A landmark study that tracked pediatric CT radiation doses in large health maintenance organizations (HMOs) across the U.S. found that the volume of CT scans nearly doubled between 1996 and 2005, and that the scans may put young patients at greater risk of future cancer, according to JAMA Pediatrics.

The projected lifetime risks of cancer were highest for younger patients and girls and lowest for older patients and boys, concluded the authors of the 15-year retrospective study, which measured hundreds of individual radiation doses. Cancer risks were also higher for patients undergoing scans of the abdomen/pelvis or spine, compared with other areas. Head scans of children younger than 5 years produced the highest risks of leukemia.

In all, the authors projected that the 4 million pediatric CT scans of the head, abdomen/pelvis, chest, or spine performed each year will cause 4,870 future cancers in the U.S. However, they also found that simply eliminating the highest-dose exposures -- some of which were more than 20 mSv for reasons that could not be easily explained -- could reduce the toll by almost half (JAMA Pediatr, June 10, 2013).

"We found a pretty dramatic increase in CT use over 10 years ... and we found wide variability in the dose for the same type of study, and so that variability, combined with the increased use, leads to some children receiving relatively high doses for medical imaging," lead author Diana Miglioretti, PhD, told AuntMinnie.com. Miglioretti is a senior investigator at the Seattle-based Group Health Research Institute and a professor of biostatistics at the University of California, Davis.

An accompanying editorial by Dr. Alan Schroeder and Dr. Rita Redberg, also published on June 10, said that society needs to come to terms with the idea of more watching and waiting and less scanning.

Price of progress?

CT has greatly improved diagnostic capabilities in the past two decades, but its use has come with risks, wrote Miglioretti and colleagues including Eric Johnson; Andrew Williams, PhD; Robert Greenlee, PhD; and Dr. Rebecca Smith-Bindman. CT doses are 100 to 500 times those of conventional radiography and are in ranges that have been linked to the development of cancer in children, who are both more sensitive to the effects of ionizing radiation and have many years of life remaining for cancer to develop.

The study evaluated the use of CT in children younger than 15 between 1996 and 2010 at six large healthcare centers: Group Health Cooperative in Washington; Marshfield Clinics in Wisconsin; and Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, and Northwest. The study included more than 4.8 million child-years of observation, according to the researchers, who calculated doses from DICOM data for 744 CT scans performed between 2001 and 2011.

The group examined radiation exposure from CT scans, calculating dose at the individual level, Miglioretti said. The researchers also sampled hundreds of exams of each CT type, extracted dose parameters, and used modeling developed at the U.S. National Cancer Institute to estimate organ dose for each individual child based on the parameters for his or her individual exam.

From there, they estimated lifetime attributable risks of cancers from the observed organ doses using age- and sex-specific cancer risk models in the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR) VII report for breast, colon, liver, lung, ovarian, prostate, stomach, thyroid, bladder, and uterus cancers, as well as leukemia. A study by Berrington de Gonzalez et al was used to estimate the risk for oral, esophageal, rectal, pancreatic, kidney, and brain cancers. All told, these cancers account for 70% to 85% of U.S. cases, they said. The linear no-threshold dose-response model was used to estimate solid-organ cancer risk, and leukemia risk was estimated from red bone marrow doses.

Analyses were performed for 150,000 to 370,000 children for each year of the study. Girls made up half of the population, and 29% were younger than 5 years of age. CT use increased between 1996 and 2005, remained stable between 2005 and 2007, and began to decline thereafter.

More scans, higher doses

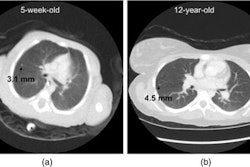

The researchers also examined CT use among specific subpopulations. Among children younger than 5 years, for example, CT use doubled from 11 scans per 1,000 children in 1996 to 20 scans per 1,000 children between 2005 and 2007. It then decreased to 15.8 scans per 1,000 children in 2010.

The head was the most commonly scanned region, with CT use increasing by approximately 50% from 1996 to 2010. From 1996 to 2010, the number of chest scans also increased by 50%, while the number of spine scans increased between four- and ninefold.

The largest effective doses were found in abdomen/pelvis scans, with the mean dose increasing from 10.6 mSv among children younger than 5 to 14.8 mSv among children 10 to 14 years old. Effective doses of 20 mSv or higher were delivered in 14% to 25% of abdomen/pelvis scans, 3% to 8% of chest scans, and 6% to 14% of spine scans for children depending on whether they were younger or older than 5.

Many of the doses were high for reasons the authors couldn't glean from the data. In head scans, for example, 7% of the exams in children younger than 5 years, 8% of the scans in children 5 to 9 years, and 14% of the scans in children 10 to 14 years delivered a brain dose of 50 mGy or higher, the study team wrote.

Solid cancer risks were higher for girls than boys and were highest for scans of the abdomen and pelvis, with 26 to 343 projected cases per 10,000 scans in girls, and 13 to 15 cases per 10,000 scans in boys. This equates to one projected radiation-induced solid cancer from every 300 to 390 abdomen/pelvis scans in girls and every 670 to 760 abdomen/pelvis scans in boys.

High cancer risks were also seen for chest and spine scans in girls, with one case projected for every 330 to 480 chest scans and every 270 to 800 spine scans, depending on whether patients were older or younger than 5.

"The potential risk of leukemia was highest from head scans for children younger than 5 years of age at a rate of 1.9 cases per 10,000 CT scans," the authors reported. "If radiation doses from those CT scans parallel our observed dose distributions, approximately 4,870 future cancers (95% uncertainty limit, 2,640-9,080 future cancers) could be induced by pediatric CT scans each year."

Variable dose

Effective doses were highly variable as well, ranging from 0.03 mSv to 69.2 mSv per scan. And the high doses were unfortunately common, with effective doses of 20 mSv or more delivered by 14% to 25% of abdomen/pelvis scans, 6% to 14% of spine scans, and 3% to 8% of chest scans. Nearly one-fourth of children with a single abdomen/pelvis scan received a dose of 20 mSv or higher.

"What we found that was surprising to me was that if you can reduce the top 25% of doses, you can reduce the number of cancers by 43%," Miglioretti said.

But how could radiation dose be so high at Kaiser Permanente and other large controlled healthcare organizations? Miglioretti said she could speculate on any number of causes for the higher doses in some studies.

"Unfortunately, we don't know because we didn't look into it," she said. "Maybe they didn't lower their parameters for the [pediatric patient], but we found wide variability even for adults, so that's not the only issue. Patient size matters, so they should be adjusting the parameters based on even a small child versus a large child."

The high overall dose levels are also due to increasing use of higher-dose CT exams such as abdomen/pelvis scans, as well as the wide variability of doses delivered for each exam, the group noted.

Harms of radiation

There is increasing evidence of harm for those receiving high doses of radiation, especially the youngest patients. Two recent observational studies, one from Australia and one from the U.K., confirmed that receiving a CT scan appears to increase the risk of cancer in later life.

In the U.K., the Life Span Study found a "direct association between pediatric CT and increased risk of both leukemia and brain cancer of similar magnitude." Children who received a cumulative brain dose of 50 mGy or more were at 2.8 times greater risk of brain cancer, and children who received an active bone marrow dose from CT of 30 mGy or more were at 3.2 times greater risk of leukemia (Lancet, August 4, 2012, Vol. 380:9840, pp. 499-505).

In the present study, 7% to 14% of head scans delivered doses of 30 mGy or higher from a single scan, the authors wrote, adding that many children receive multiple CT scans.

Implementation of readily available dose-reduction strategies, combined with the elimination of unnecessary imaging, could dramatically reduce future radiation-induced cancers from CT use, the study team concluded.

ACR weighs in

Commenting on the paper, the American College of Radiology (ACR) urged parents not to avoid necessary medical imaging for their children based solely on a study showing radiation risk from pediatric CT scans. The organization recommended that parents discuss the risks and benefits of any procedure with the child's physician and factor the information into their joint decision-making.

"Medical imaging exams are directly linked to greater life expectancy, declines in mortality rates, and are generally safer and less expensive than the invasive procedures that they replace, such as exploratory surgery," ACR wrote on June 7. "Diagnostic scans reduce the number of invasive surgeries, unnecessary hospital admissions, and the length of hospital stays."

CT scans are most often performed on children following trauma to the head, neck, or spine; these patients may suffer from neurological disorders or injury and need fast and accurate evaluation for life-threatening issues, including complications from chest infections and more. If an imaging scan is warranted, the immediate benefits outweigh a very small long-term risk, ACR stated.

For imaging professionals, the organization encouraged the use of ACR Appropriateness Criteria, participation in the ACR Dose Index Registry, and rigorous adherence to "child-sized" protocols. ACR also urged parents to maintain records of their children's scans.

Miglioretti agreed that "parents need to understand that when an exam is medically necessary, when CT is important for the management of the child, then these risks are very small and the benefit of the CT would usually outweigh the small risk."

"We don't want to scare patients or parents away from giving their child a CT when it's needed," she said, "but ... if parents are concerned about radiation, they should also talk to their physician and say 'hey, is this exam really needed?' " Maybe a nonradiation-bearing exam would work as well.

"I think parents are reasonable, and I think if a child needs this test, it's a very small increased risk at the patient level," Miglioretti said. "These numbers are really for a population, so if any one individual is going to benefit from CT, the risk is so minimal that it's not going to outweigh the benefit."

Miglioretti's group plans to continue the research by following individual patients over time.

"We have a unique data resource here with the HMOs that collect all the information on their patients, so we just submitted a grant proposal to follow these patients and see if they are actually at increased risk," she said.

The aim is to see if the increased cancer risk found in the recent observational studies from Australia and the U.K. hold up in a study that uses actual CT radiation dose levels, she said.