Using functional MRI (fMRI) and a clever experimental design, California researchers have shown that the experience of being left out activates the same brain machinery as being physically hurt. They published their results in Science (October 10, 2003, Vol. 302:5643, pp. 290-292).

"There's something about exclusion from others that is perceived as being as harmful to our survival as something that can physically hurt us," said Naomi Eisenberger, the lead author and a social psychology doctoral candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles.

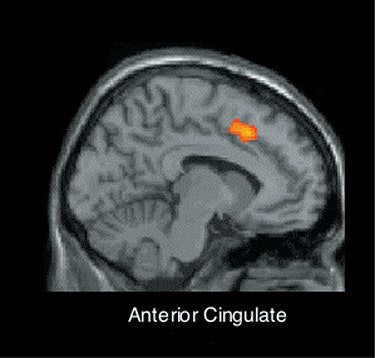

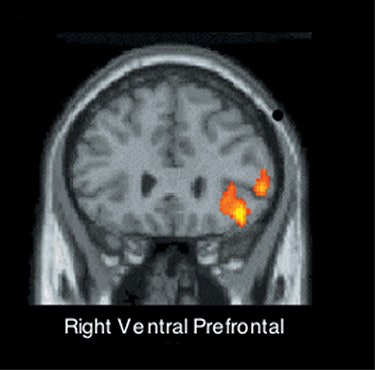

The areas in question are the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the right ventral pre-frontal cortex (RVPFC), Eisenberger said.

The ACC’s functions in pain are "pretty well-known," Eisenberger told AuntMinnie.com. It appears to be associated with the distress of pain, acting as a kind of alarm system to call attention to pain.

Indeed, she said, it is known that creating lesions in the ACC can help patients with severe chronic pain; they still feel the pain, but they are no longer bothered by it.

The RVPFC, on the other hand, seems to act as a governor, partly regulating the ACC and easing the feeling of pain when it’s active, Eisenberger said.

It has also been shown that rats whose ACC is stimulated emit what are called "distress vocalizations" -- usually only heard when the animal is separated from its social group, she said.

So it made sense to try to see what happens when someone is snubbed or left out of a game -- a difficult task, given that subjects are lying in the MR scanner and not usually interacting with a social group, Eisenberger explained.

Then Eisenberger and her co-author, Matthew Lieberman, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology at UCLA, attended a lecture by their third co-author, Australian psychologist Kipling Williams, Ph.D., of Macquarie University in Sydney. The latter described a virtual ball game he called "cyber-ball."

The game is simple: the subject has a controller and a pair of goggles, connected to a computer, that display an arm (labeled with the subject’s name) and two on-screen figures (labeled with other names). The other figures toss a virtual ball back and forth and to the subject’s ‘arm.’ The subject can then throw it back.

In fact, the other figures are computer-generated, but the subject is told they are other people in another room.

It was "a perfect paradigm," Eisenberger said. The subjects could lie in the MR scanner and play the game, while the researchers recorded their brain activity. In the experiment, the 13 subjects were first told they could watch the game, but technical difficulties prevented them from playing.

The subjects were then allowed to play, but after a few rounds of tossing the ball -- in which all three players got a fair share of the action -- the computer-generated players stopped throwing the ball to the subjects.

This created strong feelings of rejection, Lieberman said. "We had people coming out of the scanners saying ‘Did you see what they did to me?’"

|

| The anterior cingulate cortex is active when registering the distress of being snubbed. |

Imaging was performed on a 3-tesla full-body scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI), with an upgrade for echo-planar imaging (EPI). The subjects’ head movements were restrained with foam padding and surgical tape placed across their foreheads.

High-resolution structural T2-weighted echo-planar images (spin-echo; TR = 4000 ms; TE = 54 ms; matrix size 128 x 128; 26 axial slices; 3.125-mm in-plane resolution; 4-mm thick, skip 1 mm) were acquired coplanar with the functional scans.

Three functional scans, each lasting two and a half minutes and spanning the dorsal-ventral extent of the ACC, were acquired (echo planar T2*- weighted gradient-echo, TR = 3000 ms, TE = 25 ms, flip angle = 90°, matrix size 64 x 64, 19 axial slices, 3.125-mm in-plane resolution; 4-mm thick, skip 1 mm.)

Subjects who were most upset about the snub had the highest level of activity in their ACC. Conversely, those who were least upset had high activity levels in their RVPFC, Eisenberger said.

|

| Subjects whose right ventral prefrontal cortex was more active reported less distress from exclusion. Images courtesy of Naomi Eisenberger and Matthew Lieberman, Ph.D. |

The pattern of activity was "very similar" to that seen in studies of physical pain, she said, implying that the two types of discomfort share a common anatomical basis.

In an accompanying commentary in Science, Bowling Green State University psychologist Jaak Panksepp, Ph.D., said Eisenberger’s research is a first step toward gaining a better understanding of basic human emotions, such as love.

"A reasonable working hypothesis is that social feelings, such as love, are constructed partly from brain neural circuits that alleviate the feelings of social isolation," he said. But he cautioned that such speculations would remain in the realm of theory "until they are supported by solid research such as that carried out by Eisenberger and colleagues."

"Throughout history, poets have written about the pain of a broken heart," Panksepp added. "It seems that such poetic insights into the human condition are now supported by neurophysiological findings."

Eisenberger suggested that the research results might have near-term applications for understanding how and why people differ in their emotional responses to events -- why one man’s devastating social trauma is laughed off by another.

"It may be that some people just have a more sensitive system," she said. "For them pain hurts more and rejection feels more hurtful."

In the long run, this and similar experiments could shed light on the condition of chronic pain, whether or not it has an obvious physical cause, Eisenberger said.

By Michael SmithAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

October 24, 2003

Related Reading

Groups back move to boost pain research, training, September 25, 2003

Physician group to release online pain management text, September 9, 2003

Brain MR scans validate individualized pain ratings, July 8, 2003

PET scans confirm that your pain really is like no other, March 12, 2003

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com