When Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) was alerted that two bombs had exploded near the finish line of the Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013, its emergency personnel immediately prepared to receive severely and moderately injured spectators and runners.

In a paper published online July 15 in Radiology, BWH staff details the hospital's response on that fateful day and how it has improved some operations and procedures to better handle emergency situations in the future.

"Overall, I think we were extremely proud of how we were able to take care of these patients and we felt things went very smoothly," senior study author Dr. Aaron Sodickson, PhD, BWH's emergency radiology director, told AuntMinnie.com. "At the same time, you always want to look at your practice and try to do even better the next time."

The first patient arrived at the level I trauma center just 19 minutes after the first explosion near the marathon's finish line; a total of 40 patients were seen at the hospital within 24 hours after the blast. Eighteen came to the emergency room (ER) in the first hour and 34 individuals arrived within three hours, wrote lead author Dr. John Brunner, an emergency radiology fellow at BWH, and colleagues (Radiology, July 15, 2014).

Patients had sustained moderate to life-threatening injuries from two pressure-cooker bombs that jettisoned ball bearings and other metallic objects, causing fractured bones, burns, and vascular injuries.

BWH's emergency radiology team helped triage the incoming wounded, facing the immediate challenges of gathering more staff, making imaging equipment available, ensuring smooth order-entry workflow, and communicating effectively with all caregivers and other colleagues.

Turnaround time

To assess the response, Brunner and colleagues compared turnaround times from routine emergency radiology operations with the performance in the aftermath of the marathon bombing.

Of the 40 patients received by BWH, 31 (78%) underwent diagnostic imaging. A total of 149 imaging scans were ordered, with x-ray accounting for the bulk of the exams (119, or 80%), followed by CT (30, or 20%). There were no emergency department orders for MRI or ultrasound.

Of the scans ordered, 57 x-ray studies were completed on 30 patients and 16 CT scans were performed on seven patients. Because several orders were for multipart CT examinations, this corresponded to 28 unique CT exams performed on seven patients.

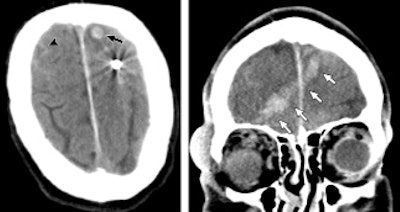

CT images of a 65-year-old man who sustained penetrating neurologic trauma from a ball bearing. Noncontrast CT (left) reveals a spherical metallic density lodged in the left frontal lobe with subarachnoid (arrowhead) and intraparenchymal hemorrhage (arrow). Coronal reformation (right) shows intracranial hemorrhage along the ball bearing's path from the right orbit through the right frontal lobe to the left frontal lobe (arrows). Images courtesy of Radiology.

CT images of a 65-year-old man who sustained penetrating neurologic trauma from a ball bearing. Noncontrast CT (left) reveals a spherical metallic density lodged in the left frontal lobe with subarachnoid (arrowhead) and intraparenchymal hemorrhage (arrow). Coronal reformation (right) shows intracranial hemorrhage along the ball bearing's path from the right orbit through the right frontal lobe to the left frontal lobe (arrows). Images courtesy of Radiology.Among the findings in the BWH review was a slowdown in x-ray completion time. The problem was not in image acquisition, but rather in having to route the images through the facility's lone single-plate x-ray reader. The bottleneck lengthened x-ray completion time to 52 minutes, up from 31 minutes under routine emergency x-ray conditions.

"That was a bit unexpected," Sodickson said. "Normally, we have no problem whatsoever getting x-rays done and read very quickly. In this case, once our department heard we had a large influx of patients coming, we brought additional portable x-ray units up to the ER."

Since then, BWH has switched to portable digital radiography devices, so images are immediately transmitted wirelessly to the hospital's PACS. "Not only do we save time for routine imaging, we have no bottlenecks if we are trying to image with more units," he said.

BWH had better success with patients undergoing CT scans. The hospital stationed a radiologist at each of its three available CT scanners for protocol and image review. CT exam completion times were reduced to 37 minutes with the additional staff, compared with 72 minutes under routine emergency situations.

"Normally, we read these [CT] studies off of the PACS, but here we wanted to really get those initial results to the team immediately," Sodickson said. "[We decided to] keep a radiologist at each CT scanner and deliver the images hot off the presses before the patient leaves the CT suite. Even the written turnaround time is a little bit misleading, because we had almost instantaneous medication and CT results."

Reducing redundancy

When preparing for a rapid influx of patients, it is crucial to design a "clear system for identification of unknown patients and to streamline the order-entry process to reduce confusion and order duplication," the authors wrote.

After the marathon bombing, BWH's system for naming unidentified patients contributed to a large number of duplicate orders. Of all 149 imaging orders, 42 requests (28%; 32 x-ray and 10 CT) were canceled because they were duplicate orders for the same patient from different physicians.

There was some confusion "because many patients were named 'unidentified,' " Sodickson said. "So the emergency medicine operations group came up with a new naming scheme for these patients."

The hospital's new system uses a unique color, gender, and number combination for each unidentified patient. For example, an unknown ER arrival might become "Crimson Male 12345."

BWH's evaluation also found that handwritten "concise summaries of key findings" from a PACS can be just as effective as a full report in determining the immediate needs of a patient.

"What you need in this situation is to focus on the acute findings that are going to change the patient's management, and you can sort out all the minutia later," Sodickson advised.

With this in mind, BWH has crafted carbon-copy pads of paper that radiologists can use to write down their preliminary findings, document their communications, and dictate their reports at a later time.

"That way we have a nice paper trail and documentation, and we can focus our attention more acutely on the immediate imaging needs," he said.

Dedicated radiology team

Sodickson said he hopes other healthcare facilities can learn from BWH's experiences and actions.

Most of all, it is "incredibly helpful and beneficial to have a dedicated emergency radiology team to handle these sorts of events, as well as routine emergency imaging," he said. "An event like [the Boston Marathon bombing] really highlights the value of that sort of system."

BWH's dedicated emergency radiology team has been in place for the past 10 years. The unit includes one attending physician 24/7, a second attending physician onsite from 6 p.m. to 3 a.m., and two fellow shifts and two resident shifts variably distributed throughout the 24-hour cycle.

"I know it's a plug for emergency radiology, but I have no idea how one could efficiently manage a mass casualty event like this if there were different radiologists from multiple groups within the hospital responsible for different components of the same patient's imaging," Sodickson said. "That is not a model that lends itself well to this kind of event."