A glance at the newspaper or TV is all it takes to learn about health problems associated with painkillers, particularly those based on COX-2 inhibitors. First came the arthritis drug Vioxx (Merck and Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ), which was yanked from the market in September following a report that nearly 28,000 patients may have suffered heart attacks or sudden cardiac deaths resulting from its use.

Then Pfizer's Celebrex, the most widely recommended Vioxx replacement prescription, hit the skids in December when a study showed that it, too, heightened heart-attack risk, at least in higher-dose regimens. Bextra, a second COX-2 inhibitor-based drug by New York City-based Pfizer, was recently found to increase the incidence of heart problems and blood clotting after cardiac surgery. Last week a National Institutes of Health study linked naproxen to an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.

And on Monday, bowing to charges that it had actively suppressed the publication of negative data on the safety of Vioxx, the FDA said it would permit Senate whistleblower Dr. David Graham to publish his Vioxx study -- presumably in The Lancet, according to the Associated Press. Vioxx was responsible for as many as 139,000 heart attacks, a third or more of them fatal, the study concludes.

The dust hasn't settled yet on the great autumn drug debacle, not by far. But in a few short weeks this series of unfortunate events has set mighty drug companies reeling, put the FDA on the defensive, and brought sweet vindication to critics disturbed by what they see as excessive coziness between drug companies and U.S. regulators.

Meanwhile, patients scrambling for pain-management alternatives are finding there's no free ride on the safety train, even when they confine themselves to over-the-counter analgesics. Too much acetaminophen (Tylenol) can cause liver tissue necrosis and kidney toxicity. Ibuprofin (Motrin, Advil) can increase vascular porosity, with potential cardiovascular implications of its own.

And as investigators at the 2004 RSNA meeting in Chicago noted, analgesic overuse can lead to analgesic nephropathy and end-stage renal disease. As many as 5% of new cases of chronic kidney failure each year may be caused by chronic overuse of analgesics, researchers have estimated.

But the incidence in the U.S. may in fact be significantly lower, and noncontrast CT may be a poor method of detecting analgesic nephropathy, according to the RSNA presentation in December.

"Heavy analgesic use has been implicated in the etiology of a unique nephropathy characterized by renal hydronephrosis, chronic interstitial nephritis, and other forms of chronic renal disease," said Lauren Brubaker from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill. "However, prior studies were unable to delineate the precise relationship between analgesic intake and chronic renal insufficiency, which is poorly understood still."

Thus the three-year National Analgesic Nephropathy Study (NANS) was undertaken to address hypotheses related to analgesic use, she said. Five medical institutions throughout the U.S. participated in the study. Data analysis was performed at the Boston University School of Public Health.

The investigators hoped to define a characteristic renal pathologic entity associated with analgesic overuse, and determine if such a syndrome could be reliably detected on noncontrast CT, as recent European studies have suggested. They used their results to examine the incidence and prevalence of analgesic nephropathy among end-stage renal-disease (ESRD) patients in the U.S.

The study included 221 patients with ESRD, who were examined with noncontrast CT. Excluded were patients with diabetes, polycistic renal diesase, renal artery stenosis, acute renal failure, sickle-cell disease, and other nonanalgesic ESRD etiologies. Drug histories were provided for all patients.

The patients were imaged using a nonenhanced spiral CT technique at 5-mm collimation, pitch one, and a single breath-hold. The images were assessed for kidney volume, parenchymal thickness, contour, and calcifications.

Volume was measured twice, first with an ellipse technique that calculated volume based on length, width, and AP diameter of each kidney x 0.959. Then the team applied the a voxel-measuring technique as a reference standard -- by manually outlining the renal parenchyma in each image slice, and summing it all up on the computer to get total volume. Finally, anterior, posterior, and lateral thicknesses were measured for each kidney, Brubaker said.

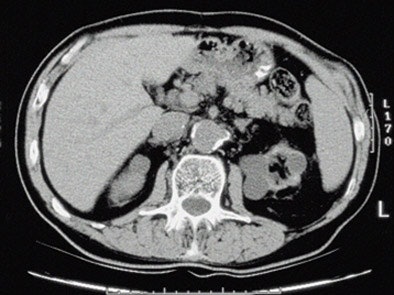

|

|

|

| Top to bottom: Indented kidneys with cysts typical of ESRD, but not 'SICK,' seen in a 61-year-old patient. All patients were imaged within three months of ESRD diagnosis and the beginning of dialysis, and yielded only subtle CT findings in most of them. All images courtesy of Lauren Brubaker. |

"We developed the acronym 'SICK' to indicate bilaterally small, indented, and calcified kidneys," she said. "In terms of radiological findings, as you would expect, we found small, smooth kidneys in 65% of our ESRD population. Other typical ESRD patterns were small kidneys with cysts, as well as kidneys with so many cysts they are causing indentations or scars within the kidneys. Contour was assessed for calcification through scars, as well as calcifications for size and location."

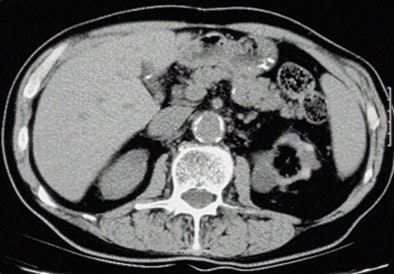

|

| Above: Small kidneys with cysts. Below: Typical ESRD pattern of small, smooth kidneys. Typical symtoms include edema, low urine output, confusion, weakness, flank pain, or nausea and vomiting. |

The results showed that "only 15/221 (7%) of the patients in the ESRD population met the SICK criteria, corresponding to 7% of our ESRD population," Brubaker said, adding that heavy analgesic use (at least 0.3 kg per year for a year or longer) at least nine years before symptom onset occurred in only 5/15 (33%) of patients with SICK, compared to 7% of those without SICK (RR = 11, p < 0.01). And even then, 3/5 patients who had both SICK and high analgesic use had taken phenacetin, a drug that is no longer in use in the U.S.

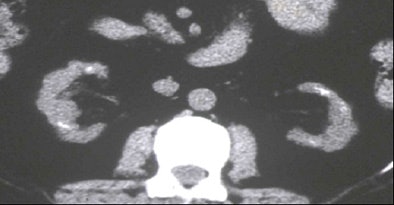

|

| One of the few patients who clearly met the SICK (small, indented, and calcified kidneys) criteria was a 72-year-old male with progressive analgesic nephropathy. Image above shows increased parenchymal thickness, coarse papillary calcifications bilaterally, and numerous indentations. |

Overall, CT scan detected just 5/19 heavy analgesic users, for a sensitivity of just 26%, though there were no false-positives, Brubaker said. Excluding phenacetin users left just 2/16 heavy analgesic users detected using noncontrast CT, a sensitivity of just 13%. Overall, 191/221 patients had negative CT exams; specificity was 95%.

"We do believe that there is an association between SICK and heavy analgesic use," Brubaker concluded. "But it's largely dependent on phenacetin, so it's not of much interest at the moment. Our main conclusion is that the noncontrast CT scan is not a sensitive diagnostic tool for analgesic nephropathy in the U.S., because the majority of heavy analgesic users do not meet the CT criteria for SICK. And last, we think that SICK is rare in the U.S., occurring in only about 1% of our ESRD population."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 5, 2005

Related Reading

Renal mass with nonrenal malignancy may not need biopsy, December 2, 2004

US, MRI challenge CT for classifying renal cell carcinoma, June 17, 2003

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com