Today's volumetric MDCT images are yielding a troubling trove of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. The vast majority of such lesions smaller than 3 cm are benign, but it takes a bit of sleuthing to rule out malignancy based on imaging alone.

In most cases a combination of CT features, clinical clues, and follow-up can eliminate a differential diagnosis of carcinoma, according to Dr. Brooke Jeffrey, professor of radiology and chief of abdominal imaging at Stanford University in Stanford, CA.

"With MDCT you will see these small cystic lesions with disturbing frequency, and the question becomes what do we do about them; what is their potential for malignancy and how should we manage them," he said in May at the International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT held in Las Vegas.

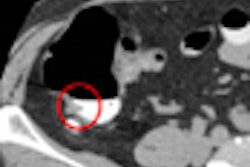

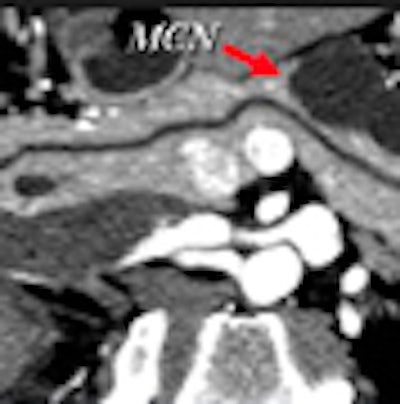

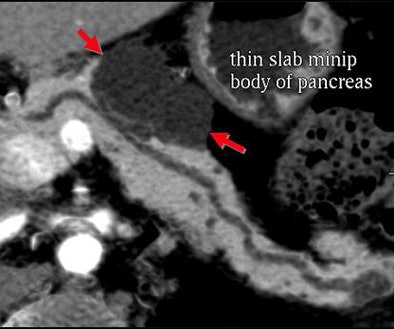

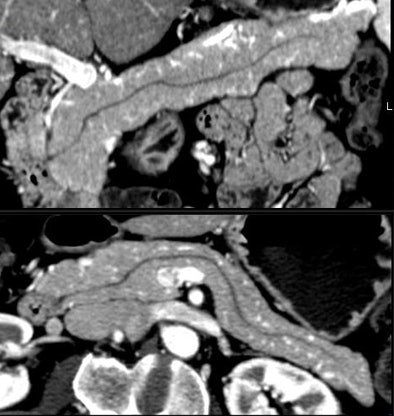

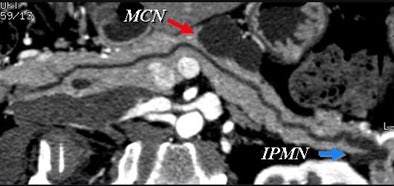

Certainly imaging-based diagnosis of the cysts has its limitations. For one thing, MDCT can diagnose six different pancreatic lesion types, including side branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), serous microcystic adenomas, epithelial cysts, mucinous cystic neoplasms, lymphatic cysts, and cystic islet cell tumors. But it can't always tell them apart.

Some lesion types look the same at CT, with overlapping appearance occurring, for example, between a mucinous cystic neoplasm and a thin-walled simple cyst that has no risk of malignancy. And mucinous cystic neoplasms are indistinguishable from benign epithelial cysts.

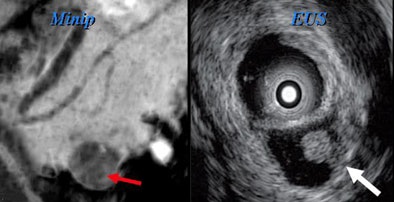

"There's no way to distinguish them, so by the time your cyst has exceeded 4 cm, you've pretty much bought yourself a needle aspiration," Jeffrey said. Esophageal EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration is the key to differentiating these small cyst types and in fact the way to evaluate most lesions larger than 3 cm in diameter.

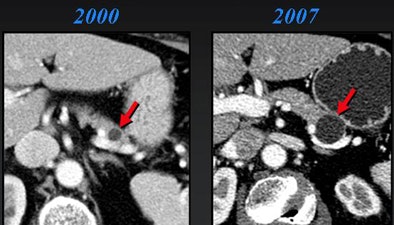

Worrisome features for malignancy are solid tissue within the cyst, obstruction of the main pancreatic duct ≥ 1 cm or the common bile duct, regional lymphadenopathy, or interval enlargement of a lesion, Jeffrey said.

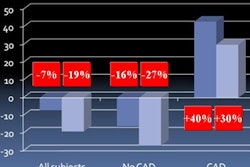

More than one study has shown that incidental pancreatic cysts are as much a phenomenon of aging as of improved imaging. In a series of 212 patients who had surgery for pancreatic cysts over five years, for example, Fernandez del Castillo and colleagues found that incidental lesions were more common in asymptomatic older patients compared to a younger symptomatic group (65 ± 13 versus 56 ± 15 years, p < 0.001). And only one (3.5%) of 28 asymptomatic cysts smaller than 2 cm had cancer compared with 13 (26%) of 50 cysts larger than 2 cm (p = 0.04), the authors wrote (Archives of Surgery, April 2003, 138:4, pp. 427-434).

Earlier this year, a study from the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor noted an association between age and malignancy in 160 pancreatic surgery patients. The mean age of patients with malignant pancreatic cysts was 67 years, versus 62 years for patients with benign disease (p < 0.05).

Gender also mattered, with male patients having a higher incidence of malignancy (19/67, 28%) compared to female patients (12/99, 12%; p < 0.02). Significantly, more than 90% of patients with malignancy had at least one symptom, including jaundice (p < 0.001), weight loss (p < 0.003), and anorexia (p < 0.05), Lee and colleagues wrote (Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, February 2008, Vol. 12:2, pp. 234-242).

"So it's reassuring if your patient is asymptomatic -- the lesion is most likely benign," Jeffrey said.

In their series, Lee et al also reported the radiographic features correlating to malignancy as presence of a solid component (p < 0.0001), main pancreatic duct dilation (p = 0.002), common bile duct dilation (p < 0.001), and lymphadenopathy (p < 0.002).

"The presence of solid tissue within cystic lesions in addition to regional lymphadenopathy and interval enlargement are all very significant features suggesting malignancy," Jeffrey said.

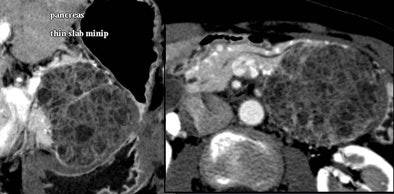

Small cystic lesions not worrisome for malignancy under 3 cm include side branch IPMNs, and serous microcystic adenomas, which are easily characterized by their honeycomb matrix that is also easily seen on ultrasound, Jeffrey said.

Serous cystic tumors are by far the most common pancreatic cystic lesions, Jeffrey said. They are nearly always microcystic, with macrocystic serous lesions occurring in about 4% of cases. They also are benign and can be managed with follow-up but not surgery, he said.

In Jeffrey's Stanford radiology group, Kilpatrick et al recently followed 156 patients with cysts smaller than 3 cm and no worrisome features at CT over three years. In all, 86 had follow-up of more than two years (n=28), one to two years (n=13), six to 12 months (n=22), and less than six months (n=23).

Nineteen of the 156 patients had surgery, while only three cases were malignant, Jeffrey said. Most important, all malignancies had solid tissue within the lesion at CT. Interval growth was also a predictor. Lesions grew in seven cases, including two of the three malignancies, Jeffrey said of the study (Abdominal Imaging, January-February 2007, Vol. 32:1, pp. 119-125).

"The take-home message here is that those that have solid internal tissue or enlarge over time have potential for malignancy," he said. "Interval growth was seen in seven cases, two of which were malignant, so obviously benign lesions can also grow over time."

It's also worth noting that small cystic lesions are quite common, especially with advancing age. And the vast majority, including side branch IPMNs, microcytic adenomas, and epithelial cysts, are benign, Jeffrey said.

"If they're greater than 3 cm, we're going to want to go on to needle aspiration, but when they're small -- and particularly if we can identify distinctive morphological features -- we can be very comfortable following these with imaging [MDCT, EUS, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)]," he said. "Cystic cancers are rare, but they invariably have solid components or increase [in size] over time."

There are no data on the optimal follow-up time or imaging method (CT, EUS, or MRCP). However, several authorities have suggested a one-year follow-up interval for lesions smaller than 1 cm and a six-month follow-up for larger lesions, with follow-up directed at assessing size and the presence of internal solid tissue within the cyst, he said.

Researchers have also experimented with ethanol ablation under EUS guidance for cysts 1 cm and smaller, Jeffrey said of a pilot study from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Gan et al found that in eight of 23 (35%) patients with complete follow-up, the cysts resolved completely, with evidence of epithelial ablation in five other patients who underwent surgical resection (Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, May 2005, Vol. 61:6, pp. 746-752).

"There were no serious complications," Jeffrey said. "This potentially may be the best way to go with these patients rather than serial follow-up."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

June 9, 2008

Related Reading

Survival benefit seen with radiation therapy in early pancreatic cancer, February 6, 2008

CTA of the pancreas reduces failed resections, December 25, 2007

MDCT's 'virtual Whipple' offers practice run before complex surgery, August 16, 2007

High contrast flow rate best for pancreas CT, November 8, 2006

CT features diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis, February 2, 2006

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com