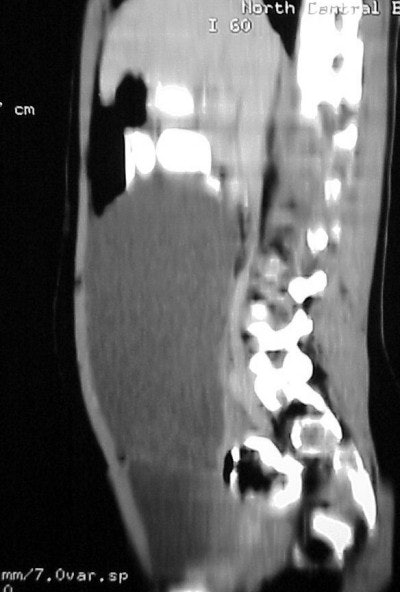

| Figure TC 6 |

The images (Figures TC 5 and TC 6) show, respectively, a sagittal and coronal MPR of the axial images, demonstrating the size and volume of the structure.

What is in the differential diagnoses for this child? What is the mass and how did it grow?

The preliminary diagnosis was confirmed at surgery as a benign teratoma, or a dermoid cyst.

A dermoid is a sac-like growth, present at birth, which contains hair, fluid, teeth, or skin glands. They usually occur on the ovaries, and in rare instances, on the face, skull, and lower back. The structures become trapped during fetal development and grow slowly.

In a way, this 12-year-old girl was pregnant -- with her own sister. The twins were originally conceived as triplets and for whatever reason, when the egg divided it was retained by one of the siblings rather that being discharged by the mother. It attached to her uterus and began to develop with the onset of her menstrual cycle and the hormonal influx.

I hope you'll be able to use some of these pediatric imaging insights in your daily practice. No matter how long we’ve been imaging patients, none of us has all the answers. It’s all a learning process, and the key is to stay open to that process. Remember that those we learn from need not be older or standing in the front of a classroom.

By Douglas ClarkAuntMinnnie.com contributing writer

May 12, 2004

Clark is a staff CT technologist with University Health System in San Antonio, TX, and has been a radiographic technologist since 1990.

Bibliography

Ruiz Mario MD, Weirsig Jeremy MD, "Protocols for Pediatric Body CT," North Central Baptist Hospital, San Antonio, Texas 2000

Huang Ben DO, "Dermoid Cyst Removal," www.Emedicine.com, 10 April 2003

Related Reading

Part III: Imaging the pediatric patient: the use of CT in pediatric imaging, May 7, 2004

Part II: Imaging the pediatric patient: diagnostic radiography, April 26, 2004

Part I: Imaging the pediatric patient: beyond the smiles and stickers, April 22, 2004

Misread scans often lead to osteoporosis diagnosis in children, March 22, 2004

PET/CT brings added value to pediatric oncology, February 27, 2004

Copyright © 2004 Douglas Clark