PET/MRI could be an invaluable tool for evaluating how patients with large vessel vasculitis respond to treatments, suggests researchers in Scotland.

A team led by Dan Pugh, MD, of the University of Edinburgh reported that F-18 FDG-PET/MRI achieved what no other available imaging approach can do: It distinguished active from inactive disease and tracked disease activity over time.

“There is an urgent, unmet need for an imaging modality that can accurately and safely monitor disease activity longitudinally,” Pugh and colleagues wrote. The study was published August 25 in Nature Communications.

Large vessel vasculitis (LVV) is the most common primary vasculitis and is characterized by chronic inflammation of medium and large arteries, such as the aorta. Left undiagnosed, the condition can lead to organ damage, blood clots, and aneurysms, the authors explained.

While PET/CT is currently most commonly used to diagnose the disease, no available imaging modality can reliably monitor disease activity and treatment response throughout the disease course, they noted.

To explore the use of PET/MRI for this purpose, the group enrolled 24 patients with suspected LVV for an observational study between July 2019 and February 2022. All patients underwent baseline scans and then follow-up scans six months later. Patients were undergoing treatments with glucocorticoids, primarily prednisone to reduce inflammation.

The investigators developed a novel PET/MRI scoring system to assess patients for LVV that incorporates both PET and MRI metrics, the Vasculitis Activity using MR and PET (VAMP) score. The VAMP score combines PET metrics (mean standard FDG uptake values [SUVmean]) from 12 arteries with the presence or absence of increased T2-weighted mural signal on MRI.

Based on clinical assessments, 17 of 24 patients (71%) had active LVV at the time of baseline PET/MRI scans and six of 16 (38%) had active disease at follow-up.

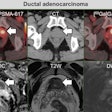

Panels A-C are images obtained at baseline. Panels D-F are images obtained from the same participant at follow-up. Panels A and D show T1-weighted MR images, panels B and E show attenuation-corrected PET, and panels C and F show fused PET/MR images. Image courtesy of Nature Communications.

Panels A-C are images obtained at baseline. Panels D-F are images obtained from the same participant at follow-up. Panels A and D show T1-weighted MR images, panels B and E show attenuation-corrected PET, and panels C and F show fused PET/MR images. Image courtesy of Nature Communications.

According to the findings, the VAMP score reliably discriminated active from inactive disease among patients (3.9 vs. 0.9, p < 0.0001). When applied to the longitudinal cohort as a whole, VAMP scores fell significantly from baseline to follow-up (4.6 vs. 1.7, p = 0.003).

In addition, when the researchers included only those patients who were considered to have clinically active disease at baseline and inactive disease at follow-up (n = 8), VAMP scores fell from 4.2 to 0.9 (p = 0.002), the group reported.

“Our data suggest that PET/MRI has the potential to become a useful disease-monitoring tool in patients with LVV,” the group wrote.

Ultimately, access to PET/MRI remains clinically limited, the authors noted. Presently, however, the approach could be an invaluable research tool for evaluating novel treatments for LVV, an important consideration given that there are a large number of emerging candidate therapies, they suggested.

“Based on our findings, larger, prospective studies assessing PET/MRI in LVV are now warranted,” the researchers concluded.

The full study is available here.