The Role of CT in Staging Bronchogenic Carcinoma

Routes of Spread

The most common routes of metastatic spread of lung cancer are to the contiguous lymph nodes in the lung and mediastinum [19]. The peribronchial and segmental lymph nodes are commonly the first site of regional node metastases. These lymph nodes are within the visceral pleural envelope and are potentially resectable with an anatomic lung resection [20]. Metastases beyond the visceral pleura are next found in the ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal nodes. Metastases to mediastinal nodes can occur in the absence of hilar node disease due to the presence of direct lymphatic channels to the mediastinum [21]. Left upper lobe lesions can drain directly to the aorto-pulmonary window, left paratracheal node stations, or subcarinal nodes [20-22]. Right upper lobe lesions may drain to the right paratracheal chain [21,22] or left tracheal border [164]. "Skip metastases" (mediastinal nodal metastases without hilar metastases) are found in up to 30% of patients presenting with bronchogenic carcinoma and are though to occur more commonly in association with upper lobe tumors [21,200]. However, skip metastases can also occur with tumors in sites other than the right or left upper lobes [21]. Skip metastases are more commonly associated with adenocarcinomas [197] and are reported to have a more favorable outcome [200]. The possibility of skip metastases is the reason complete dissection of the regional mediastinal lymph nodes is essential during surgical resection even when there are no apparent hilar lymph node metastases [21].

Computed Tomography for the Detection of Pathologic Adenopathy in Bronchogenic Carcinoma:

Computed tomography (CT) is the mainstay of radiological imaging for the staging of bronchogenic carcinoma [23]. It is the role of the radiologist to define the anatomic extent of the tumor and assist the thoracic surgeon in deciding whether the tumor is potentially resectable or likely unresectable. The cross-sectional capabilities of CT allow evaluation of the hila and mediastinum for the presence of nodal metastases, as well as assessment for extrathoracic metastases. As CT is an anatomic exam, the presence of malignant nodes is based primarily upon size criteria. Several studies have examined the size of normal mediastinal lymph nodes which averages approximately 1 cm [24-26]. Size has been shown to vary depending on location within the mediastinum [24,25], and size may also vary depending on the prevalence of granulomatous disease in the geographic region and presence of underlying lung disease [26]. Lymph nodes within the mediastinum tend to be oriented vertically, the transverse plane of the CT scan generally records the width and not the length of the node [25,27]. Although not universally accepted, a short axis diameter in the transaxial plane greater than 1 cm is generally considered pathologic and indicative of tumor spread by CT [23,25,28; and other studies listed below]. By decreasing the size criteria by which a lymph node is considered pathologic, the sensitivity of CT becomes higher, but the specificity becomes lower [29]. Although the probability of metastases increases with increasing lymph node size [26,30], CT cannot reliably differentiate enlarged malignant mediastinal nodes from benign enlarged hyperplastic lymph nodes. Nor can CT detect the presence of microscopic tumor foci in lymph nodes of normal size-- an important limitation to bear in mind when 10% to 64% of all mediastinal nodal metastases occur in clinically normal lymph nodes [1,31-34].

Despite its limitations, CT does provide useful pre-operative staging information. It can provide a road map for the surgeon during mediastinoscopy to permit efficient nodal sampling and can also reveal possible involvement of nodes not accessible to mediastinoscopy that would require biopsy by other means [35].

It is important to remember that a CT scan is neither positive or negative for mediastinal lymph node metastases-- it shows either an enlarged node or a normal sized node [31]. If a node is enlarged, it must be examined pre-operatively. The decision to performed mediastinoscopy in the absence of CT abnormalities is affected by a number of factors including the surgical team involved, the patient's operative risk, the tumor cell type, and whether the presence of pathologic mediastinal nodes at mediastinoscopy is considered an indicator of unresectable disease.

Computed Tomography for Staging Hilar Lymph Nodes: N1

The anatomic pulmonary hilum is the

triangular depression on the mediastinal surface of the lung

through

which the bronchi and blood vessels enter. The radiologic

definition is

the opacity caused by the bronchi and blood vessels themselves

[22].

According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer

classification

scheme for nodal stations, the hilar nodes are classified as 10R

and

10L, more distal nodes are classified 11R/L through 14 R/L

(includes

interlobar, lobar, segmental and subsegmental nodes) [5].

Although

mediastinal nodes are clearly demonstrated on CT because they

are

surrounded by fat, the recognition of hilar nodes requires an

understanding of the normal appearance of the complex system of

arteries and veins in cross section [22]. Normal hilar lymph

nodes are

located in the interstitium between the bronchus and the

pulmonary

vessels (peribronchovascular interstitium). The distinction

between

normal nodes and the interstitium is difficult on CT, and this

area

typically appears as a hypoattenuating region adjacent to the

pulmonary

hilar vessels and bronchi [36]. Hilar nodes are most numerous at

bronchial bifurcations, and are often located between the major

bronchi

and the pulmonary vessels [22].

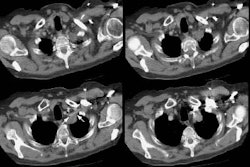

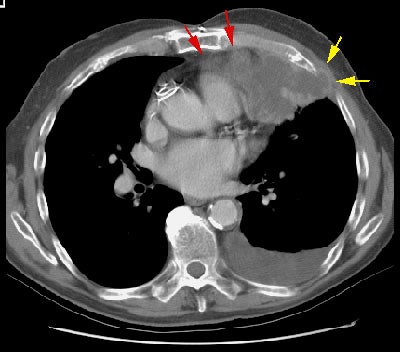

Example of the normal hilar interstitium: The images below are from a patient without bronchogenic carcinoma. The images demonstrate normal hilar lymphatic tissue (yellow arrow right image) which appears as a low density region between the bronchus and pulmonary vessel. A small calcified node is seen on the right (red arrow) in this patient with prior granulomatous disease. NOTE: Click image to enlarge.

Although the presence of metastases to ipsilateral hilar nodes will influence patient prognosis, their presence generally does not affect operability [37]. Because patient management is not affected, some authors feel that hilar nodes are unimportant [30]. Primarily as a result of this general feeling, there has not been an extensive evaluation of the accuracy of computed tomography for the evaluation of ipsilateral hilar adenopathy.

Using the standard 1 cm size criteria for the presence of metastatic hilar adenopathy, the sensitivity ranges from 17% to 89%, the specificity from 50% to 86% [30,37], and the accuracy from 20-68% [36]. Given that the accuracy of chest radiographs for the detection of hilar involvement has been reported to be between 61% to 71% [22], it would appear that CT does not contribute significantly to the detection of hilar adenopathy.

Recently it has been proposed that

with

the use of helical CT the standard criteria for abnormal nodes

(i.e.,

size greater than 1 cm) lacks sensitivity for the presence of

hilar

adenopathy [36]. The normal peribronchovascular interstitium

adjacent

to the hila contains lymph nodes and normally has a concave

or

straight margin with the adjacent lung parenchyma [38] and

this

finding is not affected by the level of pulmonary distention. By

using

the presence of a convex margin of the interstitium with

the

adjacent lung parenchyma to indicate the presence of hilar

metastases,

a sensitivity of 87% can be achieved (specificity 88%, and

accuracy

88%) [36]. This criterion has also been shown to have good

interobserver agreement. In another study of the

peribronchovascular

interstitium and hilar lymph nodes by spiral CT, it has also

been

suggested that a short axis diameter of greater than 3 mm be

considered

abnormal, but further studies have yet to confirm this criterion

[39].

A limitation of either of these criteria is that other

conditions can

also produce the presence of adenopathy with convex

bronchovascular

margins or increased transverse diameter including sarcoidosis,

bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, and interstitial fibrosis

[36].

New Criterion for Determination of Pathologic Hilar Adenopathy

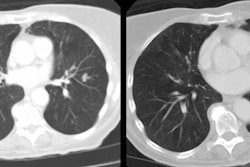

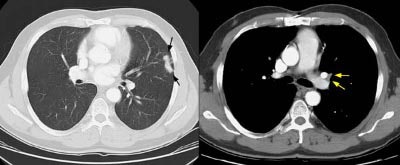

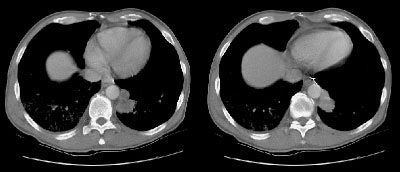

Example 1: This is an example of an N1 node in a patient with a lingular adenocarcinoma (left image). Although not pathologic by short axis size criteria, the lymphatic tissue in the left hilum has a convex border with the adjacent lung (white arrows). This node contained adenocarcinoma at histopathologic analysis. Some authors advocate using the presence of a convex margin of the interstitium with the lung parenchyma to indicate pathologic adenopathy to improve the sensitivity of CT for detecting hilar metastases [36].

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Example 2: This patient is an example of a false negative CT for hilar nodal metastases even when applying the suggested new criterion. The patient had a peripheral adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe (black arrows). The left hilar node (yellow arrows) is not pathologic by size criteria, nor does it exhibit a convex margin with the adjacent lung parenchyma. This is a normal node by CT, however, at histopathologic analysis the node was positive for malignant cells.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Computed Tomography for the Staging Mediastinal Nodes N2/N3:

The prevalence of mediastinal nodal metastases increases with increasing T-stage of the primary lesion [40]. For patients with metastases to mediastinal lymph nodes confirmed by mediastinoscopy, it is generally agreed that these patients do not benefit from primary surgical intervention and that a multimodality treatment plan, including induction chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, followed by potential surgery is preferred [7,15,16]. When N2 disease is discovered only at thoracotomy, however, the resection rate is higher (60-90%) and 5-year survival improved [6,7,15,18].

Despite widespread use for the staging of bronchogenic carcinoma, studies have demonstrated a wide variability in the sensitivity of CT for staging mediastinal nodes (See Table 1). Overall sensitivity and specificity for a transaxial short axis greater than 1.0 cm is 62% and 73%, respectively. Unfortunately, the positive predictive value of an abnormal CT scan is low. In one review 37% of lymph nodes that measured 2-4 cm in short-axis were hyperplastic and contained no tumor at surgery [30]. Also, patients with obstructive pneumonitis frequently have hyperplastic mediastinal nodes that exceed 1-2 cm in size and the specificity of CT decreases in these cases [27,30]. The negative predictive value of CT is also low. Studies have shown that between 7% to 64% of patients with no enlarged nodes visible on CT scans may have positive N2 nodes at surgery [1,33]. Interobserver agreement rates are good for determining T and N classification and stage in patients with lung cancer, however, agreement rates are lowest for assessment of mediastinal nodes [41].

When evaluation for N2/N3 disease is

specifically requested, mediastinoscopy should probably replace

CT,

using the CT or PET scan results as a road map [28].

Mediastinoscopy is

best suited for sampling lymph nodes in the pre- and

paratracheal

regions, but has limited access to nodes in the inferior and

posterior

mediastinum, and aortopulmonary window [182]. The procedure is

generally safe with a 2% risk of major morbidity and a 0.08%

mortality

[182]. Mediastinoscopy has a reported sensitivity of

approximately 78%

(others report 81-89% [202])

[199].Overall, mediastinoscopy is believed to have a

false-negative

rate of 11% [202]. Endobronchial ultrasound guided fine-needle

aspiration (EBUS) or

transesophageal endoscopic (EUS) ultrasound-guided fine needle

aspiration may be an alternative approach to mediastinal staging

[182,199]. Combined EBUS and EUS can reach almost all

mediastinal nodal

stations [199]. A randomized trial comparing surgical staging

(mediastinoscopy and/or left parasternal mediastinotomy) to

combined

EBUS/EUS found similar sensivities 79% versus 85%, respectively

[199].

A combination of EBUS/EUS followed by further surgical staging

of the

node negative patients increased the sensitivity to 94%- which

results

in fewer unnecessary thoractomies [199]. Overall, endosonography

is

associated with a lower complication rate (about 1%), does not

require

general anesthesia, is preferred by patients, and is considered

cost

effective when compared to surgical staging [199]. The false

negative

rate for VATS staging is reported to be approximately 7% [202].

The purpose of CT in the evaluation of T1N0M0 lung cancer is to eliminate needless thoracotomies [42]. There is a wide range of prevalence of mediastinal adenopathy in patients with T1 lesions reported in the literature- between 5% to 27% [30,35,40-44,157,175]. In patients with T1 cancer, CT has a sensitivity of only 27-41% for the detection of pathologic mediastinal nodes [175]. Features which would suggest an increased likelihood for mediastinal lymph node metastases include a solid lesion (as opposed to ground-glass), spiculated lesion margins, and bronchovascular bundle thickening in the surrounding lung [157]. Marked nodule enhancement during dynamic CT imaging (peak enhancement of 110 HU or greater or net enhancement of 60 HU or greater) has also been reported to be associated with an increased likelihood for nodal metastases (sensitivity 62-77%, specificity 70-89%, accuracy 71-83%) [168,175]. If the lung lesion demonstrates any of these features, a more extensive workup for mediastinal nodal metastases may be required [157].

Overall, the likelihood for

mediastinal

lymph node metastases in patients with T1/T2 squamous cell

carcinoma

without enlarged lymph nodes on CT is low [17]. In such cases,

surgical

resection may be anticipated, and pre-operative mediastinal

exploration

may not be necessary. In adenocarcinoma and large cell

carcinoma,

however, unexpected metastases were found in 18% of patients

without

enlarged lymph nodes on CT and mediastinoscopy was thus advised

in this

group of patients [17].

Examples of False-Positive and False-Negative CT Scans for Mediastinal Adenopathy

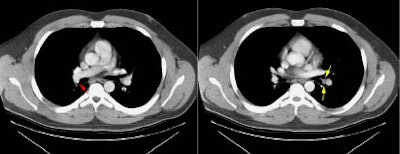

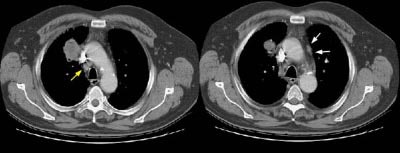

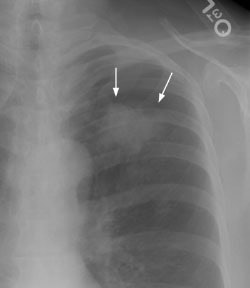

Example 1: False-positive exam -- this patient had a right upper lobe squamous-cell carcinoma. The mass is adjacent to the superior vena cava. Abnormal mediastinal N2 (yellow arrow) nodes were identified by the staging CT exam. Contralateral N3 nodes (white arrows) were borderline abnormal by size criteria. The patient underwent medianstinoscopy and anterior mediastinotomy (Chamberlain procedure) for pre-operative staging -- both of which were negative for malignant cells. The patient had underlying interstitial lung disease which has been associated with the presence of reactive mediastinal adenopathy. At surgery the patient was found to have ipsilateral hilar adenopathy (N1) and parietal pleural invasion (T3 tumor) or a stage IIIA.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Example 2: False-negative CT exam -- this patient had an adenocarcinoma in the right upper lobe that measured less than 3 cm in size (T1 lesion). The ipsilateral mediastinal nodes identified by staging CT were not pathologic by size criteria. The surgical team elected to proceed to thoracotomy without mediastinoscopy. At surgery, the small right paratracheal nodes which measured less than 1 cm where found to contain microscopic foci of tumor (N2 nodes). The patient was staged histopathologically as T1N2M0 (Stage IIIA).

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Computed Tomography in T-staging:

When the tumor is completely surrounded by lung, CT is very accurate in determining correct T-staging [31]. Post-obstructive atelectasis or consolidation make delineation of the primary tumor more difficult. Bolus contrast enhancement can aid in separation of the tumor from the consolidated lung. Collapsed lung typically enhances to a greater degree than the central obstructing tumor, due to an increased blood flow per unit area of atelectatic lung caused by crowding of the pulmonary vessels [45].

A very important contribution of CT in the staging of bronchogenic carinoma is the demonstration of findings which would proclude surgical resection. Certain findings have been demonstrated as being diagnostic of unresectable disease. These include encasement of the trachea or main pulmonary artery (or left or right pulmonary artery within 1 cm of its origin); encasement of the superior vena cava or aorta; invasion of a vertebral body; and metastatic disease to the contralateral lung or extrathoracic organs [40]. It should be emphasized that to classify a bronchogenic carcinoma as unresectable on the basis of CT findings, the findings must be unequivocal [40]. Up to 24% of patients that present with bronchogenic carcinoma may have unequivocal evidence of unresectability at CT staging -- thereby unnecessary surgery can be avoided in these patients [40]. In an additional 8% of patients, the extent of CT abnormalities coupled with their surgical risk, also result in their being classified as non-resectable [40].

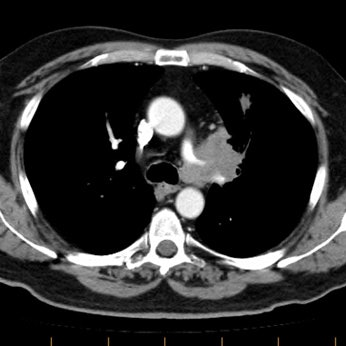

Example: The case below demonstrates extensive mediastinal involvement by the tumor with encirclement of the right inominate artery and superior vena cava. Such findings are felt to be unequivocal evidence of non-resectability. A metastatic lesion is also evident in the right aspect of the sternum.

Pulmonary Fissures:

Neoplastic extension through the interlobar fissures does not represent a contraindication to surgery, although more extensive resection may be required. Such information can be very useful if a thoracoscopic resection has been planned. Thin collimation scans (1 mm) with a high spatial frequency algorithm allow improved visualization of the major fissure and it's relationship to an adjacent neoplasm. The minor fissure is difficult to assess on axial images, but helical acquisition with thin collimation and multiplanar reconstructions can aid in the evaluation of a tumor near the minor fissure [99,108].

Computed Tomography for Visceral Pleural, Chest Wall, Mediastinal, or Vital Structure Invasion:

T3/T4 Chest wall invasion occurs in about 8% of

patients with a contiguous pulmonary malignancy [46,47]. Chest

wall

invasion does not necessarily preclude surgical resection as

long as

mediastinal lymph node involvement is not present. However, the

presence of chest wall invasion is important to document

preoperatively

as these patients will require en bloc chest wall resection

surgery

which is associated with a higher post-operative morbidity and

mortality rate [26,46,48,49].

CT findings which suggest visceral pleural invasion:

Visceral pleural invasion is results in increased

T-stage from T1 to T2 and upstages the tumor from stage IA to

stage 1B, even if it less than 3 cm in size [209]. When the

primary tumor is larger than 3 cm, visceral pleural invasion may

indicate a need for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage

IIA and selected patients with IB disease [210]. Visceral pleural

invasion has been shown to be an adverse prognostic factor in

patients with NSCLC [212]. Five year survival rates for patients

with surgically resectable NSCLC are 86%, compared to 62-70% for

patients with visceral pleural invasion, and 57% for patients with

parietal pleural invasion [210]. Visceral pleural invasion is

graded pl0 (no pleural involvement beyond the elastic layer), pl1

(pleural invasion beyond the elastic layer), pl2 (pleural invasion

to the visceral pleural surface), or pl3 (pleural invasion into

any component of the parietal pleura or chest wall) [209,211].

Patients with pl1 or pl2 have significantly worse survival

compared to patients with pl0 disease [209]. Detection and

determination of visceral pleural invasion by CT is challenging.

For tumors no abutting the pleural surface, the presence of a

pleural tag with a soft-tissue component at the pleural end on

mediastinal windows has been shown to be moderately associated

with visceral pleural invasion [210]. Overall, the presence of a

pleural tag is highly sensitive, but not a very specific predictor

of visceral pleural invasion [210].

For peripheral part solid nodules findings

associated with visceral pleural invasion include pleural contact,

pleural thickening, solid portion of greater than 50%, and nodule

size greater than 2 cm [212]. When all four variables are present,

the specificity for visceral pleural invasion is 99% [212]. For

pure ground glass nodules, the likelihood of visceral pleural

invasion is extremely unlikely, even when the lesion abuts the

pleural [212].

CT findings which suggest chest wall invasion include [46,50,51]:

(In general, two or more of the findings should be present to interpret the exam as positive)

1) Focal pleural thickening below

the

mass

2) More than 3 cm of contact between

the

mass and the pleural surface

3) An obtuse angle between the mass

and

the pleural surface

4) Encroachment on or increased

density in

the underlying extra-pleural fat

5) Obvious rib/bone destruction

6) Asymmetry of the chest wall soft

tissues adjacent to the tumor

7) Mass invading the chest wall

Unfortunately, the accuracy of CT in

the detection of chest wall involvement has not been very good

because

contact between the tumor and adjacent structures does not

necessarily

mean invasion [205].

The individual criteria used to define potential chest wall

involvement

are either highly sensitive, but non-specific, or highly

specific, but

insensitive [46]. Reported sensitivities for chest wall invasion

as

determined by CT findings are 38% to 87%, and specificities

range from

40% to 91% [46,50,52,205]. By itself, the clinical symptom of

focal

chest

wall pain has been shown to be more accurate for the

determination of

chest wall invasion with a sensitivity of 67% to 75% and a

specificity

of 85% to 94% [47,50,164]. Other authors report improved

sensitivity

and specificity by measuring a ratio between the length of the

arch of

contact the tumor has with the adjacent structure and the

diameter of

the tumor [205]. In one study, an arch-distance to tumor

diameter ratio

of greater than 0.9 has a sensitivity of about 90% and a

specificity of

96% for thoracic invasion [205].

Despite the general consensus that

chest

wall invasion is not well assessed by CT, it should be kept in

mind

that the above findings are clues to its presence and should not

preclude surgery for potentially resectable disease. The

findings

merely alert the surgeon to the potential for an en-bloc chest

wall

resection. The use of helical CT with reconstruction images may

improve

the ability of CT to assess chest wall invasion [53,54]. MR

imaging

has a sensitivity of 63-90% and a specificity (84-86%) for

diagnosing chest wall invasion [160].

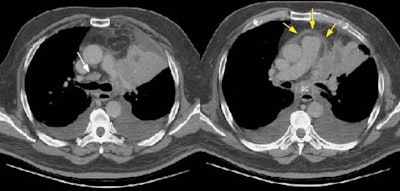

Example 1: This is a case of squamous cell carcinoma that was found to be invading the chest wall at surgery. CT findings which suggested the diagnosis of chest wall invasion in the case include focal pleural thickening below the mass, more than 3 cm of contact between the mass and the pleural surface, an obtuse angle between the mass and the pleural surface, and encroachment on or increased density in the underlying extra-pleural fat.

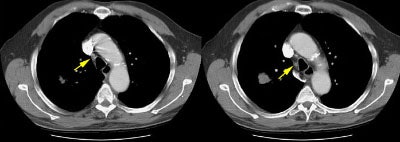

Example 2: In this patient with non-small cell lung cancer there is extension of the tumor between the ribs into the chest wall (yellow arrows). Disruption of the fat planes within the mediastinum (red arrows) is highly suggestive of mediastinal invasion as well. The lesion also abuts the main pulmonary artery.

CT findings which suggest mediastinal invasion include [8,51,55]:

1) Greater than 3 cm of contact

between

the mass and the mediastinum

2) Loss of the mediastinal fat plane

between the mass and vital structures

3) Greater than 90 degrees of contact

between the mass and the aorta or pericardium (with the total

aortic or

cardiac circumference of 360 degrees)

4) Mass effect or deformity of the

mediastinal structure or vessel

5) Pleural and/or pericardial

thickening

Both CT and MR have limitations in

distinguishing contiguity from tumor extension into specific

mediastinal structures [122]. Reported sensitivities for

detecting

mediastinal invasion by CT are 40% to 90%, specificities are 20%

to

90%, and accuracy is 56-89% [52,55,164]. For MR, the reported

sensitivity is 59-90%, specificity is 75-87%, and accuracy is

50-93%-

which is similar to CT [164].

Example 1: In this case of squamous cell carcinoma, the lesion had over 3 cm of contact with the mediastinum and there was focal loss of a clear fascial plane between the lesion and the aorta (left image). The lesion subtended an arch of less than 90 degrees of contact with the aorta (i.e., the lesion failed to meet criteria #3 above). At histopathologic analysis the lesion extended to the visceral pleura but did not involve the pleural surface or mediastinum.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

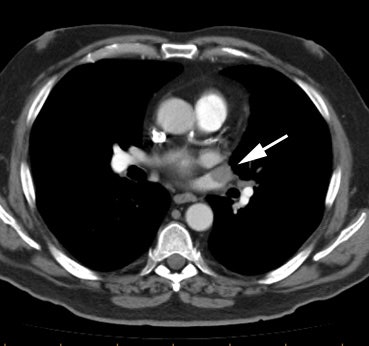

Example 2: This patient with non-small cell lung cancer demonstrates many findings which are suspicious for mediastinal invasion. There is greater than 3 cm of contact between the mass and the mediastinum, loss of the mediastinal fat plane between the mass and the left pulmonary artery, deformity of the left pulmonary artery, and pericardial thickening (yellow arrows). The patient also demonstrates contralateral mediastinal adenopathy (N3 nodes -- white arrow), subcarinal adenopathy (SC), and bilateral pleural effusions.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Other Methods to Determine Invasion

Iatrogenic pneumothorax: Iatrogenically created pneumothorax has been used to increase the accuracy of computed tomography for chest wall and mediastinal invasion. The presence of an air space between the mass and adjacent structures indicates that there is no invasion. The presence of benign pleural adhesions, however, can produce false-positive results. Tumors around the root of the pulmonary artery or vein may also be difficult to evaluate [52].

For chest wall invasion, reported sensitivity of iatrogenic pneumothorax is 100%, specificity is 80% to 100%, and accuracy is 88% to 100% [51,52]. For mediastinal invasion sensitivity is 100%, specificity is 57%, and accuracy is 76% [52]. Potential complications include pneumothorax (in up to 9% of cases). Patients with markedly impaired pulmonary function may not be candidates for this procedure because they may not be able to clinically tolerate even a small pneumothorax. [51,52]

Ultrasound: Sonography has

also

been used to assess for the presence of chest wall invasion.

Findings

which suggest invasion include disruption of the pleura,

extension

through the chest wall, and tumor fixation during respiration.

Reported

sensitivity was 100% (confidence interval 82-100%), specificity

98%

(confidence interval 92-99%), and accuracy 98%. Limitations of

the exam

include acoustic shadowing from adjacent ribs or vertebral

bodies which

can obscure some lesions and lack of sensitivity for lesions in

the

lung apices due to the lack of significant respiratory excursion

compared to the lung bases. [56]

Examples of iatrogenic pneumothorax

Example 1: In this case the patient had a large left upper lobe adenocarcinoma which was abutting the pleural surface on CT (Click here to view the patients CT scan). During percutaneous biopsy of the lesion, the patient developed a pneumothorax (white arrows) and the lesion could be seen to fall away from the lung apex indicating that there was no chest wall invasion. Although not intentional, a post-procedure pneumothorax can sometimes provide useful information.

|

NOTE: Click directly on either image below to enlarge. |

|

|

|

|

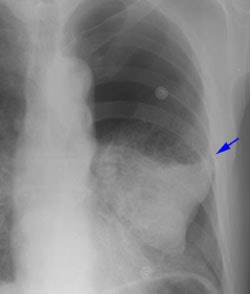

Example 2: This patient had a large peripheral squamous cell carcinoma that had a long area of contact with the chest wall on CT (Click here to view the patients CT scan). Following percutaneous biopsy of the mass the patient developed a large left pneumothorax. Although the left upper lobe collapsed, it did not completely fall away from the chest wall (blue arrow) increasing the concern for chest wall invasion in this case. At surgery, visceral pleural invasion was found, but there were only fibrous adhesions between the visceral pleura and the chest wall. There was no parietal pleura or chest wall invasion. Benign pleural adhesions are a cause of false-positive results when assessing for chest wall invasion with iatrogenic pneumothorax.

|

NOTE: Click directly on either image below to enlarge. |

|

|

|

|

Malignant pleural effusion:

Establishing the presence of a malignant pleural effusion can be difficult [164]. Cytologic evaluation is positive in only about two-thirds of cases [160]. A lesion may still be considered clinically T4 if the suspicion is high that an associated effusion is malignant [164]. One area in which FDG PET imaging is superior to CT scanning is in confirming the presence of a malignant effusion [131,154].The finding of increased FDG uptake greater than mediastinal blood pool activity that conforms to the pleural cavity is highly suggestive of a malignant effusion with a sensitivitiy of up to 100% and an accuracy, of 80% to 92% [153,154,164]. The accuracy is slightly decreased as inflammatory or infectious pleural fluid collections can also demonstrate increased FDG accumulation [154,159].

Invasion of other vital structures:

Obliteration of the central pulmonary veins by the tumor, especially the upper pulmonary veins, is highly suggestive of intrapericardial tumor extension. Although this does not necessarily predict non-resectability, prior knowledge of this finding will aid the surgeon in pre-operative planning [105].

|

Tumor extension into left atrium: The patient below had a large central left lung tumor. Tumor extension via the superior pulmonary vein into the left atrium can be seen (white arrows). |

|

|

Synchronous lesions:

A higher prevalence of synchronous lesions in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma has been reported recently and is most likely related to advances in radiologic imaging. The lack of respiratory motion with helical CT and the ability to perform thin slice image reconstructions has no doubt enhanced our ability to locate small lesions that would have not previously been detected. Aggressive surgical management of patients with bronchogenic carcinoma that are found to have synchronous lesions has been advocated in an effort to improve patient survival [98]. More data and controlled clinical studies will be necessary prior to drawing firm conclusions.

Extrathoracic Metastases in Bronchogenic Carcinoma: M1b

Although heavily affected by local practice, radiologic evaluation of the patient with NSCLC should attempt to provide accurate determination of local disease and a search for distant metastases [28]. Extrathoracic metastases occur in up to 30% of patients presenting with bronchogenic carcinoma [57] and CT can provide important information regarding the presence of unsuspected extrathoracic metastases. Such information prevents unnecessary thoracotomy in patients who would not benefit from this procedure. Generally, the higher the T or N stage, the more likely the patient will be to have extrathoracic metastases. However, up to 24% of patients with T1 lesions have extrathoracic metastases- either at the time of diagnosis (13%) or at 1 year followup (11%) [157]. Additionally, up to 25% of patients with normal sized intrathoracic lymph nodes on computed tomography can demonstrate extrathoracic metastases [19]. The risk for extrathoracic metastases is greatest in patients with adenocarcinoma or large cell carcinoma, and the likelihood of metastases in these patients does not necessary correlate with T or N stage [19,57]. Other features which would suggest an increased likelihood for metastases include a solid lesion (as opposed to ground-glass), spiculated lesion margins, and bronchovascular bundle thickening in the surrounding lung [157]. If these features are present, a more extensive workup for metastases may be required [157]. Common sites of extrathoracic metastases include the brain, adrenal, bone, and liver [19,57]. Unfortunately, CT will also detect benign lesions which are not readily distinguishable from pathologic lesions [31], and some have questioned whether preoperative evaluation for the presence of metastatic disease in clinically asymptomatic patients affects overall survival [58].

Adrenal:

Lung cancer has usually been

identified as

the most common malignancy to metastasize to the adrenal glands

and it

may be the only site of metastatic disease [109]. Adrenal

lesions can

be detected in between 2% to 10% of patients with bronchogenic

carcinoma [31,59], and more than 50% of these lesions will

prove

to be benign [59]. As a result, it has been stated that in

patients

with NSCLC an isolated adrenal mass is more likely benign than a

metastasis [59]. The reported incidence of adrenal metastases in

patients with bronchogenic carcinoma ranges from 2.4% to 7.5%

[31,57,59]. Nonetheless, a majority of community hospitals in

the

United States (70%) routinely scan through the adrenal glands

during CT

staging of patients with bronchogenic carcinoma [60]. Adrenal

masses

are best characterized on non-contrast CT examinations- as a

consequence, some authors recommend only non-contrast thoacic

CT

continued through the adrenal glands [114] or a non-contrast

scan of

the adrenals prior to performing a contrast enhanced staging

exam in

patients with bronchogenic carcinoma [109].

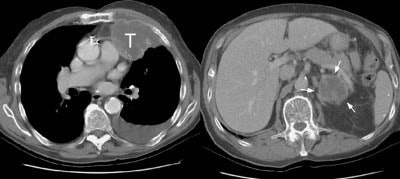

Example 1: This patient with non-small-cell lung cancer had a large necrotic primary tumor (T) and a large left adrenal metastasis (white arrows).

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

Example 2: In this patient with a T1N0 adenocarcinoma of the right lung, the staging CT scan revealed a heterogeneously enhancing mass in the left lobe of the liver (white arrows) and a low density mass in the left adrenal (yellow arrows). The liver lesion was subsequently shown to be an hemangioma and the adrenal lesion an adenoma. CT commonly detects other lesions which do not represent metastases, but which require further evaluation.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

.

Bone:

Bone metastases are present at

initial

presentation in up to 13% of NSCLC patients [160]. Any bone pain

or

elevation of alkaline phosphatase should be evaluated [6,57],

however,

up to 40% of lung cancer patients with proven bone metastases

can be

asymptomatic [161]. Nonetheless, in the absence of bone

symptoms,

pre-operative bone scinitgraphy is generally not useful. In the

absence

of symptoms, approximately 13% of scans are abnormal, but 94% of

these

are false-positive [6]. PET FDG imaging has been shown to have a

higher

sensitivity and specificity than bone scintigraphy in the

evaluation of

bone metastases [120].

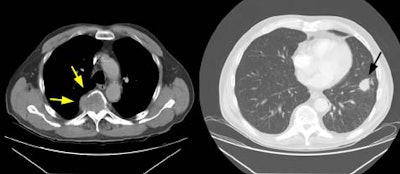

Example 1: The case below is an interesting example of a patient that presented with back pain and lower extremity weakness following a fall. A large soft tissue mass can be seen destroying the T5 vertebral body (yellow arrows). This proved to be metastatic non-small cell lung cancer from a 2.5 cm lesion (T1 by stage criteria) in the left lower lung (black arrow). There was no evidence of pathologic hilar or mediastinal adenopathy at CT. This patient is stage T1N0M1 (Stage IV).

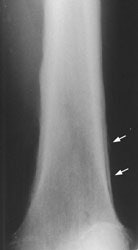

Example 2: This is an interesting case of a patient with non-small-cell lung cancer who complained of right shoulder pain. The bone scan demonstrates a bone lesion in the proximal right humerus (blue arrow) consistent with a metastasis. The scan also revealed linear uptake of tracer along the distal femurs and tibias bilaterally (black arrows). Uptake in the forearms was more irregular. A coned down plain film of the distal left femur demonstrated a solid periosteal reaction (white arrows). The findings are consistent with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy- a paraneoplastic condition seen in association with bronchogenic carcinoma.

NOTE: Click directly on the image to enlarge.

Brain:

The brain is a common site of

extrathoracic metastases [57,61]. The incidence of brain

metastases at

initial presentation in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma

generally

ranges from 10% to 13% [28,57,171], although higher and lower

values

have been reported [61,111,160,180]. The probability of

metastatic

disease to the brain from NSCLC correlates with the size of the

primary

tumor, the intrathoracic lymph node stage, and the tumor cell

type

[180]. Patients with adenocarcinoma or large cell carcinoma

appear to

be at an increased risk for cerebral metastases

[28,57,61,62,180].

Preoperative CT of the brain has been advocated in patients with

neurological symptoms and in patients with more advanced staged

disease

(stage III), adenocarcinoma, or large cell carcinoma regardless

of the

presence of symptoms [57,61]. It is important to note that

between 11%

to 21% of patients with brain metastases can be asymptomatic

[57,61]

and unsuspected brain metastases can occur in patients with

potentially

operable lung cancer (Stage I/II lesions) [110,111].

Pre-operative MRI

is more sensitive for the detection of brain lesions, but this

has not

been shown to inpart any increased survivial benefit [110,111].

PET FDG

imaging is less sensitive than conventional imaging modalities

for the

detection of brain metastases and is probably not useful in this

regards [120,171].

Example of brain metastases: This patient with non-small-cell lung cancer presented with left vocal cord paralysis. He did not have any neurological complaints. A central mass in the left lung was obstructing the left upper lobe bronchus (left image -- also note N2 subcarinal adenopathy). A head CT was requested by the patient's health care provider as part of the evaluation for his vocal cord paralysis and demonstrated multiple brain metastases, one of which is likely hemorrhagic (right fronto-parietal cortex).

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

.

Liver:

Routine scanning through the entire

liver

is controversial and not felt to be useful by some authors

[114].

However, hepatic metastases are seen in up to 12% of patients

with

bronchogenic carcinoma [57] and up to 61% of patients with liver

metastases do not have organ-specific indicators to suggest

their

presence [57]. Some authors recommend routine scanning of the

liver in

patients with bronchogenic carcinoma due to the relatively low

reliability of clinical indicators to suggest the presence of

hepatic

metastases [57]. Unfortunately, hepatic imaging will also result

in

detection of a substantial number of benign hepatic lesions. In

a study

of 1454 patients, Jones et al detected small (sized 1.5 cm or

less)

hepatic lesions in 17% of patients. Even in patients with an

underlying

malignancy (which formed 82% of the patients in the study group)

between 37% to 51% of the lesions were benign [63]. The

potential to

delay patient management, plus the additional cost of further

evaluation of detected lesions, must be weighed against the

significant

change in patient management should hepatic metastatic disease

be

identified. In a survey of community hospitals in the United

States,

only 30% of centers performed imaging through the entire liver

as part

of the staging evaluation of patients with bronchogenic

carcinoma

[60].

Example of Liver Metastases:

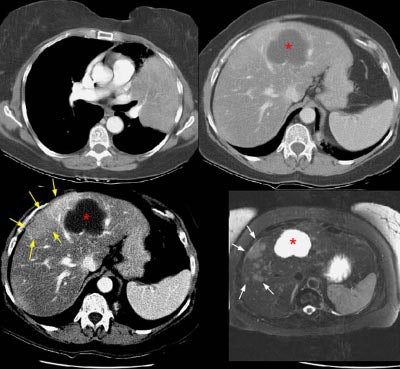

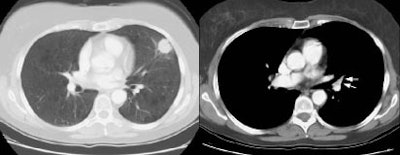

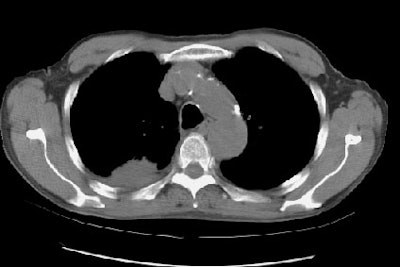

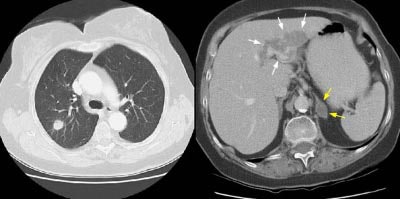

The patient below had an adenocarcinoma in the left lung that was obstructing the left upper lobe bronchus (left image upper row). The staging CT scan demonstrated a large liver cyst (*) and some underlying hepatic heterogeneity best appreciated on liver windows (yellow arrows). The patient had slightly elevated liver function tests, and the findings were felt to be most likely related to areas of sparing in a patient with some hepatic fatty infiltration. Because the possibility of metastatic disease could not be excluded, an MRI of the liver was performed. The heavily T2-weighed image shown (right image bottom row) revealed multiple liver metastases, many of which were not apparent on the contrast-enhanced CT scan (white arrows). MR imaging has been shown to be more sensitive for detecting liver metastases when compared to CT.

NOTE: Click image to enlarge

.