Carcinoid: (Neuroendocrine Lung Carcinoma)

View cases of carcinoid

Clinical:

The respiratory tract is the second most common location for carcinoid tumors (after the GI tract) accounting for 20-30% of carcinoids [16]. Although a rare tumor (1-2% of all lung tumors [6,16]), carcinoid is the most common pulmonary adenoma (75%). It is generally a low grade malignancy with a very good prognosis affecting men and women equally (although other authors indicate a male predominance [12]). Most patients present between 40-50 years of age. Carcinoids are the most common primary pulmonary neoplasm in children- usually occurring in late adolescence [7] and are the second most common primary pulmonary neoplasm in adults [14]. There is NO association between typical carcinoid tumors and smoking [3].

Symptoms include wheezing, recurrent pneumonia, and hemoptysis (up to 50% of cases due to vascular nature of the lesion). About 80-85% of the lesions are located centrally and are endobronchial (most commonly within the lobar bronchi [14]) and about 15-20% are located peripherally arising distal to the segmental bronchi. However, the larger studies describing a central predilection pre-date the widespread use of MDCT and peripheral lesions may be more common than previously thought [14]. Lesions that arise in the periphery are frequently atypical carcinoid tumors which are much more aggressive and frequently metastasize (most commonly to local nodes (48%), but the tumor produces characteristic osteoblastic bone mets). Atypical tumors are also more likely to invade vascular structures. Treatment for carcinoids is surgical resection- well differentiated tumors can be treated with conservative sleeve resection, wedge resection, or segmental resection sparing as much of the normal lung tissue as possible [10].

Carcinoid tumors are part of a spectrum of malignant neoplasms with neuroendocrine differentiation along with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and small cell carcinoma [6,7]. Carcinoid tumors arise from the duct epithelium (Kultschitzky cell) of bronchial mucus glands and can grow endo- or exobronchial. Kulchitsky cells contain neurosecretory granules and are capable of producing seratonin, ACTH, and bradykinin. Systemic hormonal manifestations are rare. Pulmonary carcinoids are uncommonly associated with carcinoid syndrome (2-5% of cases) and it is virtually always associated with advanced metastatic disease to the liver. Cushing syndrome occurs in about 2% of cases due to ectopic ACTH production [9,16]. Less than 5% of patients will have concurrent GI carcinoid.

Carcinoids are classified as Kulchitsky cell carcinomas. The most useful immunohistochemical markers for identifying neuroendocrine neoplasms are chromogranin, CD56, and synaptophysin [16]. The prognosis and behavioral features deteriorate according to the listed order below [7]:

Type I: This is the most common bronchial carcinoid accounting for 80-90% of cases [17]. The lesion can occur over a wide range of ages, with the average age of 46 years, and there is a roughly equal gender distribution [16]. Caucasians are predominantly affected [16]. Classic or "typical carcinoid" are generally central (within a bronchus), slow growing, with an excellent prognosis after resection. However, recent reports document increasing detection of peripheral carcinoid tumors (likely related to widespread CT use) [16]. On histopathologic analysis typical carinoids show no evidence of necrosis and less than 2 mitoses per high powered field (HPF) [7]. The 10 year survival rate is 82-84% [16]. Lymph node metastases are found in less than 5% of patients (up to 13% in another article [16])- and even if present, patients with lymph node metastases still have a relatively good prognosis [6].

Type II: Atypical carcinoids constitute approximately 10-25% of carcinoid tumors. The tumor is more common in men (2:1) and there is an association with smoking [7]. These lesions have higher mitotic activity (2-10 mitoses per HPF) and/or contain areas of necrosis [6,7]. Lesions with atypical histologic features have a much higher malignant potential and a higher rate of local and regional recurrence [5]. Lymph node metastases occur in about 57% of patients [16]. Findings associated with a worse prognosis include lymph node or distant metastases, older age at presentation, and higher number of mitoses [16]. Patients with atypical carcinoid tumors and regional lymph node metastases have a high likelihood for developing systemic metastases and have a significantly worse prognosis [6]. Overall, lymph node metastases are most strongly associated with decreased survival rates [16]. Treatment is surgical resection with systematic regional and mediastinal lymph node dissection [3]. Adjuvant chemotherapy is used in patients with systemic metastases [3]. Patients with atypical lesions have a lower survival rate- the 10 year survival rate is 24-50% [1,3].

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: LCNEC is a high grade non-small cell lung cancer with more than 10 mitoses per HPF [16]. These tumors are commonly positive for thyroid tanscription factor (TTF)-1 (41-75% of cases) and display high Ki-67 proliferation index (50-100%) [16]. Most patients are male (up to 95% of cases), with a history of heavy smoking, and a mean age of 65 years [16]. The lesion is indistinguishable from other lung cancers [16]. Calcification is seen in less than 9% of cases [16]. Pleural effusion can be seen in up to 24% of cases [16]. Prognosis is generally poor with a 5 year survival of 15-57% [16].

Type III: Small cell lung carcinoma

It has been recommended that carcinoid tumors should be staged using the standard lung cancer TNM staging system [11,13]. The estimated 5-year survival rates are 93% stage I, 85% stage II, 75% stage III, and 57% stage IV [13].

A new classification system for pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors has been proposed by WHO with a 3-tiered grading system based on the Ki67 index: G1- Ki67< 4%, no necrosis; G2- Ki67 4-25% and necrosis in fewer than 10 high power fields; and G3- Ki67> 25% and necrosis in more than 10 HPF [17].Pulmonary neuroendocrine proliferations:

Neuroendocrine (Kulchitsky) cells occur normaly in the mucosal epithelium of the respiratory tract and have the ability to synthesize, store, and secrete chemicals such as neuroamines and neuropeptides [16]. Three manifestations of pulmonary neuroendothelial cell proliferations have been described:

1- Reactive neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia with associated lung disease [16]: This is considered a response to chronic hypoxia and lung injury [16]. It can be seen in patients with chronic bronchitis or emphysema [16]. The condition is not considered preinvasive [16].

2- Proliferations associated with carcinoid tumor [16]: The presence of multiple carcinoid tumors and tumorlets (tumerlets are pulmonary neuroendocrine cell aggregates that measure less than or equal to 5mm and invade the adjacent basement membrane) has been referred to as pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia [15,16]. The condition is more common in women (85-93% of cases) and can cause Cushings syndrome [15]. About one-third of affected patient with have one dominant carcinoiod tumor [15]. The prognosis is very good, with the lesions generally demonstrating very slow growth over time [15].

3- Diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: The WHO classification applies the term "diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH)" to a generalized proliferation of scattered single cells, small nodules, or linear proliferations of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells that may be confined to the bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium that does not extend beyond the basement membrane [15,16,19]. However, the condition if often accompanied by nodules that extend beyond the basement membrane or the airway wall and these local extralumenal proliferaitons are termed tumorlets when smaller than 5 mm and carcinoid tumors if larger than 5 mm [15,16,19]. The condition is considered a preinvasive (preneoplastic) lesion that may give rise to carcinoid tumors [15,16,19]. Patients with DIPNECH are typically/almost exclusively middle aged to elderly women (50-70 years) who may be asymptomatic (up to half of patients are asymptomatic) or may present with indolent chronic respiratory symptoms (non-productive cough or dyspnea) [16,19].

Patients are usually managed conservatively and their prognsis is generally good with a 5-year survival of 83% [16]. The condition manifests as multifocal bilateral pulmonary micronodules with a lower lobe and peribronchiolar predominance [16,19]. The small nodules have a centrilobular distribution centered on small airways [19].There is also bronchial wall thickening, which can be nodular or beaded [19]. Expiratory HRCT images will characteristically show mosaic attenuation with evidence of air trapping secondary to a constrictive bronchiolitis which is related to peribronchiolar fibrosis that occurs secondary to peptides secreted by the neuroendocrine cells [16,19].

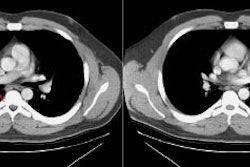

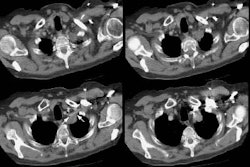

| Multiple carcinoids and tumorlets: The

patient shown below had a history of breast cancer and

presented with multiple, slowly enlarging lung nodules. A

dominant nodules was seen in the lingula, with multiple

other, scattered nodules that measured less than 1 cm. On

resection, the patient was found to have multiple pulmonary

carcinoids and tumorlets. |

|

X-ray:

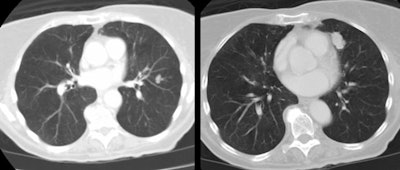

Because of their central location, the most common radiographic finding is a central mass with atelectasis or consolidation. CT will demonstrate an endobronchial mass; atelectasis or consolidation may be seen distally. Intratumoral calcification is seen in 25-30% of typical carcinoids and is usually eccentric [7]. Diffuse calcification has been reported due to ossifying elements within the tumor [3,7]. The lesion may cause splaying of the bronchi without destruction. Because of its vascularity, it usually demonstrates marked, homogeneous contrast enhancement [7]- however, not all carcinoids will enhance [3]. If peripheral, the lesion appears as an SPN. Cavitation has not been reported in carcinoid tumors [3].

Carcinoids are bright on T2 or STIR images and cannot be

differentiated from other neoplasms [2].

Scintigraphy with octreotide has been used to assess for the

primary lesion and metastatic disease [3]. Carcinoid tumors

producing adenocorticotropic hormone have high numbers of

somatostatin recepotrs, thus enabling detection with octreotide

[12].

Carcinoid tumors may not demonstrate increased activity on PET FDG exams [3,4]. Although some feel that PET imaging is not a useful test for the evaluation of carcinoid tumors [3], sensitivities of up to 75% have been reported (particularly for lesions presenting as solitary pulmonary nodules) [8]. Atypical carcinoids are somewhat more likely to be PET positive [8].

PET imaging with 68Ga-DOTA-peptides has demonstrated

a better detection rate than FDG PET (79% vs 55%) [18].

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiology 1995; Carcinoid tumors of the lung: Do atypical features require aggressive management? 197 (2): 555-556 (No abstract available)

(2) J Thorac Imag 1995, The bronchi: An imaging perspective. 10: 236-254 (p.243-244)

(3) Radiographics 1999; Rosado de Christenson ML, et al. Thoracic carcinoids: Radiologic-Pathologic correlation. From the archives of the AFIP. 19: 707-736

(4) AJR 1998; Erasmus JJ, et al. Evaluation of primary pulmonary carcinoid tumors using FDG PET. 170: 1369-1373

(5) Radiology 1998; Gould PM, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: Importance of prognostic factors tha influence patterns of recurrence and overall survival. 208: 181-185

(6) Chest 2001; Thomas CF, et al. Typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Outcome in patients presenting with regional lymph node involvement. 119: 1143-1150

(7) Radiographics 2006; Chong S, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: clinical, pathologic, and imaging findings. 26: 41-58

(8) Chest 2007; Daniels CE, et al. The utility of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the evaluation of carcinoid tumors presenting as pulmonary nodules. 131: 255-260

(9) Radiographics 2007; Scarsbrook AF, et al. Anatomic and functional imaging of metastatic carcinoid tumors. 27: 455-476

(10) J Nucl Med 2009; Kayani I, et al. A comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE and 18F-FDG PET/CT in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. 50: 1927-1932

(11) AJR 2010; Kligerman S, Abbott G. A radiologic review of the new TNM classification for lung cancer. 194: 562-573

(12) AJR 2010; Koo CW, et al. Spectrum of pulmonary neuroendocrine cell proliferation: diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia, tumorlet, and carcinoids. 195: 661-668

(13) Radiographics 2010; UyBico SJ, et al. Lung cancer staging

essentials: the new TNM staging system and potential imaging

pitfalls. 30: 1163-1181

(14) AJR 2011; Messinger QC, et al. CT features of peripheral

pulmonary carcinoiod tumors. 197: 1073-1080

(15) Chest 2007; Aubry MC, et al. Significance of multiple

carcinoid tumors and tumorlets in surgica lung specimens. 131:

1635-1643

(16) Radiographics 2013; Benson REC, et al. Spectrum of pulmonary

neuroendocrine proliferations and neoplasms. 33: 1631-1649

(17) J Nucl Med 2017; Bodei L, et al. Current concepts in 68Ga-DOTATATE

imaging of neuroendocrine neoplasms: interpretation,

biodistribution, dosimetry, and molecular strategies. 58:

1718-1726

(18) J Nucl Med 2018; Sanli Y, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor

diagnosis and management: 68Ga-DOTATE PET/CT. 211:

267-277

(19) AJR 2020; Little BP, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary

neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: imaging and clinical features of

a frequently delayed diagnosis. 215: 1312-1320