Researchers from Canada have developed a new augmented reality software that uses a motion-tracking device to display patients' medical images -- such as from CT or MRI exams -- directly onto their body, even as they move.

Referred to as ProjectDR, the working prototype of the motion-tracking device consists of infrared cameras, a projector, and markers placed on fixed areas of the patient's body. Once images are obtained and the device is set up, the software automatically tracks the patient's position and projects the images accordingly.

"People naturally have anatomical variations, so having a means of viewing the patients' data directly on their body gives the clinician a lot more context to work with," Ian Watts, who developed the software, told AuntMinnie.com. Watts is a computing science graduate student at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

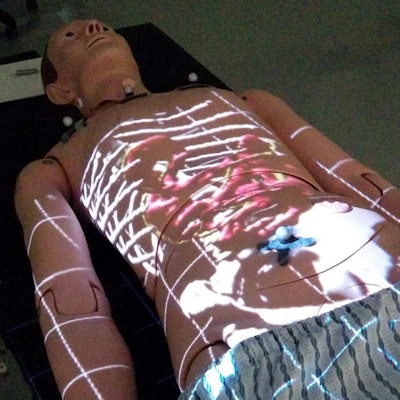

Medical images displayed on a mannequin using the augmented reality technology of ProjectDR. All images and video courtesy of Ian Watts.

Medical images displayed on a mannequin using the augmented reality technology of ProjectDR. All images and video courtesy of Ian Watts."The difference with this technology is that, whereas projectors typically project images on a flat surface, ProjectDR is able to do so on curved surfaces using a laser that keeps the image always in focus," said Pierre Boulanger, PhD, co-supervisor of the project at the university. "And when the patient moves, the device will compensate automatically."

'Realistic projection'

The concept for ProjectDR arose when project co-supervisor Greg Kawchuk, PhD, noticed the frequency with which medical clinicians needed to press and palpate on the body of patients during physical rehabilitation. Chiropractors, in particular, regularly pushed and prodded select areas on patients while attempting to define exact locations for treatment.

The augmented reality device consists of infrared cameras, markers that are placed on the patient, and a projector.

The augmented reality device consists of infrared cameras, markers that are placed on the patient, and a projector.To facilitate chiropractic training, the researchers began developing software to help guide finger movement via projections onto the patient's body. While working on this project, they realized that their idea could also be beneficial in the operating room -- especially for laparoscopic surgeries.

"We understood how difficult it could be in the operating room even for clinicians to know the precise location of parts underneath the skin," Boulanger said. "We believed that a realistic projection of images onto the patient could help the entire surgical team be able to see what's going on."

The main components of ProjectDR are a projector, infrared cameras (OptiTrack, NaturalPoint), and round markers (0.2 cm to 1.0 cm in size) that are covered with paint capable of reflecting infrared light. The projector and cameras are situated around the area the patient would be, such as an examination table, and the markers are attached to easily identifiable anatomical landmarks on the patient.

Once the device is set up and the markers placed, the researchers' proprietary software is able to automatically track the patient's movements and project his or her internal anatomy onto the appropriate part of the body for 3D visualization.

For proper calibration of the augmented reality images, the patient needs to have a few markers affixed to predetermined anatomical landmarks on the body during image acquisition. The location of the markers is recorded on the images, and the software is thus able to align the images with markers on the patient's body during projection.

Furthermore, ProjectDR can display any type of image that is saved in DICOM format and then loaded into the computer software, Watts said. Once uploaded, the images undergo volume rendering for 3D volume reconstruction, as well as transfer-function editing for opacity enhancement and color application.

"ProjectDR also has the capacity to present segmented images -- for example, only the lungs or only the blood vessels -- depending on what a clinician is interested in seeing," he said.

ProjectDR enables users to display CT or MR images directly on a moving object.

Boundless applications

"This projected augmented reality provides a common perspective that is not tied to an individual point of view, which can be used by others such as a surgical team," Boulanger said. "The software can easily function with other display technology and has many potential applications including in education, surgical planning, laparoscopic surgery, and entertainment."

Surgical planning is currently the most practical application due to its interactive nature and because planning doesn't need to be quite as precise as actual surgery, he said. A prime example is preparing for breast reconstruction surgery; surgeons can use the augmented reality projection to compare possible changes to the breast before deciding how they would like to modify it.

For minimally invasive or image-guided surgeries, using ProjectDR could allow clinicians to look straight at a point of interest with a kind of "x-ray vision," instead of having to refer to a screen, he noted. They could also track the entry point of an endoscopic tool and see it as a graphic as it enters the patient's body.

Watts and colleagues have been working on improving various technical aspects of ProjectDR to make it suitable for testing with these types of procedures as well as for eventual commercialization. Their first priority is fine-tuning the device's ability to automatically calibrate the augmented reality images to the patient's body. They hope to move toward depth-based registration for alignment, as opposed to the anatomical landmark-based method currently in use.

"After completing necessary adjustments [to ProjectDR], we will conduct a pilot study later this year to test the viability of ProjectDR for teaching chiropractic and physical therapy procedures, as well as evaluate several of its real-life surgical applications in a surgical simulation laboratory," Boulanger said. "Testing has been limited to a mannequin so far."