Arteriovenous Malformation:

View cases of pulmonary AVM's

Clinical:

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (AVM's) are multiple in 30-50% of cases, and bilateral in 10% of cases. Patients with pulmonary AVM's are mostly asymptomatic, but can present with dyspnea (due to left-to-right shunting), hemoptysis, clubbing, polycythemia, or cyanosis. Because most pulmonary AVM's are located in the lung bases (65-70% of lesions), the left to right shunting that occurs is larger when the patient is sitting or standing, than when supine. This phenomenon is termed "orthodeoxia" and can be demonstrated by obtaining arterial blood gas measurements in supine and standing (or sitting) position [5]. The natural course of the lesion is not benign- paradoxical emboli can also occur and result in cerebral infarction (up to 50% of patients and can be subclinical) or cerebral abscess (5-14% of patients [5,7]). Massive hemoptysis can occur in up to 8% of patients. Pregnant patients are at increased risk for AVM's rupture and hemoptysis during delivery [7]. In patients with pulmonary AVM's, mortality can be as high as 11% if untreated [5].

Pulmonary AVM's are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic

telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendau syndrome, also known as

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia) in one third of patients

with a solitary lesion (other authors suggest that between 65-90%

of patients with a solitary pulmonary AVM have HHT [13]), and in

over 50% of patients with multiple AVM's. HHT is a hereditary

disorder (autosomal dominant [chromosome 9 mutations account for

75% of cases]) caused by at least three mutations- ENG (type I

HHT) encoding endoglon; ACVRL1 (type II HHT) encoding activin

receptorlike kinase 1 (ALK-1); and SMAD4 which is associated with

juvenile polyposis [17]. HHT is characterized by a general

vascular dysplasia with AVM's/telangiectasias of multiple organs

including the nose (causing recurrent epistaxis in about 90% of

adult patients), CNS (about 10% of HHT patients have cerebral

AVM's [13]), liver (as many as 60% of HHT patients have hepatic

AVM's [13]), GI tract, and lungs. Telangiectasias often do not

appear until the 3rd decade of life. Approximately 5-30% (up to

50% [13]) of HHT patients have pulmonary AVM's [5,10] and there is

usually a family history of pulmonary AVM's in these patients. HHT

is diagnosed according to the Curacao criteria which include

multiple mucocutaneous telangiectasias, epistaxis, visceral

arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), and a family history of HHT in

a first degree relative [17].

Pulmonary AVM's can be classified as simple- a single feeding artery or draining vein, or complex- multiple feeding arteries. Simple lesions account for 80-90% of cases [5,13]. Very slow growth over time may be observed [13]. It has been suggested that growth occurs most during pregnancy and puberty- possibly reflecting hormonal influences [13].

All lesions with feeding arteries larger than 3 mm should be embolized due to the risk of paradoxical embolism [7,8]. Recent guidelines now also acknowledge that treatment of AvM's with feeders small than 3 mm is also appropriate as paradoxical emboli can also occur in these patients [13,15]. Particulate agents should not be used because of the obvious risk of systemic embolization [5]. Stainless steel coils or silicon or latex balloons are commonly used [5]. The reported risk of paradoxical coil embolization ranges from 2-4% (particularly when the communication is large with a high degree of flow) [11]. When treating the lesions with coil embolization, it is essential to thrombose all of the feeding arteries, as recurrence is usually secondary to enlargement of a secondary feeder that was missed at the time of embolization.

Recanalization has been reported to occur infrequently

(approximately 4-15% of cases), but the actual rate of

recanalization may be as high as 25-57%. Risk factors for failed

embolization with recanalization include large diameter of feeding

arteries, occlusion with fewer coils, use of oversized coils, and

proximal placement of coils in the feeding artery more than 1 cm

from the sac [11,12]. Increased detection of recanalization can be

accomplished with contrast enhanced CT scans which demonstrate

lesion enhancement, rather than non-contrast studies which assess

for lesion enlargement only [4]. Other authors have subclassified

recurrent lesions as 'recanalization' if there is persistent flow

through a previously placed coil nest and 'reperfusion' if there

is persistence of flow through small feeders from adjacent normal

pulmonary arteries or incomplete initial treatment [14].

Recanalization is the most common etiology for a recurrent or

persistent AVMs, but recanalization and reperfusion can coexist

[14]. Smoking is associated with AVM persistence in patients with

HHT [16].

Repeat embolization can be performed for lesions that recanalize

[5]. The combined use of coils and Amplatzer vascular plugs has

been reported to decrease the risk for recanalization [12,13].

Pulmonary AVMs with a feeding vessel smaller than 3 mm can be

treated with microvascular plugs (a detachable and re-sheathable

embolic device composed of a self expanding nitinol cage partially

coated with polytetrafluoroethylene) with a low persistence rate

of about 6% one year after treatment [15]. Coils are less

effective for treating small feeding vessel AVMs with a

persistence rate of up to 21%, and the risk for persistence is

directly correlated with the coil nest-to-sac distance [15].

Amplatzer type plugs (4-8mm) can provide occlusion with only one

plug per feeding artery with a low persistence rate, but are not

compatible with microcatheters [15].

Complications of embolization therapy include systemic embolization of the coil or balloon (2.5 to 6% of cases, pulmonary infarction due to occlusion of vessels to normal lung, and peri-catheter thrombosis [5]. Abnormally enlarged systemic arteries can be identified in up to 40% of patients on followup after embolization [9]. This is possibly related to post-procedural local ischemia and it occurs more frequently in patients with evidence of infarction following treatment [9].

X-ray:

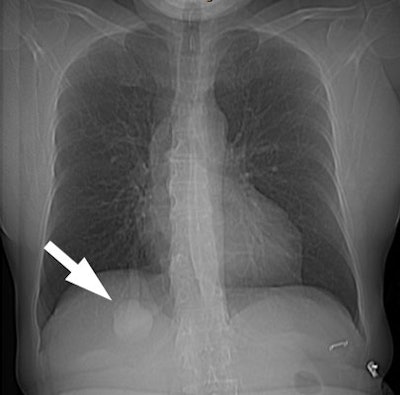

On plain films, AVM's generally appear as a solitary or multiple

pulmonary nodules. Classically one should be able to identify the

enlarged vessel entering the lesion. The lesion will be noted to

change size with inspiration and expiration, or supine versus

erect films.

| The patient shown below had a

large right lower lobe AVM (white arrow). Note the large

vessel extending to the lesion. |

|

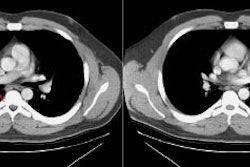

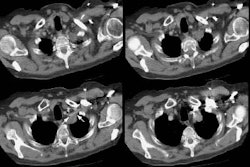

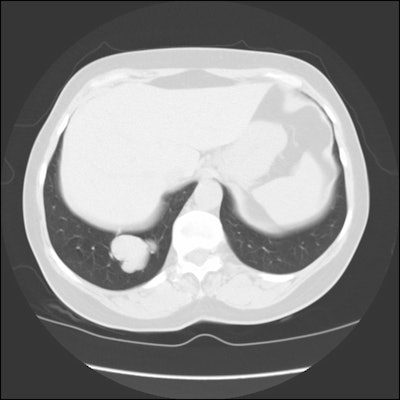

CT and helical CT can also be used to demonstrate the presence of

a feeding artery. Most of these lesions have a single feeding

artery and draining vein, however, they may be multiple. Spiral CT

with contiguous images and overlapping reconstructions is more

sensitive than angiography for detecting and displaying the

vascular connections of pulmonary AVM's- the angio-architecture

can be identified in 76 to 95% of lesions [5]. Contrast

enhancement of the lesion may not be seen if the lesion is

thrombosed.

| CT from the patient shown

above: Click image to view cine file. |

|

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiology 1994; White RI Jr, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: diagnosis with three-dimensional helical CT-a breakthrough without contrast media. 191(3), 613-614 (No abstract available)

(3) Radiology 1997; Sum and Substance: Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasis. 204: 342 (No abstract available)

(4) AJR 1998; Sagara K, et al. Recanalization after coil embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Study of long-term outcome and mechanism of recanalization. 170: 727-730

(5) J Thorac Imaging 1998; Najarian KE, et al. Arterial embolization in the chest. 13: 93-104

(6) AJR 2000; Gamboa P, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM): Paradoxical embolism through the arteriovenous fistula can cause brain abscess and infarct. 175: 857-858

(7) Radiology 2002; Dinkel HP, Triller J. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: embolotherapy with superselective coaxial catheter placement and filling of venous sac with guglielmi detachable coils. 223: 709-714

(8) Radiology 2006; Remy-Jardin M, et al. Pulmonary ateriovenous malformations treated with embolotherapy: helical CT evaluation of long-term effectiveness after 2-21 year followup. 239: 576-585

(9) Radiology 2007; Brillet PY, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation treated with embolotherapy: systemic collateral supply at multidetector C angiography after 2-20 year followup. 242: 267-276

(10) AJR 2008; Schneider G, et al. MR angiography for detection of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. 190: 892-901

(11) AJR 2009; Abdel Aal AK, et al. Occlusion time for amplatzer vascular plug in the management of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. 192: 793-799

(12) AJR 2010; Trerotola SO, Pyeritz RE. Does use of coils in addition to amplatzer vascular plugs prevent recancalization? 195: 766-771

(13) AJR 2010; Trerotola SO, Pyeritz RE. PAVM embolization: an

update. 195: 837-845

(14) AJR 2013; Woodward CS, et al. Treated pulmonary

arteriovenous malformations: patterns of persistence and

associated retreatment success. 269: 919-926

(15) AJR 2018; Mahdjoub E, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous

malformations: safety and efficacy of microvascular plugs. 211:

1135-1143

(16) Radiology 2019; Haddad MM, et al. Smoking significantly

impacts persistence rates in embolized pulmonary arteriovenous

malformations in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic

telangiectasia. 292: 762-770

(17) AJR 2020; Shin SM, et al. CT angiography findings of

pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in children and young adults

with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. 214: 1369-1376