SPECT imaging has uncovered abnormal cerebral blood flow in retired professional football players in brain regions associated with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease, according to a poster presentation at last week's Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) meeting.

Among 20 former National Football League (NFL) defensive backs, SPECT showed significantly decreased blood flow in the medial frontal region, which is associated with executive function. Both defensive backs and 25 retired NFL offensive linemen in the study experienced reduced blood flow in the medial temporal region, which is associated with memory function. Both sets of regions are abnormal in dementias such as frontal temporal dementia and Alzheimer's.

Lead author Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD, a radiology resident at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), said it is "reasonable to conclude" that repeated hits to the head while playing football are a form of traumatic brain injury and caused the changes in regional cerebral blood flow.

'American institution'

Raji grew up in western Pennsylvania as a Pittsburgh Steelers fan, where football is "a way of life," he said. So it was rather natural for him and his colleagues to investigate the effects of traumatic brain injury in football players.

"Football is an American institution, and there is a big concern for the safety and health of NFL players," Raji said. "If we can establish what is going on with this group, hopefully we can combine the findings and apply them to other sports as well."

Traumatic brain injury among football players is somewhat unique in that athletes are exposed to chronic, repetitive hits to the head over time, rather than a single event, such as what might occur in a car accident or an explosion in a military conflict.

"What we wanted to do with this study was look at the abnormalities on brain SPECT, which looks at blood flow," Raji said. "Our specific interest was to see if we could identify abnormalities in a quantitative fashion when comparing our NFL cohort with a normal control population."

The data came from retired NFL players who were previously scanned and studied at the Amen Clinics, a private corporation that uses brain SPECT to evaluate traumatic brain injury patients. The Amen Clinics recruited these former athletes for several research studies.

Raji and colleagues reviewed 70 subjects, including 45 retired professional football players ranging in age from 26 to 82 (mean age, 57 years). The former athletes were compared with a control group of 25 male nonplayers, ranging in age from 19 to 84, who were studied under identical conditions.

The subjects underwent technetium-99m (Tc-99m) hexamethyl propylene amine oxime (HMPAO) SPECT with a three-headed gamma camera as they performed an attention-focusing cognitive task. The regional cerebral blood flow patterns of the players and controls were analyzed by NeuroQ quantification software that was developed at UCLA and is currently licensed to Syntermed for commercial marketing.

NeuroQ is designed to divide the brain into approximately 50 regions to determine degrees of abnormality compared to a normal population.

"This is important because we want to apply quantitative imaging to an individual patient to have personalized medical data," Raji said. "We then combined all the different abnormal regions across all the players and compared them to the normal group."

Significantly reduced blood flow

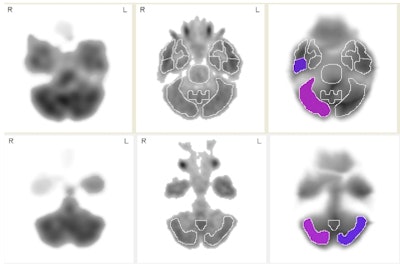

In the comparison of retired players to normal subjects, Raji and colleagues found significantly diminished regional cerebral blood flow in the right inferior lateral posterior temporal cortex and right cerebellum, and significantly elevated regional cerebral blood flow in the right posterior medial temporal cortex and right sensorimotor cortex. Defensive backs had lower blood flow compared to offensive linemen in the left superior frontal cortex.

SPECT images show axial slices from a group of 45 retired NFL players compared to 25 normal controls. Purple and violet regions show increasingly abnormal areas of low blood flow (violet represents a larger deficit in blood flow than purple) in the cerebellum and right medial temporal cortex. The medial temporal cortex is frequently implicated in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Image courtesy of Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD.

SPECT images show axial slices from a group of 45 retired NFL players compared to 25 normal controls. Purple and violet regions show increasingly abnormal areas of low blood flow (violet represents a larger deficit in blood flow than purple) in the cerebellum and right medial temporal cortex. The medial temporal cortex is frequently implicated in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Image courtesy of Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD.The most striking finding was the abnormally low areas of blood flow in the right posterior temporal lobe of the retired football players compared to normal subjects, Raji said.

"The temporal lobe finding is especially important because that's the area that often shows early abnormality in dementias, such as frontal temporal dementia or Alzheimer's," he explained. "That is relevant to this study because, even though none of our players had these dementias, traumatic brain injury is a risk factor for dementia."

The areas of regional cerebral blood flow abnormality also correlated with cognitive scores. In other words, low areas of blood flow in a particular area of the brain, such as the temporal lobes, correlated with overall decreased cognitive function.

"Those cognitive scores were not abnormal enough to be considered in the dementia range, but if you follow these patients over time, it is possible that what we are detecting could be predictive of some future decline," Raji said. "A longitudinal study will be the best way to assess that."

The subjects in the study are followed up every six months with the goal of better understanding the effects of contact sports.

"The bottom line is that your brain has the consistency of soft butter, and your skull is very hard with multiple bony ridges," Raji said. "You can imagine that any process that causes you to have contact or engage in contact activity potentially may be bad for the brain."