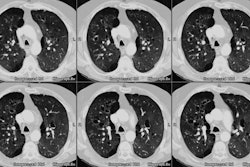

Pneumothorax/ Spontaneous Pneumothorax:

View cases of pneumothorax

Clinical:

Although many pneumothoraces will resorb on their own, the identification of pneumothorax can have important clinical implications. Even a small pneumothorax can progress to a tension pneumothorax in which the intrapleural pressure exceeds pressure in the lung- this can compromise systemic venous return and reduce cardiac output. Significant respiratory effects may also be experienced by patients with marginal pulmonary function. Therefore, the decision to intervene with chest tube placement should be based upon the patients clinical status, in combination with the radiologic findings. Although tension is a clinical diagnosis, it may be suggested on CXR when there is mediastinal shift to the contralateral side, flattening or inversion of the ipsilateral diaphragm, and hyperexpanded ipsilateral chest [11].

Patients with pneumothorax generally complain of dyspnea and ipsilateral pleuritic pain that radiates to the back and shoulder. As the volume of the affected lung is reduced, the size of the rupture in the visceral pleura decreases and spontaneous closure is not uncommon in patients without underlying lung disease. The pneumothorax resorbs at a rate of 1.25% per day, but this rate can be accelerated by increasing the inspired oxygen concentration which will lower the partial pressure of nitrogen in the tissues. [1] Patients with small, stable pneumothoraces can be managed with bed rest and supplemental oxygen. Indications for chest tube placement include any sized pneumothorax that produces dyspnea or chest pain, an enlarging pneumothorax, or a pneumothorax that exceeds 25% of the volume of one hemithorax [7]. Spontaneous pneumothorax can occur as a result of:

1- Bleb disease: Bleb disease is the most common cause of spontaneous pneumothorax in young adults (20-40y). A bleb is a collection of air contained within the elastic fibers of the visceral pleura. Blebs likely form as a result from subpleural alveolar rupture. Males are affected more than females (3:1) and individuals tend to be tall and thin. Blebs occur in the visceral pleura predominantly in the upper lobes/apical regions (possibly secondary to ischemic changes). Recurrent episodes occur in 30% of patients and usually involve the same side. Most patients (90%) will respond to thoracostomy tube treatment with complete rexpansion. More aggressive treatment is needed if the air leak persists beyond seven days.

2- COPD: COPD is the most common pulmonary disorder associated with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax.

3- Asthma: Due to bronchiolar mucus plugging

4- Interstitial Lung Disease: Sarcoid, Eosinophilic granuloma, Tuberous sclerosis, Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

5- Subpleural mets: Osteosarcoma- in about 5% of cases, spontaneous pneumothorax develops in association with subpleural osteosarcoma metastases [2].

6- Catamenial: Pleural endometrial implants (endometriosis) result in recurrent pneumothoraces during menses [12]. Coexistent abdominal endometriosis is found in most patients (60-80% of cases) [12]. It is postulated that endometrial tissue implants along the underside of the diaphragm- most commonly the right side due to preferential peritoneal fluid circulation via the right paracolic gutter [12]. Fenestrations in the diaphragm develop as a result of cyclical necrosis of the endometrial tissue allowing spread to the pleural space [12]. Patients often present with right scapular or thoracic pain occuring from 24 hours before to 72 hours after the onset of menstruation [12]. A right sided pneumothorax is found in about 90% of patients [12]. Hormonal manipulation can be used to suppress the endometrial tissue or the dospits can be resected and the fenestrations closed via VATS [12].

7.- PCP infection with associated cystic changes. The overall incidence of pneumothorax in HIV patients with PCP infection approaches 10% and appears to be more frequent in patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine prophylaxis.

8- Iatrogenic: Mechanical ventilated patients have a 4 to 15% incidence of pneumothorax (higher in ARDS patients). High end-expiratory pressures, large tidal volumes, necrotizing infection, and obstructive airway disease increase the risk for pneumothorax in ventilated patients. Pneumothoraces in these patients tend to enlarge rapidly and become under tension. In a supine ICU patient, even a large pneumothorax may be difficult to detect. Air will collect anteromedially and appear as a relatively lucent area in the juxtacardiac region. Other findings include sharp visualization of the superior vena cava, left superior intercostal vein, or the superior pulmonary veins. Air may also accumulate sub-pulmonically within the lower hemithorax and extend down the costophrenic sulcus producing a "deep sulcus sign". Because of the stiffness of the lung parenchyma in ICU patients (particularly in ARDS patients) the typical findings of tension such as mediastinal shift and total lung collapse may be absent. Findings which suggest tension include flattening of the heart border, and displacement of the azygoesophageal recess or anterior junction line into the contralateral hemithorax.

9. Pneumothorax ex vacuo: A pneumothorax can be observed localized to the pleural space beyond a collapsed lobe. This finding is more frequently observed in children and preferentially involves the right upper lobe. The etiology is believed to be analogous to the vacuum phenomenon seen in joints. Gas (nitrogen from the adjacent tissues and blood) in the pleural space localizes to the area adjacent to the atelectasis while the seal between the visceral and parietal pleura of the middle and lower lobes remains intact. Treatment should be directed at the underlying bronchial abnormality, and not the pleural space- ie: the patient requires bronchoscopy and not a chest tube [3].

10. Trauma: Pneumothorax occurs in 15-40% of cases of blunt chest trauma [8,11]. About 70% of patients with pneumothorax as a result of blunt chest trauma will have associated rib fractures. CT is superior to plain films in the detection of pneumothorax- especially in supine trauma patients [8]. Between 10-15% of pneumothoraces from blunt trauma are not visualized on CXR, but can be seen on CT [11]. Very small anterior pneumothoraces detected incidentally in blunt trauma patients can be managed with observation if positive pressure ventilation will not be employed [9].

X-ray:

Both inspiratory and expiratory films are equally sensitive for the detection of pneumothorax. Inspiratory films are preferred as they produce less distortion of the underlying pulmonary parenchyma [4]. Upright CXR will demonstrate a thin, white, visceral pleural line separated from the parietal pleura by a radiolucent airspace. Pulmonary vessels extend to the visceral pleural line, but not beyond. Approximately 30% of pneumothoraces are undetected on supine radiographs [10]. Clues to the presence of a pnuemothorax on a supine film include the "deep sulcus sign" (an apparent deepening of the costophrenic angle produced by air in the caudal portion of the pleural space ) [10], the double diaphragm sign (two air-diaphragm interfaces are seen- one representing the interface between the ventral portion of the pneumothorax and the anterior diaphragm and the other the interface between the more dorsal portion of the pneumothorax and the posterior portion of the diaphragm), increased lucency at the lung base of the affected side, and visibility of pericardial fat tags. On an upright film, a 25% pneumothorax will produce an average separation of 2.2 cm from the lung margin to the chest wall. [5,6]

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiology 1997; Carroll AM. Sum & substance. 203: 368 (No abstract available)

(2) AJR 1997; Johnson GL, et al. Thoracic involvement from osteosarcoma: typical and atypical CT manifestations. 168: 347-349 (No abstract available)

(3) J Thorac Imag 1996; Atypical manifestations of pulmonary atelectasis. 11: 165-175 (p.171)

(4) AJR 1996; Feb 166(2): 313-316

(5) Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1996; Apr 17(2): 119-141

(6) ACR Syllabi #40; p14-17

(7) AJR 1995; Klein JS. Interventional radiology of the chest: Image-guided percutaneous drainage of pleural effusions, lung abscess, and pneumothorax. 164: 581-588

(8) Radiographics 1998; van Hise ML, et al. CT in blunt chest trauma: Indications and limitations. 18: 1071-1084

(9) AJR 1998; Wolfman NT, et al. Validity of CT classification on management of occult pneumothorax: A prospective study. 171: 1317-1320

(10) Radiology 2003; Kong A. The deep sulcus sign. 228: 415-416

(11) Radiographics 2008; Kaewlai R, et al. Multidetector CT of blunt

thoracic trauma. 28: 1555-1570

(12) Radiographics 2012; Walker CM, et al. Tumorlike conditions of the pleura. 32: 971-985