Kaposi's Sarcoma:

Clinical:

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a lympho/angio-proliferative disorder

associated with proliferation of spindle cells and vascular

spaces. A virus in the herpes family has been identified as the

probable cause of KS- it is referred to as Kaposi's sarcoma

associated herpes virus or human herpes virus 8 (KSHV/HHV-8)

[2,5,8]. The incidence of Kaposi's has decreased in HIV patients

(found in about 15% of HIV patients)- probably due to the use of

antiretroviral therapy [5]. None-the-less, Kaposi sarcoma is the

most common malignancy observed with HIV infection [8]. The

overwhelming majority of cases (95%) of Kaposi?s sarcoma occur

in homosexual or bisexual men (M>F 20:1) [5,6]. As the HHV-8

virus is the causitive agent, it is common for KS patients to

also have coexistent HHV-8 associated Castleman disease [13].

The skin is most commonly involved in KS [9] and cutaneous lesions are seen in 66% of cases [12]. AIDS KS is more aggressive than the non-AIDS KS and the lesions often have a different distribution- occupying the nose, mouth, and genitalia [8]. Visceral involvement is seen in about 50% of AIDS-KS- most commonly involving the GI tract [8]. Pulmonary involvement in seen in 6-45% of patients with cutaneous disease and the disease is usually widespread by the time pulmonary involvement occurs [5,7,10,12]. Isolated pulmonary Kaposi?s without cutaneous manifestations is considered a rare event [5,9], although in one series of patients with bronchopulmonary AIDS-related KS, 15% did not exhibit mucocutaneous involvement [7].

Patients with KS generally have very low CD4 counts (below 100-200 cells/uL) and the tumor becomes more aggressive with increasing immune impairment [2,10]. Patients typically present with cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and fever- still, it is important to note that approximately two-thirds of patients with known KS who present with new onset pulmonary findings actually have a co-existing, usually treatable, infection, rather than spread of their malignancy [1]. Both endobronchial and transbronchial biopsy have a diagnostic yield of 26-60% [5]. Open lung biopsy has a yield of about 50% and is rarely performed [5]. Without treatment, patients with pulmonary Kaposi?s sarcoma have a median survival of only a few months [5]. Treatment for KS consists of combination chemotherapy. Although response is generally good, relapse is frequent [5].

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has resulted in a substantial diminution in the incidence, morbidity, and mortality of KS [6]. HAART alone can lead to stabilization and regression of KS [6]. Initiation of HAART can sometimes result in an initial worsening of KS (KS-associated immune reconstitution syndrome) [6].

X-ray:

Plain film: Thoracic KS can first be detected along the central bronchovascular interstitium where is produces apparent bronchial wall thickening- unfortunately KS is rarely diagnosed at this stage. Pulmonary involvement is characterized by multiple areas of ill-defined nodular density (1 to 2 cm in size), coarse linear opacities (interlobular septal thickening in 40%), or areas of flame-shaped or ill-define nodular consolidation in a perivascular distribution- particularly in the mid and lower lung zones. A pleural effusion is found in over 50% of cases (often bilateral) and adenopathy can be seen in 10-65% of patients. Adenopathy, although present, is not characteristically the dominant feature of the disorder and bulky adenopathy is extremely uncommon (and suggests another diagnosis such as TB or MAC).

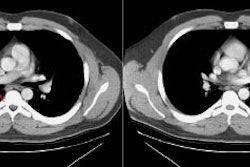

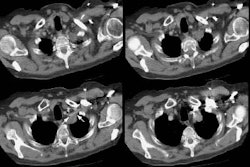

Computed tomography: Findings include bronchial wall thickening (bronchovascular thickening), often associated with subtle thickening of the interface with the lung parenchyma due to tumor infiltration. A characteristic CT finding is poorly marginated, symmetric nodular bronchovascular ("flame shaped") infiltrates usually exceeding 1cm radiating from the hilum [7]. Spiculated nodules (1-2 cm and tend to coalesce) have also been described as a common finding on HRCT [2,6]. Areas of ground glass attenuation surrounding one or more nodules can be seen [6]. There can be areas of consolidation and pleural effusions are present in 35-60% of cases [6]. The presence of pleural collections has been associated with shortened survival times [7]. Adenopathy (axillary, mediastinal, and hilar) can be seen in 33-53% of patients and it is generally less than 20 mm in diameter [6].

Scintigraphy: Kaposi's sarcoma is usually thallium positive and gallium negative in patients with no superimposed opportunistic pulmonary infection (Sensitivity about 90%). Lymphoma is generally positive on both examinations; but this may also be seen with TB or MAI infections, and in Kaposi's patients with a superimposed opportunistic pulmonary infection. Infection is usually gallium avid, but thallium negative. Thallium uptake may uncommonly be seen in association with certain pulmonary infections, however, the uptake is usually transient and delayed images will often demonstrate clearance of activity over time. Such clearance is typically not seen in association with thallium uptake in malignant lesions. This is most likely due to the different mechanisms of thallium uptake in neoplasms and inflammatory lesions. In inflammation, thallium accumulation is most likely related to passive diffusion into the extravascular space- with time, the tracer will diffuse back to the intravascular component and be eliminated [3].

False negative thallium scans for Kaposi's have been described with bronchial Kaposi's. Parenchymal Kaposi's is detected much better and the use of SPECT imaging can enhance lesion detection [4]. Thallium has been used to differentiate Kaposi's sarcoma from malignant lymphoma in AIDS patients. Kaposi's sarcoma is usually thallium positive and gallium negative in patients with no superimposed opportunistic pulmonary infection (Sensitivity about 90%). Lymphoma is generally positive on both examinations; but this may also be seen with TB or MAI infections, and in Kaposi's patients with a superimposed opportunistic pulmonary infection. Infection is usually gallium avid, but thallium negative. Thallium uptake may uncommonly be seen in association with certain pulmonary infections, however, the uptake is usually transient and delayed images will often demonstrate clearance of activity over time. Such clearance is typically not seen in association with thallium uptake in malignant lesions. This is most likely due to the different mechanisms of thallium uptake in neoplasms and inflammatory lesions. In inflammation, thallium accumulation is most likely related to passive diffusion into the extravascular space- with time, the tracer will diffuse back to the intravascular component and be eliminated [3].

False negative thallium scans for Kaposi's have been described with bronchial Kaposi's. Parenchymal Kaposi's is detected much better and the use of SPECT imaging can enhance lesion detection [4].

REFERENCES:

(1) Annu Rev Med 1996; Murray JF. Pulmonary complications of HIV infection. 47: 117-126 (Review)

(2) Radiologic Clinics of North America 1997; McGuinness G. Changing trends in the pulmonary manifestations of AIDS. 35 (5): 1029-1082

(3) J Nucl Med 1996; Abdel-Dayem HM, et al. Evaluation of sequential thallium and gallium scans of the chest in AIDS patients. 37:1662-1667

(4) Nuclear Medicine Annual 1994; Abdel-Dayem HM, et al. Role of 201-Tl chloride and 99m-Tc Sestamibi in tumor imaging. 181-234 (p. 224) (No abstract available)

(5) Chest 2000; Aboulafia DM. The epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features of AIDS-associated pulmonary Kaposi?s sarcoma. 117: 1128-1145

(6) AJR 2007; Godoy MCB, et al. Imaging features of pulmonary kaposi sarcoma-associated immune reconstruction syndrome. 189: 956-965

(7) Radiographics 2006; Restrepo CS, et al. Imaging

manifestations of Kaposi sarcoma. 26: 1169-1185

(8) AJR 2011; Davison JM, et al. FDG PET/CT in patients with HIV.

197: 284-294

(9) Radiographics 2011; Kanne JP, et al. Beyond skin deep:

thoracic manifestations of systemic disorders affecting the skin.

31: 1651-1668

(10) AJR 2012; Lichtenberger JP, et al. What a differetial a

virus makes: a practical approach to thoracic imaging findings in

the context of HIV infection- Part I, pulmonary findings. 198:

1295-1304

(11) Radiographics 2014; Chou SHS, et al. Thoracic diseases

associated with HIV infection in the era of anti-retroviral

therapy: clinical and imaging findings. 34: 895-911

(12) Radiographics 2018; Javadi S, et al. HIV-related

malignancies and mimics: imaging findings and management. 38:

2051-2068

(13) AJR 2021; Glushko T, et al. HIV lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and important imaging features. 216: 526-533