Buoyed by a five-year, $15.5 million grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), a consortium of researchers has embarked on an ambitious trek to revolutionize PET imaging with the world's first total-body scanner, a system that would employ a half-million PET detectors.

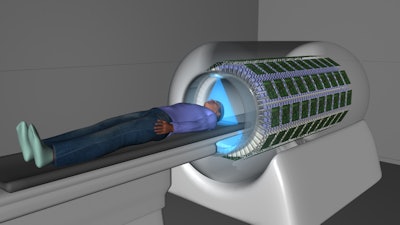

The Explorer project is designed to create a high-sensitivity PET device that would image an entire human body simultaneously, using a line of detectors that runs the length of the scanner bore, as opposed to conventional PET scanners that image 20-cm segments at a time.

The project's goals include building a device to reduce a patient's radiation dose by a factor of 40 and to decrease scanning time from 20 minutes to 30 seconds.

William Moses, PhD, senior staff scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

William Moses, PhD, senior staff scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory."We want to do something that is a bold step forward; we want something that could be a real game-changer," William Moses, PhD, senior staff scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, told AuntMinnie.com.

The total-body PET scanner is the latest project in Berkeley Lab's PET-related research, and it comes at a time when technology has advanced enough to make it possible to efficiently process the data generated from the proposed scanner's half-million detectors. Researchers from the University of California, Davis and the University of Pennsylvania are also contributing their expertise to the Explorer project.

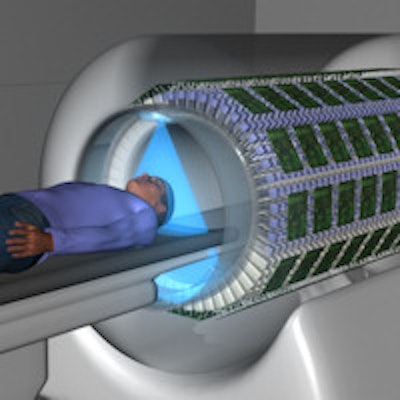

Moses is part of the team developing an electronic interface for the multitude of detectors, which would line the inside of the camera's bore.

Engineering challenges

Having a half-million detectors is "a great engineering challenge," Moses said, but the additional capacity means much less radiation dose to a patient, because the device would capture almost all available signal from radiopharmaceuticals.

"That can open up some applications that really we could not conceivably do before," he said.

He likened the blueprint design of Explorer to lining up eight conventional PET cameras. The electrical and mechanical details, such as how to cool the instrumentation, are among the chores to be finalized.

"Those are relatively straightforward engineering details," Moses said. "Once you have them all put together, we will deal with the vast amount of data that will be coming out of this camera, which will be generating terabytes."

The new configuration should also allow for significantly faster scan times.

"Certainly, motion correction would get much simpler, better imaging for patients who can't sit still for 20 minutes, and tracers could be taken up in smaller quantities," Moses said.

The Explorer total-body PET scanner is intended to deliver less radiation exposure and faster scan times. Image courtesy of the Explorer project.

The Explorer total-body PET scanner is intended to deliver less radiation exposure and faster scan times. Image courtesy of the Explorer project.Ready-made parts

One advantage for the Explorer project is that much of the PET technology needed to create the total-body camera, such as the detectors, electronics, and other instrumentation, is already available.

"We should be taking advantage of that," Moses said. "Why should we reinvent the wheel? We will get it done faster and probably more reliably if we make use of existing components."

To that end, the researchers have been in discussions with all of the major PET manufacturers to determine which company's technology would most benefit and align with Explorer's design goals.

"We have worked out what questions need to be answered by the manufacturers; neither the questions nor the answers are always black and white," Moses said. "In reality, we will have to work with just one company because we are looking mostly for detector modules and electronics. They come as a package. One person's electronics is not necessarily going to work on the other person's detectors."

While the researchers will need to be cognizant of intellectual property, the greater altruistic goal is to make the device as broadly available to as many patients as possible.

"We would not want to do something that is too limiting," he added. "If the planets align properly, [manufacturers] would be interested in commercializing what we do."

Qiyu Peng, PhD, a biomedical engineer at the Berkeley Lab, is assisting on the electronic instrumentation, along with Dr. Bill Jagust, a professor of public health and neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health, who has used PET for clinical neurology research and serves on Explorer's advisory board of medical doctors.

Major milestone

The hope is that a prototype can be developed in the next two years, with the construction of the camera taking the better part of one year.

"The most major milestone is that we would like to have the camera built two years from now, because the real question is: What applications can it be used for that we can't do right now?" Moses said. "Getting it into the hands of physicians is an extremely high priority for us."

At a 2013 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) medical imaging conference in South Korea, the researchers cited clinical applications for the total-body scanner in oncology, inflammation, infection, and cellular therapy, as well as for drug development, toxicology, and biomarker research. With the lower radiation dose to patients, PET also could be expanded in pediatrics, general biology, and chronic disease where multiple scans are often necessary.

"If we build this one camera, and it is the only one ever built, in many ways we would consider that to be a failure," Moses said. "Hopefully, this camera will do wonderful things, and it will be accessible to a large part of the patient population."