CT screening for lung cancer may provide a moderate reduction in lung cancer mortality among smokers, according to a study in the July issue of Radiology. The reduction in deaths from all causes due to screening was modest, however, due to competing causes of death among smokers of increasing age.

Lung cancer is responsible for more deaths each year than breast, prostate, and colon cancers combined, noted study authors Pamela McMahon, Ph.D., from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, where the patients were screened with CT. A model based on the screening program and six-year follow-up was used to predict the effect of lung cancer screening on mortality.

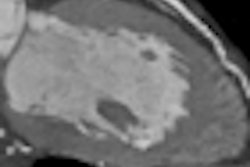

Although mean survival is fewer than five years for patients whose lung cancers are left untreated, surgery can improve the prognosis markedly, the authors wrote. One study found that more than 80% of patients whose lung cancers were resected were still alive 10 years later.

Nevertheless, the benefit of lung screening with CT remains undetermined, with some studies finding a marked benefit to screening while others have found none. In the present study, researchers used a screening study of 1,520 current or former smokers to populate a microsimulation model of lung cancer development, treatment results, and outcomes.

The model predicted diagnosed cases of lung cancer and deaths per simulated study arm, which consisted of five annual screening examinations versus no screening. The main outcome measures were predicted changes in lung cancer-specific and all-cause deaths as functions of follow-up time after simulated enrollment and randomization, the authors wrote.

LCPM model

The researchers used screening data from 1,520 current or former smokers (ages 50-85, mean age 59, 61% current smokers) to populate the Lung Cancer Policy Model (LCPM), "a comprehensive microsimulation model of lung cancer development, screening findings, treatment results, and long-term outcomes," the authors wrote (Radiology, July 2008, Vol. 248:1, pp. 278-287).

"The LCPM is a state-transition model analyzed as a patient-level Monte Carlo simulation to allow for individual heterogeneity in risk factors (e.g., smoking history) and event rates," the authors explained. Because LCPM models survival after screening detection as a function of disease characteristics, it avoids the "problematic assumption inherent in stage-shift models," namely, that screening-detected cancers behave like nonscreening-detected cancers, they wrote.

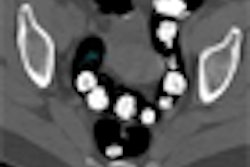

The LCPM explicitly models benign nodules, thereby addressing the gap between cancer prevalence of 1% to 2.7% and the 23% to 51% prevalence of nodules in screened smokers. It also incorporates the competing mortality risks faced by cigarette smokers, a necessary step to avoid inflated estimates of the effect of screening on mortality, the authors noted.

The LCPM's "natural history parameters were estimated by populating the LCPM with individuals assigned a smoking history that was representative of a specified age-sex-race-calendar year cohort of the U.S. population, and by calibrating the model to tumor registry data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute," they wrote. Data from published clinical studies were used as secondary calibration targets.

Modest reduction due to screening

"The percentage of prevalent cancers that were adenocarcinoma (observed, 71%; predicted, 71.4%), the percentage of prevalent [non-small cell lung cancers, NSCLCs] that were stage I (observed, 68%; predicted, 72.6%), and the median diameters of prevalent cancers (observed, 13 mm; predicted, 10 mm) were similar for the model and the study; standard deviations of both observed (13 mm) and predicted (8.5 mm) diameters were large," the group reported. "Among patients with a diagnosis of prevalent lung cancer, the LCPM predicted smoking histories that were consistent with the smoking histories of the participants in the study."

Based on five years of annual screening exams in patients with detected nodules, the modeled six-year follow-up arm had an estimated 37% relative increase in lung cancer detection compared to the control arm, the authors reported. At 15 years' follow-up, five annual screening examinations yielded a 9% relative increase in lung cancer detection.

The relative reduction in cumulative deaths from lung cancer from five annual screening examinations was 28% at the six-year follow-up and 15% at the 15-year follow-up. The relative reduction in cumulative all-cause mortality from five annual screening examinations was 4% at the six-year follow-up, falling to 2% at 15 years.

"One of the 11 hypothetical individuals who would have died from lung cancer in the absence of screening died of other causes within the same 15 years after enrollment," the authors noted. Iatrogenic deaths were rare but were 37% more likely in the screening arm, at 30 deaths per 100,000 individuals, compared with 22 deaths per 100,000 in the control arm. A stage shift was predicted in the screening arm versus the control arm, they noted.

Compared with NSCLCs diagnosed in the control arm, NSCLCs diagnosed in the screening arm were 3.6 times more likely to be stage I (68% versus 19%) and 6.5 times less likely to be stage IV (8% versus 52%), they wrote. The absolute number of stage IV cancers was lower in the screening arm than in the control arm.

For its part, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents a significant portion (15%) of cases in the study, "but because of its short doubling times and aggressive disease progression, the benefit from detecting SCLC with screening is generally believed to be minimal," the authors wrote. "We predicted no difference in detection of SCLC in the two trial arms."

Statistical modeling offers a way to use available data to inform current screening decisions while awaiting long-term mortality data, they noted. "Our results suggest that adding a control arm to the Mayo CT study would have provided some, but not significant (p > 0.05), evidence of a moderate reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality caused by screening," they wrote.

This finding lies between the conclusions of two recent high-profile studies, "one of which [International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP), Henschke et al] concluded that screening offered a large benefit, and the other of which [Bach et al] concluded that it offered no benefit," they wrote.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 22, 2008

Related Reading

Smoking during radiation therapy reduces treatment benefit, July 16, 2008

Diligence can reduce missed lung cancers in CT, June 23, 2008

Benefit small from lung cancer screening method, June 11, 2008

Ground-glass nodule features on CT reveal malignancy risk, April 29, 2008

Evidence for lung cancer screening deemed overstated, December 4, 2007

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com