In December 2000, Canadian downhill skier Cary Mullen held a press conference to announce his retirement at age 31. He’d never competed in an Olympics, and had won only one World Cup event, at Aspen, CO, in 1994.

But double vision and headaches, and the fear of permanent brain damage, forced Mullen to retire. He had suffered three concussions in his career, including one from a stunning crash in 1997 that ended his hope of competing in the 1998 Olympics. After he landed a third concussion while skiing in France in 1999, it took nearly a year for Mullen's doctors to recommend that he end his career.

Mullen’s case is not unusual. Concussions are tricky business in the world of sports medicine. From a radiology standpoint, they are nearly impossible to diagnose. X-ray, CT, MRI -- historically, none has proven effective in diagnosing concussion, or in Mullen’s case, diagnosing their severity and lingering effects.

"The thing that we are talking about is a minor head injury," said Dr. Michael Fredericson, director of sports medicine clinics in the department of functional restoration at Stanford University in Stanford, CA. "If it’s bad enough, then it will show up on a scan. But usually in athletic injuries, these things don’t show up on a scan. It would have to be really obvious to show up on a scan."

Then again, maybe not. Dr. David Kushner, an assistant professor of neurology and neurorehabilitation at the University of Miami School of Medicine in Florida, has done several studies that show that imaging is not an effective way to diagnose a concussion.

In his most recent study, Kushner wrote that "with an uncomplicated brain concussion, limited structural axonal injury may be present but not evident on diagnostic computed tomography scanning or magnetic resonance imaging" (American Family Physician, September 15, 2001, Vol. 64:6, pp. 1007-1014).

Rather, other forms of neurological testing, like clinical examination, are far more reliable, Kushner and Fredericson said. Kushner added that an ideal situation would be to test an athlete or team of athletes before a season starts, and then repeat the same tests when an athlete suffers a head injury. In that situation, a doctor would be able to detect differences in responses or response times.

While imaging may not be effective in diagnosing concussions, it is effective in revealing other types of brain injuries.

"A brain CT scan is excellent for showing any neurosurgical injuries, like intracranial bleeding or contusions," Kushner said in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "For a concussion, generally, a CT scan would come up negative, but in the cases of winter sports (injuries) a brain CT scan should be done. Individuals who have brain contusions can evolve into additional bleeding. Sometimes you can have a negative brain scan, but symptoms persist, so you could use an MRI, which is more sensitive, so it would be more likely to show brain injuries like bleeding or contusions."

Kushner said that imaging is also ineffective when trying to determine how many concussions are too many. Many athletes, particularly in contact sports like hockey, suffer repetitive concussions over the course of a career.

In fact, the National Hockey League injury report for December 7, 2001, listed four players with concussions and one with post-concussion syndrome.

|

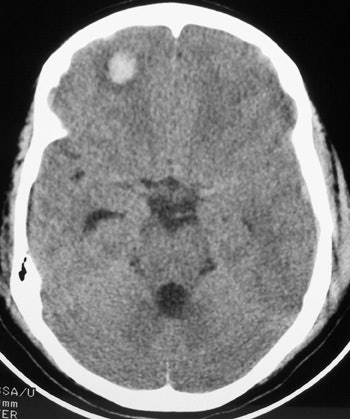

| The above illustrates an epidural hematoma in the posterior fossa (right), secondary to a fracture of the skull base. Epidural hematomas are typically due to arterial bleeding between the surface of the brain and the skull. However, in this case the fracture is adjacent to the transverse sinus and is likely due to venous bleeding. This can be seen following blunt trauma to the head. |

|

| The image above illustrates a right frontal lobe parenchymal hemorrhagic contusion. This represents bleeding in the brain and is commonly seen following blunt trauma to the head. |

|

| Here, the subdural hematoma (right) is due to venous bleeding on the surface of the brain. This results in a space-occupying lesion with mass effect, shifting brain tissue to the left. The subarachnoid hemorrhage is due to arterial bleeding within the meninges lining the surface of the brain. Both types of bleeding can be seen following blunt trauma to the head. Images courtesy of Dr. John Cameron, University of Miami. |

In the case of post-concussion syndrome, as in the skier Mullen’s case, neuropsychological testing is more effective in determining an athlete’s ability to return to his or her sport. In his study, Kushner noted that no athlete who had a loss of consciousness should return to practice or competition "until they have been asymptomatic at rest or with exertion for a minimum of one week."

It has been shown in many studies that repeated concussions increase an athlete’s risk for permanent brain damage or even death. Mullen said he had to "live his life like a 95-year-old man."

The struggle for a physician is determining when enough is enough.

"Imaging does not tell you very much in terms of when an individual is safe to go back," Kushner said. "You have to rely on clinical examinations, physical signs, complaints, and symptoms."

By Jill R. DorsonAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

February 21, 2002

Related Reading

Diffusion-weighted MRI useful in evaluating pediatric head trauma, October 3, 2001

Canadians follow the Masters path for head CT, May 29, 2001

Clinical decision rule guides CT management of patients with minor head injury, May 7, 2001

Clinical criteria may obviate CT, radiography in trauma patients, July 13, 2000

CT best first step for diagnosing subarachnoid hemorrhage, May 16, 2000

fMRI could be instrumental in long-term study of head trauma, December 2, 1999

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com